Words by Stella Rousham

In preparation for my interview with dance artist and choreographer Jules Cunningham last Saturday, I decided to listen to Stravinsky’s The Firebird and Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto, No.1 – two canonical classical pieces of music that inform Jules’ upcoming double-bill m/y-kovsky | fire bird at Sadler’s Wells next week.

Whilst I’ve typically perceived classical music as a symbol of prestige and elitism, speaking to Jules introduced a new lens through which to navigate this seemingly impenetrable genre. Reflecting on their own choreographic processes and artistic journey, Jules shared with me the intricate connections between the self, the everyday and personal experience that can be found within classical forms. Originally made in a pre-pandemic world, Jules further voiced the complexities of choreographic power and collaboration, that has come with bringing fire bird and m/y-kovksy to the stage this month.

SR: Would you be able to briefly introduce the two works: m/y-kovsky and fire bird.

JC: In November, I will be performing two shows. m/y-kovsky which was first made in 2019, and fire bird, made in 2020.

The m/y-kovsky piece is a quartet I made to the First Movement of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No.1. It was originally made for Art Night, which is like a visual art, mostly performance, platform that happens in London. I listen to a lot of classical music, like on the radio. I had definitely heard this piece of music before. But when I heard it in 2019, I really liked it. I started questioning: Why am I drawn to that music this moment? What is it about in me that needs to connect to this music in this moment in time? I wasn’t feeling very well at the time. It was sort of it this thing that I would go into listening and imagining. I started listening to it every day.

fire bird is a solo. I’ve been thinking about fire bird and the music for more than 10 years, before I even started to make things. Around 2012 I was dancing in Michael Clark Company in New York. They did this Stravinsky programme. At the beginning of the show there was a video projection of Stravinsky conducting the finale of The Firebird. I don’t think I should really say this, but the projection was the best part. All the rest of the show was great. But that really stuck with me. I guess I’ve always connected that music with that part of my life.

SR: I’d love to hear a bit more about the movement of the two pieces; did you have certain method or approach for devising the movement?

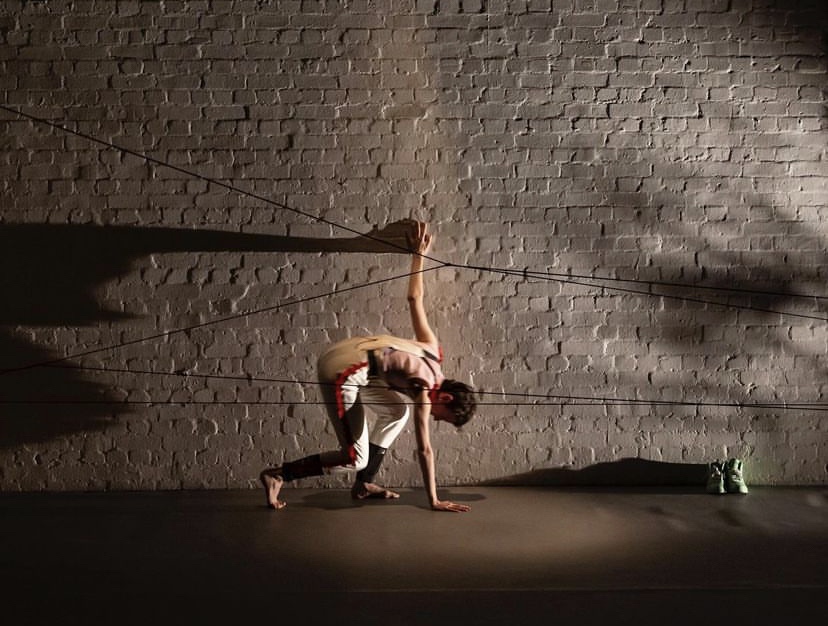

JC: fire bird is very much me. It’s all the movements I’ve ever done contained in my body. I think it was about finding where different parts of me could come out or the different ways that I move or want to move, can come out. The movement also came from times I’ve been asked to dance in ways that feel beyond me or I felt like I had to force it out. So I guess it’s also about sensation, things that can feel very internal or private.

It’s also related to my mental health. What movements or ways of being in yourself that you mask because it’s not socially acceptable. What are those impulses? How can that be in the work? The making process was actually quite mysterious. Often I would have no idea how a certain moment or movement had happened.

That was really different to m/y-kovsky. In this piece, it was actually very clear to me what the movement was as I went along. The Tchaikovsky is a massive orchestral piece; it’s really over the top.

With the actual process of making the dance, I made it really quickly. It’s quite dense. A lot of movements in it. The whole process felt like listening. I feel like the music told me what to do; I didn’t think ahead, it was really sequential. The sequences fit with different bits of the music, because the music is broken down into short sections, with a repetition of the earlier sections.

SR: How did it feel taking, as you said, very grand orchestral pieces of music and playing with them in this creative way; personalising and queering these really iconic, classical forms.

JC: People often feel that classical music can be really elitist. Oh, ‘it’s not for me’, it’s ‘intellectual’ or ‘posh’ or whatever. When you listen to Tchaikovsky or Stravinsky, there’s sounds in them that are relatable to sounds that we hear all the time. Especially in London, there’s a lot of construction – drilling, banging and traffic. We just think of them as like nuisance and sound pollution. But if you expand what music is, it’s really all the sounds like that, which we hear every day.

I work with a person called Joyce Henderson, who has worked with Complicite for a really long time. We’ve thought a lot about a way of being, thinking and listening that doesn’t separate the technical or structural aspects of dance or music from everyday experience.

I guess I can also explain the title of the piece, m/y-kovsky. The work I made before m/y-kovsky was a piece I made called m/y. This title comes from this book called The Lesbian Body by Monique Wittig. When I was making the quartet, that book was very much still in my head. Also, because it rhymes with Tchaikovsky, I think it might have been a bit of a joke – bringing the ‘my’ into the Tchaikovsky music. The m/y is also about breaking open the self and magnifying it.

“People often feel that classical music can be really elitist, but there’s sounds in the music that are relatable to sounds that we hear all the time.” ~ Jules Cunningham.

SR: Originally, m/y-kovsky and fire bird were made and performed separately. Now, at Sadler’s Wells, they’re going to be performed alongside each other. Does that feel different?

JC: I’ve yet to find out. I think it’ll work! Especially with the help of the people who work with me closely. I also think you have an instinct that it’ll be okay. They’re both really different pieces, really different worlds. Maybe there is a connection through the classical music.

When I’m performing them now, I’m thinking a lot about the time I first made them, which was before the pandemic. Where was I and what I was thinking about at that time? But also, where am I now doing them again? The whole the world is different, I’m different. I’m working with different dancers and not dancing in m/y-kovsky this time. This is first time that I’ve not been in a work that I’ve made. It feels actually really nice to see it from the outside, I feel like I can do a bit more work with it. But also I find it more stressful to not be in.

SR: I guess because there’s so much more you can see?

JC: And I think with nervousness, at least if you dance, you sort of get through it. But if you’re not….there’s a lot more going on in my head. I think [being on the outside] also makes you think about or question that weirdness of power that can happen between the choreographer and dancers. It can so easily be manipulative. Even to have the power to say: Okay, can you do this? And then, the dancers just do it. I found it a bit weird. I was like: Oh my God, why would they do it? Why would they want to do that? But also, I’m really amazed and grateful for them.

SR: It must be quite warming to see people wanting to do something that you’ve created. But then there’s, as you said, all these power dynamics and questions around ownership.

JC: I don’t ever want to take that for granted. Because I think, some of my experiences as a dancer, really just felt like I was a body. Somebody just wants my body to do things. There’s no care at all for the person who’s doing the thing. It feels really important to keep acknowledging that this is a person having an experience. To acknowledge the whole self of the person. Never take for granted what that person is giving.

SR: Would you be able to explain some of the costumes and the ideas behind the scenic aspects of the piece.

JC: In fire bird, most of the set is this a thread that connects across the stage and creates a sort of web structure. I worked with Tim Spooner, an artist and designer, who came and helped me make the thread a bit stronger and more visible. I think the web was about creating a home. Maybe a place of safety. But also entanglement, feeling trapped in what might feel like home. The different sections of the web also take the idea of different rooms or different parts of the self. In yourself, there are some parts or rooms that you don’t really want to go into.

There’s also a video projection onto the back wall. This came from an artist that I collaborated with called JD Samson for Art Night. I guess [the projection] was about bringing her into the piece and how she expresses her gender identity; it felt important that she was in it somehow.

For m/y-kovsky, there’s not really a set. Originally, we did it in quite a big hall in Walthamstow. That was quite a different space from a theatre space, as people were watching it on all sides, rather than just the front. In that way, the piece is not a spectacle. It’s more like us at work, doing this thing.

SR: Have you had experience collaborating with artists and designers before? Or was this something new for you?

JC: I have worked with both costume and set designers before. Collaborating is hard. I think because I do a lot of stuff in my head, I don’t always have words for it. When things make sense to you, you don’t have to articulate them to someone else. The process of collaborating, and trying to be a better collaborator, has been about trying to communicate better. It can be hard sometimes to say what you think, what you want or don’t want. It’s a very particular kind of relationship. I’m still trying to understand and trying to be better at it.

SR: It’s really interesting thinking of collaboration as a relationship that you’re always working out and negotiating. It’s important to communicate what you want or don’t want, but then sometimes realising you might not even know what you want. And that’s quite an interesting thing that can come from collaboration, because it really does throw out all of these questions that you have to confront.

JC: I think it’s scary as well, because I always feel like there’s a certain perception of: Oh, I should have my shit together, I should know what I want all the time. It’s quite vulnerable to say, actually, I don’t know, or to say, I need help. Maybe not for everyone. But I think for people who are not men, it can be hard to say what you need.

****

Don’t miss out on Jules Cunningham & Company’s double-bill performance of m/y-kovsky and fire bird at Sadler’s Wells, from 10th – 11th November 2022. Find more information and ticket booking here.

For the latest updates on Jules Cunningham, their company and work, check out their Instagram.