Words by Rose Biggin. This article is part of our REWRITE series with Chisenhale Dance Space’s Artist Community.

The categories of artist and activist are becoming ever more entwined as the fault lines in our world continue to reveal themselves. Socially, economically, environmentally, all at once.

I’m writing this article as a member of the CDS Artist community, a collective that is seeking to forefront awareness and progressive politics into its actions and ways oforganising, baking these values into whatever work is made there and how everyone is made welcome in the space.

The reflections are about processes with which we make our art; creative tools of protest; politics in art; and partner funders and ethics. They offer approaches to the topic, hoping that we may feel alive to the spaces for activism within our own practice.

Art that is activism

An artist who considers themselves an activist might not make work that’s explicitly ‘about’ an issue or another. (Although this is definitely an important and valid way to approach the two together – given all the narrative, emotional, aesthetic and cathartic power art can offer. Here’s an example of a performance work that presents political art as a provocation in and of itself – “A collection of short political plays in response to warnings that artists shouldn’t be political.”)

But crucially, even if the work doesn’t forefront the activism in its content, it can be in the processes, the conditions in which it is produced, the wrap-around stuff – the way people are treated in the making, backstage, in the PR, in the life and breath of the whole of the work – not only in what’s presented to an audience.

The activism can take place in terms of other choices: not programming a show at certain institutions; speaking out using the platform of an event where you could just not mention certain topics at all – or when management have specifically urged you not to; coming together as members of an industry to condemn censorship and silence. When artists bring people together – gather audiences, curate separate minds into a community of spectators, listeners, readers, participants, fans – we might call attention to things that are important, and announce where we stand, making use of a public context, as an act of activism.

Context defines things

For many months now, on the national Palestine marches I have been part of a drum group that affiliates with different blocs at each protest. Our purpose is to lend support to the chanting and bring energy and noise to the event.

I turn up as a process of activism (and not as art), while the rhythm that we make collectively is similar enough to music that people may listen and dance to for art-adjacent reasons. The music we play has its origins in samba, and there are similar bands all over the country and internationally who play the same tunes. The music has been shaped, influenced by, and owes much to the black liberation movement, and as such is continuing to be presented as activism. (And it’s fun partly because of what it shares with art.)

I don’t have much of a music practice beyond this drum group, although within my arts practices I often work with musicians.

The drumming we do together is in the context of protest, however the actions and processes it asks of me and the group, and of the chanters around, are in effect pretty similar to what will be asked of musicians in a different context – an art context (however sloppy, punk or community-minded this may be).

But in this case, the tools (drums, parts, sections, form, collectives, etc) become art or activism because of their context, and indeed should a drumming group choose to claim this space as an art space, then perhaps could be both at once.

What else do these two contexts share? Activism is partly about developing a collective, in order to push for change. Art needs an audience and usually tries to insight some reaction from it, and much art looks to offer audiences (in performance) a collective response. They both share the desire to shift something within a collective – or even one-person-at-a-time, should the art or activism operate that way.

Our art will be political whether we want it to or not

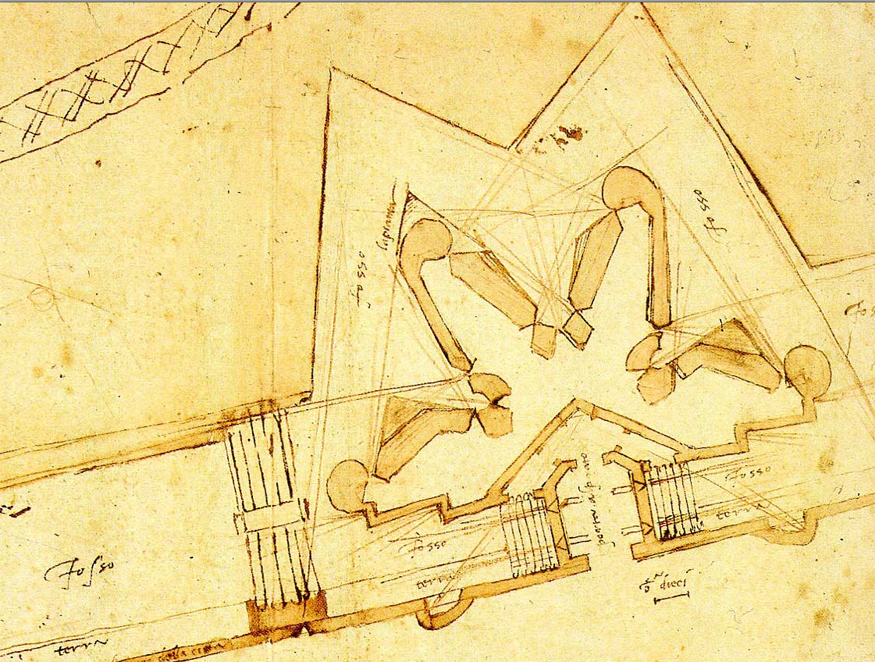

My partner is researching for a new project on the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo, who painted the frescoes on the chapel’s ceiling, spent his artistic career trying to avoid expressing any political allegiances, because Rome and Florence were constantly in turmoil – two competing city-states vying for power. Best to keep your head down and concentrate on the work. He wrote letters throughout his life to all his family urging them not to get embroiled in any politics. But Michelangelo actually had a career that was constantly in service to the propaganda of someone, despite his misgivings on having too much public allegiance in times of radical change. There was a period of his life where he had to defend Florence from the Pope and his armies – at one point designing the Florentine battlements. After Florence fell to Rome, the Pope decided to continue commissioning him, and again in need of a patron Michelanglo accepted.

Even an artist dedicated to not committing to political powers can find themselves forced to make calls. There’s no avoiding it.

Sometimes staying out of things is not much of an option, even if we should tell ourselves it is. And sometimes saying nothing is political.

Corporations and their ethics

Art-making for a public audience usually interfaces with larger infrastructure. Let’s think about Fossil Free Books, a collective of writers and book-workers who believe a fossil fuel free, genocide free book industry is possible. The group was troubled by the fact that the sponsor of several major literary festivals was also profiting from the arms trade. Many authors, from the collective and beyond, announced they would withdraw their labour from these literary events until the sponsor divested from the arms. When given the choice between art or arms, the sponsor dropped all its support of literary festivals in the UK. (Sponsorship won’t love you back). In much mainstream media, blame for this fell upon the activists, those writers who had pointed out the situation and articulated a moral response; the sponsor, keeping their “business investments as usual”, wasn’t seen as the bad-faith actor here.

“In naming a problem, you become the problem,” as Sara Ahmed tells us. And being marked as the problem in the current landscape might feel frightening. It might feel safer to ignore the problem, but of course the next question then is: safer for whom? We don’t make art in a vacuum, and tomorrow’s politics are coming for us.

However, early career artists reading this need not despair.

Artists allied to activist communities can be looked after by their number – for a recent instance, Queers For Palestine organised a grassroots communal boycott of National Student Pride, and artists who lost their fees through withdrawing their labour were remunerated from the collective strike fund. This boycott resulted in the positive and tangible change of NSP returning their investments and committing to greater solidarity.

Taking any size action can feel much more positive than waiting things out. Everyone is learning. Join communities, join up with others and lend amplification to those artists and activists already speaking out.

The interests of the disenfranchised, of the environment, of the many, are not in safe hands within current power structures. One thing seems certain – we increasingly need activism (as well as other tools of community, understanding and change) to ensure we still have a world to make art in.

Biography

Rose Biggin is a writer and theatre artist based in London and a member of Chisenhale Dance Space. Her most recent project is alt. opera Star Quality (Cockpit Theatre 2024) and she is the author of an academic book about immersive theatre (Palgrave), a forthcoming fiction collection (Newcon Press), and two novels.