Words by Sunhi Keller. Performed at Barnard Movement Lab.

Scattered over a marley floor are various frilly dresses, sparkly heels, silver charm necklaces, makeup products, chunky bracelets, and even a baby pink glittery wand. A rolling table sits in the corner of the room, covered in white cloth. As audience members stroll into Barnard Movement Lab after first taking off their shoes, they tiptoe over the array of objects, giggling to their friends when they spot something that reminds them of their own childhoods.

Unfettered: Act I created by Rush Johnston – choreographer, performer, filmmaker, and movement researcher – begins in silence as three projectors shine photos of Johnston from when they were younger onto the white walls behind the stage as an introduction to Johnston’s adolescence. “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” covered by The Mayries fills the speakers as Johnston chassés onto the floor, a smile painted on their face, their eyes filled with possibilities and dreams. They run, skip, and hop over the objects, and bend down to pick up a dress, swinging it over their body. With the joy of a child playing dress up in their mother’s closet, they slip on a pair of high heels, clunk around, and make snow angels in the middle of the stage. Johnston’s work begins in a fantasyland of childhood – girlhood – a place of innocence.

As the music fades out, Johnston props themselves on the table and pulls out a pink journal, flipping through to land on a page. They begin to speak, reciting words and phrases that remind us of girlhood – sleepovers, first crushes, first girl crushes. The passage is evocative as Johnston questions their own self identity within the tropes of girlhood, prompting us to question why gender is placed onto children so early on.

Johnston continues on, dancing to the universally known songs like “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “I Feel Pretty.” They slip on a short, black, feathered dress during “I Feel Pretty,” gaining multiple laughs as they shimmy about in mockery of societal feminine expectations until being interrupted by a recording of Cinderella’s fairy godmother, telling them their beautiful disguise will disappear by a clock’s bell.

As the sound of a clock tower chimes, Johnston gathers the makeup products thrown around the floor and heads offstage. Projected onto the walls are two videos side by side: one is a previously shot video of Johnston reflected in their bathroom mirror, their face covered in white paint, while the other is a live video of them now, sitting in front of the camera as if they can see their reflection. “La donna e mobile” plays and we watch the two videos of Johnston as each one puts on makeup, the images mirroring each other – as one puts on eyeshadow, so does the other – yet the pre-recorded video shows Johnston putting on clown-like makeup, and the live feed is of them applying “regular” makeup. It’s a brilliant allegory for the emotions Johnston feels, not just in the wearing of makeup, but in the societal role it plays in the representation of “woman” and “girl.” In both projections, there is the haunting feeling like Johnston is aware of the illusion of makeup, as if they are aware they are trying to portray someone they are not. Both on-screen versions of Johnston begin applying lipstick, smearing it around, painting over the lines of their lips almost in grotesque fashion. In Unfettered, this is the moment Johnston finally rejects girlhood.

Throughout their vulnerable performance, Johnston shares the importance of shaving their head and their fears of coming out to their family. They pack up the objects littered across the floor into a suitcase then light a candle as a final act of shedding girlhood – a goodbye.

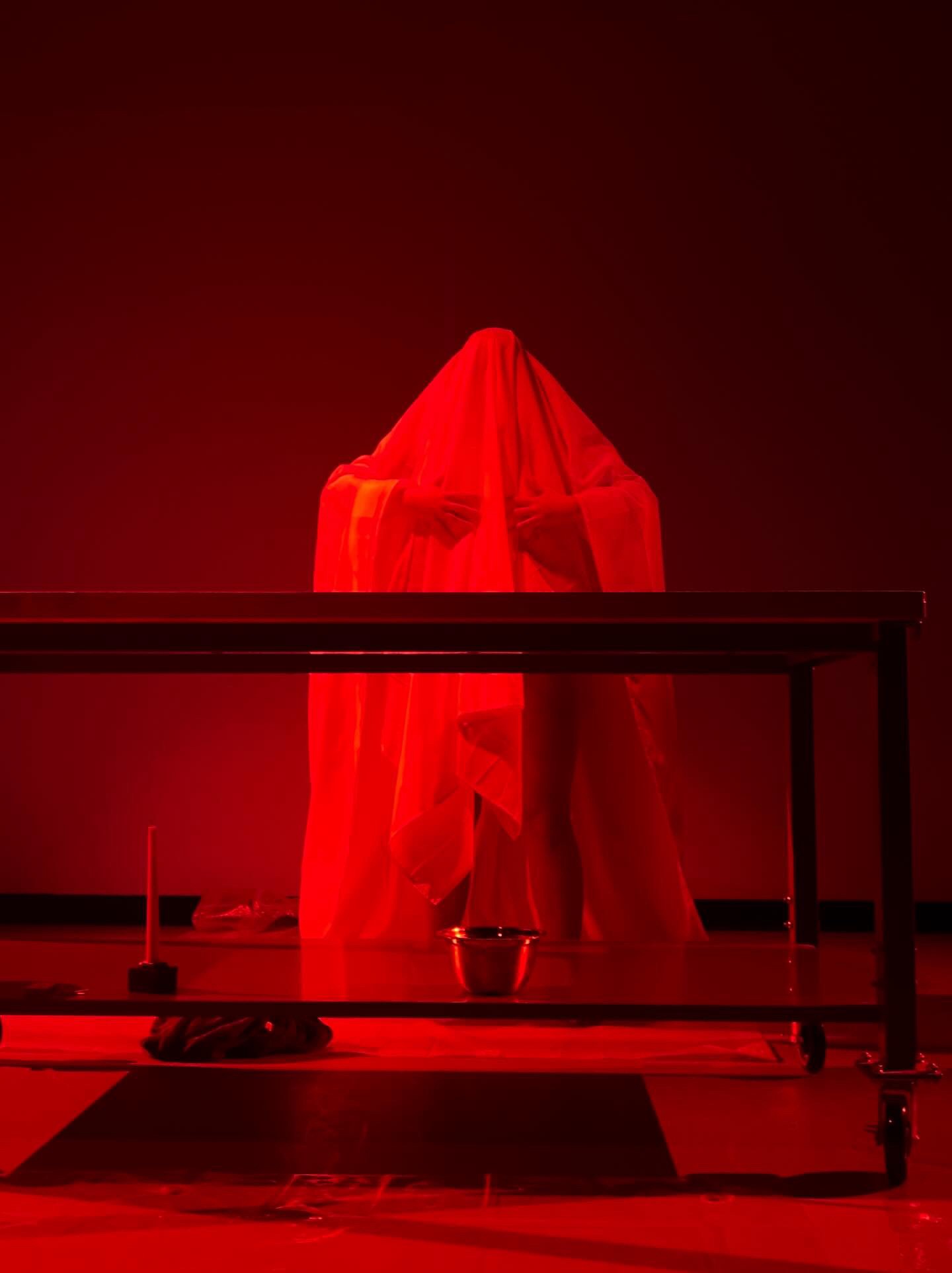

Underneath red lights, Johnston travels to the table, pulls out a bowl, dips their hand in, and paints something on the white cloth using their fingers. Between the lighting and angle, the audience is unable to see what Johnston is doing, and is left in tense anticipation. Once they are finished with the cloth, they lift up their dress, covering their face and revealing their breasts. With their paint-covered hands, they tenderly cradle their breasts, a dedicated farewell before they undergo top surgery. Johnston lifts the sheet, holding it up to show the audience what they have written: “in our image.” They wrap their body in the sheet and crawl onto the table into supine position, laying the painted sheet atop themselves, mimicking a dead body in a morgue. At the last moment they inhale sharply, reaching up towards the sky. They are reborn.