Words by Katie Hagan.

A few months ago we put a call out on our Instagram channel asking our followers to recommend or put us in touch with any Palestinian dance artists and makers. We did it as a way to celebrate and honour Palestinian artists specifically at a time when Palestinian people and voices are oppressed by the Israeli regime and misrepresented by the mainstream media.

We were really grateful to receive quite a few messages and recommendations, including the change-making Alrowwad Cultural and Arts Society, an organisation that works with refugees, mainly women and children, in the Aida camp in Bethlehem.

We were put in touch with Alrowwad’s founder and director Abdelfattah Abusrour (also co-director of Bethlehem Cultural Festival), who we spoke to a few weeks ago over Zoom. Based near the camp, Abdelfattah was very generous with his time and we spoke warmly about Palestine’s cultural and artistic identity, and its misrepresentation. We also spoke honestly and directly about the situation on the ground and the daily reality of living under oppression. There are some difficult moments in this interview so please do take care when reading.

Although there are difficult moments, ultimately my conversation with Abdelfattah was nothing short of impassioned and very powerful. Read on to find out more about the phoenix-like rise of Alrowwad; touring the UK last year and the beauty that comes with resistance.

Q: Why did you start Alrowwad?

A: I was born in Aida refugee camp and was one of the lucky ones to have a scholarship to go and do my studies in France, where I stayed for nine years and returned in 1994. After completing my studies I started working with my biology degree and got a PhD in biological and medical engineering. But my heart was with theatre – it always had been.

I then joined a youth centre where I started training children. But the location of the youth centre was at the entrance of the camp which was in direct confrontation with Israeli occupation. So the idea of creating Alrowwad in 1998 with a group of friends came out of this fear for the lives of children and their exposure to danger. It was started to save and inspire lives, and give possibilities to resist in the most beautiful, creative and peaceful ways.

My purpose was to create a professionally trained children’s theatre group where they tell their stories and histories. And hopefully this would be a way to build peace within themselves or community and maybe change the world.

“We show another image of Palestine that usually the media doesn’t show or ignores”

Q: Why in particular did you focus on the Palestinian youth?

A: I started with children as they were the ones who needed the possibilities; they are most in need and the most targeted. When you have children who even at eight or 10 years old, feel totally helpless, then you have a problem. They believe nobody cares. When the Israeli soldiers come in the night there is no one to protect them. So that is why it was important to give space to children and young adults.

Their parents would say to me: ‘We get used to it’. Do you know how painful it is to hear that people are getting used to occupation, oppression and injustice as it’s part of their normal life? We can’t allow this.

If people are denied even the possibility to express themselves through theatre, dance, art, then things will implode. We want our children to grow up and thrive; be proud of their heritage and achievements; to lead others on a better path.

Q: How does Alrowwad work with the local community?

A: The philosophy of Alrowwad is to work based on the needs of the community, whether that’s through basic things like cooking and managing finances, or through dance and theatre. That is our mission. The idea is to give possibilities and not dictate a code of behaviour. It’s to work with everybody but not under the umbrella of ‘everybody’. For instance, when the Second Intifada started in 2000, we started a supportive education programme for children with trauma and learning difficulties. We started workshops with mothers and families because it was important for them to know how to deal with children under such violence, curfews and incursions and so on.

So many well-meaning humanitarian agencies dehumanise people with their passive forms of charity, instead of helping them keep their humanity and dignity. This was why we wanted to provide possibilities and offer projects on demand. We help all aspects of the community. It ensures we fulfill the need and give them what they want and support them.

“You don’t like a piece of art because it’s American or French, you like it based on how much it touches you”

Q: Do you hope that your activity shows a true representation of Palestine?

A: We show another image of Palestine that the media doesn’t show, or ignores. It was important to present Palestine as it is, which is a land of inclusion and not exclusion. We have the oldest Israelite community in the world. We have different communities living here where the land isn’t the property of any one religion. You come to the old city in Jerusalem and there is an African quarter, a Jewish quarter, an Afghani quarter, Muslim and Christian. We are an inclusive country that welcomes everybody.

Q: Let’s talk about The Camp’s Gate by Alrowwad’s Dabka Dance Group. How did this come about?

A: Palestinian dance is rooted in our ancestral traditions. Our ancestors are mostly peasants working on their lands – you may have heard of the Canaanites. We, Palestinians, are descendants of the Canaanites who started our traditions. Movement is a big part of this tradition, as it is in many indigenous cultures. For Canaanites, the movement might be a rite or a prayer; or hitting the ground with your feet to call for the plants to grow. Little by little the movements evolved and developed, and involved music and song. Dabke was then born.

Certain Dabke movements and steps are specific to certain areas in Palestine and that’s why there are variations between the Syrian, Iraqi, Jordanian and Lebanese versions.

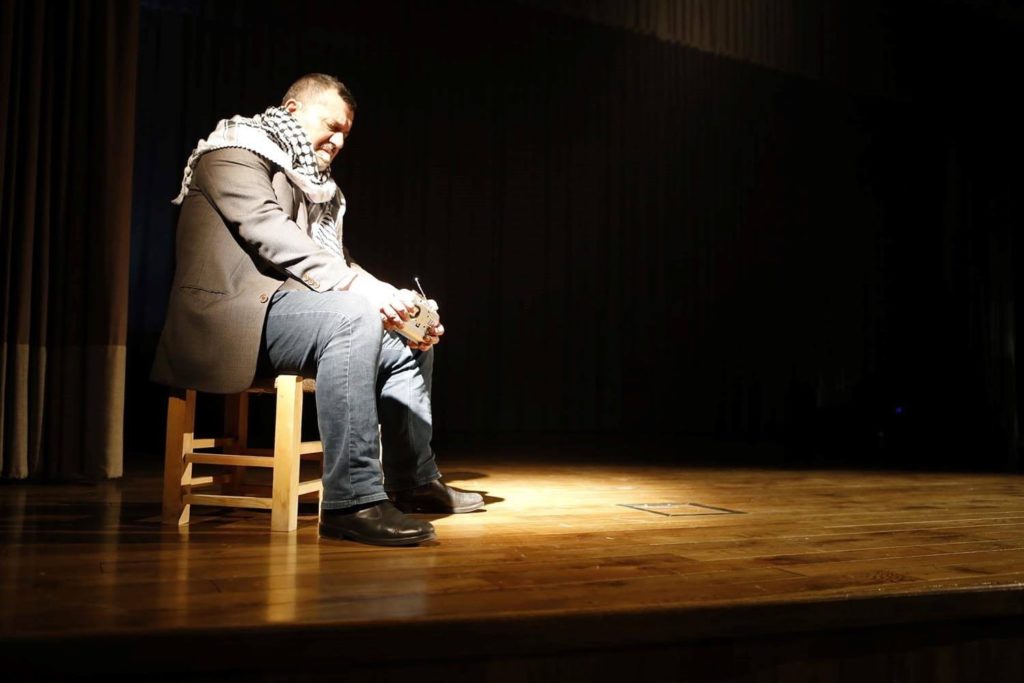

Dabke is one way to communicate the tradition and assert cultural identity during oppression. The Camp’s Gate, which toured the UK in 2022 and was seen at the Bethlehem Cultural Festival, is all about one refugee telling their story, my story, and let’s say my parent’s stories too. The dance reflects on themes such as Nabka, ethnic cleansing, resistance and attachment to land. It also reflects on Alrowwad’s ethos of beautiful resistance, one way or another.

There were around six dancers, three boys and three girls, based within and outside of the Aida camp. I did the dramatic monologues for The Camp’s Gate and the young people were dancing my words and telling my story. It was a composition of different personalities detailing what it means to be a refugee.

Q: What was audience reception?

A: It was very positively received, a lot of standing ovations! Then we had a post-show discussion and there was a lot of admiration for resilience and resistance from young people who express themselves in such beautiful and creative ways and remain truthful to their identity and humanity.

Q: How can art help right now?

A: I believe the power of art at a human level. You don’t like a piece of art because it’s American or French, you like it based on how much it touches you. It puts people on equal grounds and sees one another as equals; not as inferior or superior. And these are the bridges that we can build together.

Art is an important way to prevent people from being brainwashed politically and believing stereotypes. I don’t believe the arts will resolve everything but it plays a role in restoring humanity. It is an important tool to create better understanding and possibilities for the future, especially for young people as changemakers, helping them understand what is just and right. It is also a legitimate way to resist occupation and instill peace.

To find out more about Alrowwad, visit its website: https://www.alrowwad.org/en/