Words by Francesca Matthys.

A gasp of breath and shudders of whispers lure us into the haunted world of It Begins in Darkness by Seke Chimutengwende. We are immediately thrown into panic, loss, uncertainty and fear that sets up the emotional terrain of the work. Hyper awareness of emotions and sensations of the flesh and bones.

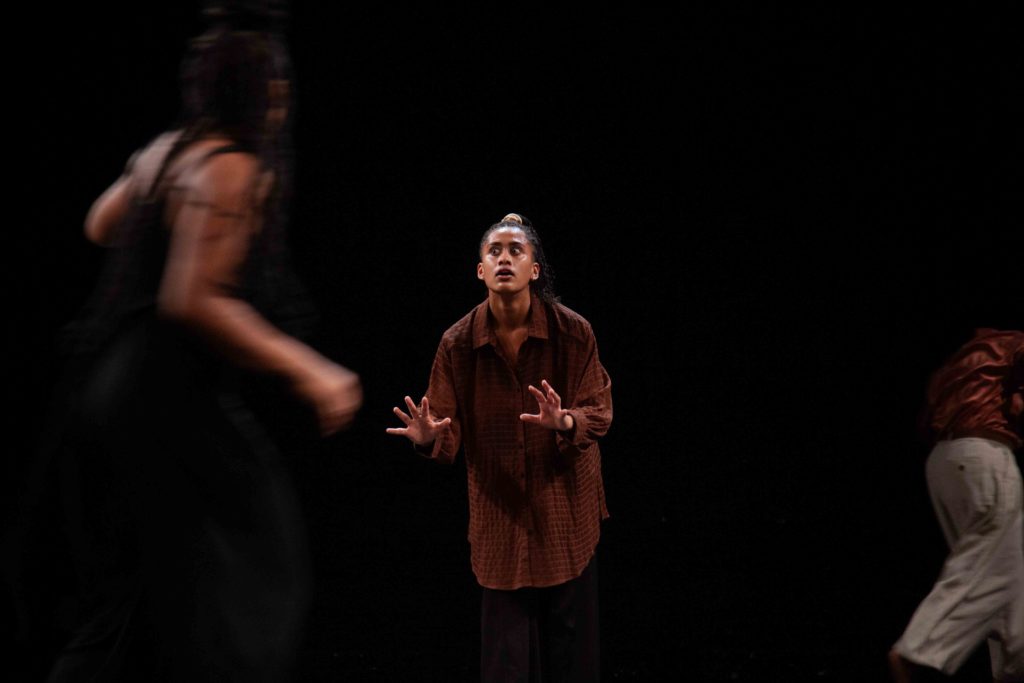

The performers sense the thick air and raise their arms to the heavens as if surrendering to a higher power [to save them] or look down towards their death. An eerie humming begins, like the quiet drum of churchgoers or mournful people at a funeral. Ghosts. The element of sound is thoughtfully integrated in this work as many of the sounds are generated from their performers themselves, microphones on the floor echoing their frantic shuffling.

For a moment I drift out of the mystical world to acknowledge five black bodies on stage, a reassuring reality I don’t see very often in London. This work is in conversation with the ghosts of slavery and colonialism, and seeing black bodies interrogate and fight these demons, through the black lens, is poignant and moving.

The performers wear blouses, suit pieces and silk shirts. It’s dressy attire and bare feet as if they have been unexpectedly taken from a party, work or their daily lives against their will. Have they been here much longer than we think?

Choreographer Seke Chimutengwende is inspired by film directors such as Jordan Peele and as the performers begin to embody and describe a home. I think of plantation farm houses, with their ticking wooden clocks and high ceilings, that hold the terrors of time. It is as if the performers are spirits trapped in this house, indefinitely tracing through their yesterdays. These tracing movements such as hunched backs resemble our ancestral foremothers carrying babies or sweeping floors, illustrating that above all, the body remembers and certainly holds many experiences, especially trauma.

The ensemble moves through many repetitive, compulsive movements that signify their past selves and people. Through this I reflect on the potential impact that embodying these stories may have on the performers as possible as descendants of these experiences. It is a weighted affair.

As the performers repeat their individual compulsions on loop, walk past each other in a routine manner, to the sounds of hollow knocking from above, I wonder if we are in purgatory where they must try to change the configuration of their current circumstances. The moments of silence and pause allude to the process of ancestral grieving and how sometimes all we can do is do nothing until the dull pain passes. If this really is purgatory, the ghosts of this place continue to wait and indulge in arbitrary play to pass the time, a pleasant shift of energy after the dense nature of the emotion. Within this lifted energy, the performers engage in what resembles social dances, recognisable from various African cultures and done at celebrations such as weddings, in an attempt to connect, to foster community, conjure up their ancestors or just indulge in a fleeting moment of pleasure. These ghosts become angry as this dance now becomes grotesque. There is a flurry of emotions within this trajectory that Chimutengwende and the ensemble balance well in a way that is unexpected and intentional.

The work offers a unique movement vocabulary in its arch of intense emotions such as a ‘shaking’ solo by Mayowa Ogunnaike that is nuanced and intricate. The ensemble all stood together in a clump organically transitioning from crying to wailing to laughing to shouting in sheer hysteria or agony. It is an evocative and startling moment. The throat chakra in Yogic philosophy is connected to our ability to speak our truth or own our unique voice in the world and as the performers root themselves firmly, it is as if they purge or release an afterbirth of trauma that has brewed silence within their lineage. It is powerful to see this done collectively, reminding us that only as a collective may we truly heal.

This concludes with a solo by performer Kassichana Okene-Jameson lying down on the floor, motionless, an image reminiscent of black bodies that have endured violence.

The text included in the work namely statements such as ‘…bodies as private property’ is a direct ode to how slavery dehumanised black bodies. To hear this as the performers completely embody these emotional terrors is powerful.

The closing image of the work leaves us to process what we have experienced as the light cinematically compresses on stage. In this final image the performers are no longer on stage. Perhaps they have healed, perhaps they have gone on to find elsewhere to mourn. Either way, the experiences of the past may always haunt us.

Credits:

Conceived and directed by: Seke Chimutengwende

Choreography and text: Seke Chimutengwende with the dancers

Dancers: Isaac Ouro-Gnao, Adrienne Ming, Mayowa Ogunnaike, Kassichana Okene-Jameson and Natifah White

Created with input from Alethia Antonia

Original cast: Rhys Dennis and Rose Sall Sao

Dramaturgy: Charlie Ashwell

Lighting design: Marty Langthorne

Costume design: Annie Pender

Composer: Aisha Orazbayeva

Double-bass on soundscore: Hugo Abraham

Sound technician: Michael Picknett

Vocal coaching: Randolph Matthews

Research consultant for the R&D phase: Sita Balani

Production: Lucia Fortune-Ely, Metal and Water

Producer 2022 and 2023 Tour Planning: Eve Veglio-Hüner

Company teachers: Seke Chimutengwende, Shannelle Fergus