Written as a provocation piece for the Clore Leadership Fellowship, this paper a call to action for increased levels of care, respect and safety for artists in the UK dance sector, representing Richard Chappell’s views only.

“Not an ounce excessive, not an inch too little,

Our easy reciprocations. You let me know

The way a boat would feel, if it could feel,

The intimate support of water.”

-True ways of knowing, Norman McCaig

I make dance. I am the sum total of my lived experiences and the way I choreograph helps me to make sense of the world around me. My experiences, both wonderful and devastating, have shaped my beliefs and values, fuelling my artistic processes. Each creation I make is something I have to get out of my system and the vulnerability and empowerment I have found through collaborative relationships with artists has shaped the person I am today.

The more I connect with people, the more I see the hardship dancers and dance makers hold in their bodies. We facilitate nuanced and rich forms of expression and finding the strength for this can manifest absorbed trauma in unhealthy and, in extreme cases, abusive ways. Dancers are primed with energy, working to endurance limits and travelling to where the, often low paid, work is. It requires great personal strength, and emotional pain or injury can be held in the body long after physical healing. This pain can manifest in destructive ways for dancers, whether they be early career artists or our most senior leaders. Often people project their pain onto others, or maintain an elitist and inaccessible system because their values have been shaped by their past. Most of our current systems for training and employment perpetuate and amplify hardship, building up raw emotional energy over time, creating access barriers and perpetuating trauma. We need broad strategic reform and generous spiritual change. We all, me included, need some good healing.

Taking inspiration from dramaturg Peggy Olislaegers, I am a Dance Activist: someone who believes in the transformational power of dance to heal people, like it has healed me and so many around me. I believe our dance landscape can become safer and more accessible, celebrating emotional intelligence instead of resilience. Our brilliant workforce is the answer and the care we give inwardly will radiate outwards to our communities and audiences. Tension in the body is often associated with strength but the strength we need will come from letting go and treating others differently to how we were treated.

I am expressing my personal desires and dreams. Other brilliant artists think and act differently. Compassionate dialogue around our differences is what will help the sector grow. Personal circumstance and privilege plays a huge part in what people can dream and give. People who disagree with elements of my writing will be just as much part of the cultural change as I am. If you think this paper’s call to action is naive, I want to listen, learn and talk.

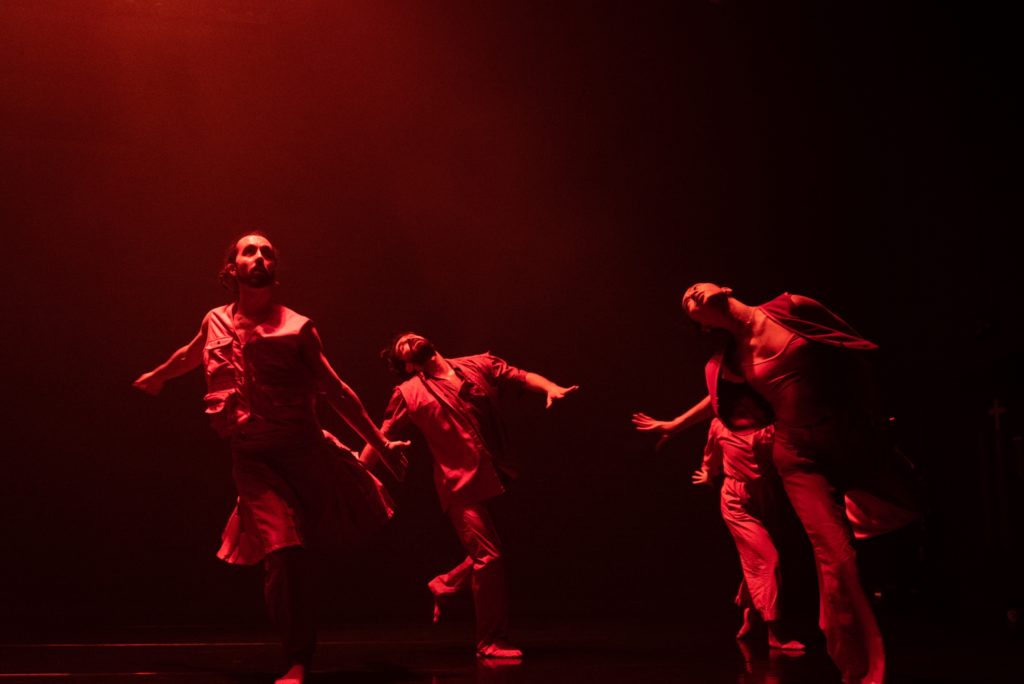

As a choreographer, I counteract the embedded trauma dancers have by actively building them up, instead of breaking them down. I collaborate with freelancers who have fine-tuned their generosity and who glow with peripheral care for each other. Assimilating into new spaces constantly can be disorientating, resulting in a loss of belonging. Jonathan Burrows in A Choreographer’s Handbook says brilliantly there are no mistakes when starting a process. My addition would be, ‘as long as everyone belongs’. When everyone belongs, dance cultivates strength, rapport, care and trust. These feelings progressively soar, like heart-thumping electronic music. My recent training in Neuro Linguistics Programming has shifted the way I listen and offer critical feedback. Listening and questioning is how I make my dances. Exercises like Positive State Anchoring nurture safe environments, and validate emotions and voices. They are generators of strength and empathy.

“Dancers pushing through pain is indoctrinated in the sentiment of our art form.”

It’s not all rose-tinted glasses and rainbows. The work is exceptionally vigorous; it is physically and emotionally exhausting, requiring regular dialogue to ensure safety. The dancers we work with are breathtakingly strong people, and boldly expand past their perceived limits. Our responsibility extends to empowering them so they know they are more than their job and practice. Performing as one of five dancers in a one hour piece is wild and relentless, requiring each dancer to carry others when strong and accept being carried when exhausted. Their values and tactility are tested at minute 40. Sharing sweat is a good way to form bonds. Our ensemble values are spoken: care, empathy, challenge, vulnerability and togetherness. I exude faith in each dancer’s ability, falling for their dancing so they fall for the work. A way to get dancers to fall for the work without force is to include them. The way mid to large scale dance is produced usually means dancers are the last artists entering a process. They are also regularly the least paid. Dancers feel work uniquely and their expertise from the beginning makes the spectacles of light, sound and movement that I buoyantly create possible. They are co-choreographers, so their beliefs are integral as creators.

Although I am focusing in this writing on care for dancers, change can only be instigated if it extends to all cultural workers. Producing, marketing and production teams are equally squeezed and strained. When restorative values shape roles, better overall collaboration will be fostered and invisible departmental walls removed, grounding whole teams.

From rapidly decreasing funding for companies in the cost of living crisis to compressed remount expectations, there are many obstacles to making work safely. Despite sometimes the best intentions, solutions rarely land perfectly and, regretfully, compromise is sometimes essential. As I work in regions with exceptionally low dance provisions, I live and breathe these challenges and do not get everything right (no one can). I believe passionately that if we address our values with an intention of healing, community-led innovation will present solutions with minimal compromise. The challenges dance leaders face take a toll. Our art form has become tunnel-visioned and survivalist. Instead of speeding down a dark tunnel, we need to run in open fields. Our values are intrinsically linked to how we see the world and are the first thing that needs addressing.

Safety is essential for career sustainability. It creates the armour, strength and integrity that’s needed for when challenges inevitably occur. During the Clore Fellowship, our cohort verbalised and wrote working agreements, acting as a touch stone for our conduct, promoting radical honesty. In our new company creation Hot House, we outlined our own agreements, giving new dancers a voice to express their safety needs. These covered consent, expression, boundaries and injury prevention. It ensured that our communication skills evolved alongside the production and allowed us to confront challenges with context and emotional intelligence. This enhanced productivity and formed bonds of belonging, which became the message of the show.

Helmed by Artistic Director Martin Forsberg and co-authored and signed by everyone within the organisation, Norrdans (Sweden) has an articulate and ethical Code of Conduct. During my study visit, I saw a safe environment that allowed their ensemble to artistically flourish, exuding bold ensemble strength and individual integrity. Our newly created Code of Conduct varies subtly from Norrdans’. Every organisation’s values, objectives and operations differ, requiring different policy content. Our policy gives our dancers a mutual understanding of safeguarding and our working methods at the point of contract. Safeguarding overviews should be universal to ensure sector consistency. To ensure companies adhere to these policies, I believe boards should undertake annual company culture audits, minimising the risk of superficial change. It is a misconception that conduct policies restrict creativity, spontaneity and risk taking. My processes are chaotic at best and our safeguarding builds the agency needed for all that messy chaos to flourish.

Ethical governance and policies make sanctuaries for artists. Dancers are regularly asked to draw from their past experiences, emotions and stories. Dancing can cathartically release these experiences from the body, or embrace them. This comes with emotional risk because not everyone wants or needs the same catharsis and catharsis can sometimes brutally unearth past trauma. Boundaries, from auditions to performance, are often not given to dancers, as well as access to professional support. As we demand more from people’s dancing, we should demand more from our care-giving.

To create a safer industry, many different facets of the sector need to work in dialogue to support the education of dance leaders to be ethical and responsible employers. Whether their origins were as dancers in repertory companies or as independents, many artists are thrust into leadership with little opportunity for learning. I believe we should embed training into our development offerings through investment from arts councils, companies, unions, higher education and dance agencies. Only together can we find the solutions needed for our existing and future leaders. Last year I led sessions in conflict resolution, pay negotiation and HR procedures at Rambert School and the students’ understanding of self worth was inspirational. Our future is bright.

“Many organisations look for concise definitions of an artist’s brand: dance ‘and’ technology, dance ‘and’ music.”

Our brilliant dance agencies in England do not always analyse guest company conduct to their dancers to the same level of detail as they do with their own employees safeguarding. This facilitates companies working with freelancers in ways which contradict the values of the organisations commissioning them, and has included: transphobia and other forms of hate, workplace intimidation and bullying and the financial exploitation of dancers through development and recruitment programmes. More universalised Codes of Conduct would ensure artists have to work safely with freelancers should they choose to accept support from a venue, and could present whistleblowing routes for workers. CEO Alistair Spalding explained in conversation how the HR policies of Sadler’s Wells extended to performers for their produced productions. Although there are complexities for how to protect dancers who are not directly employed by venues, learning from Norrdans would be positive next steps in safeguarding.

Safety should factor into shaping how, and what, work is commissioned. Artists relying on multiple open calls a year for career momentum undertake time-consuming processes voluntarily, which minimise income and creates barriers for economically disadvantaged people. If open calls are deemed the most accessible route, I believe articulating safety standards should be a key expectation. As a sector we are rightly and urgently calling for more diversity and representation in our ecologies, covering race, neurodiversity, disability, gender, age, genre and economic background. I believe a lapse in safety standards has occurred through commissioning trends for artists to create work centred explicitly on identity. Should artists choose to make this work themselves, then they should be championed. However, true equity will only be achieved when artists can make work about anything, as their diversity is a part of them and is present in all their creative outputs. A sector where diverse artists need to make personally autobiographic work to get support places long-term weight on their mental health. Placing the artist first supports long term momentum, encourages creative freedom and builds a body of work.

As an artist who has recently experienced upscaling, I have observed the clarity necessary in branding, in order to build relationships and celebrating connectivity is rarely viewed as viable. Many organisations look for concise definitions of an artist’s brand: dance ‘and’ technology, dance ‘and’ music. For many, dance ‘and’ connectivity is too abstract, which could be why our sector can be so apathetic. If this culture changes, I believe pockets of best practice would catalyse spiritual healing. Dance and togetherness resonates with audiences who yearn for connection through kinaesthetic empathy and immersion. People need connection and, I challenge anyone that states that togetherness as a key selling point is inaccessible.

Dancers often face the same economic disadvantage as the audiences we want to reach. We need to create accessible routes into the sector for working class people by ensuring freelancers earn considerably more money. Being a freelance dance artist is like getting slapped in the face once a week or month when it’s good and every other day, or every day, when it’s bad. Changing how artists are engaged within organisations will support them to navigate their complex working timelines to earn more. During a study visit to Scottish Dance Theatre I reflected on this with Artistic Director Joan Clevillé, whose company is composed of both full time dancers and freelance artists employed for individual productions. This works well alongside the activity of ensembles like mine who can currently only offer shorter contracts, as artists can engage with both companies in a year. Joan’s understanding that artists who leave bring new flavours and further diversify SDT when they return was enlightening. When matched with their policies around class flexibility and working day structures, it’s clear how the company champions and prioritises mutual respect. Freelancer sustainability benefits everyone.

Procedural safety policies matched with values of care enrich communities. Togetherness breaks the barrier between performance, and participation and cementing ethical values internally can bleed authentically into memorable place making. Our work is strongly influenced by the stories and choreographies of local people. I welcome them into our spaces with the same spirit as I do professionals. Stemming from my experiences as a Support Worker, my practice has nuanced similarities with all the different and diverse people I work with because of my values.

Companies regularly employ exceptionally talented dance artists to engagement departments, whose understanding of accessibility is essential for our sector. However, their inclusivity is not always reflected in how senior leaderships interact with company dancers. As companies expand, growth often obscures value structures and departments become isolated. Company dancers are often the faces of organisations and can create remarkably enduring memories for local people when they meet them both on stage or in community spaces. Professional dancers regularly associate bravery with achieving physical acts of risk and experiencing the every day courage of communities trains empathy and perspective.

I pour a lot of myself into my work and regularly feel empty. I am immensely passionate about making and activism and I often struggle to visualise existence without my practice. This has led to a damaging pattern where I prioritised treating others better than I treat myself. The effort I am now placing on self care is something I want to encourage in others. Dance leadership is lonely, all-consuming and emotionally battering. Family can be neglected. Health is compromised. If we cannot learn to take care of ourselves, how can we take care of others? When I have delegated and prioritised self care, my colleagues have taken the reins and allowed me to float. This comes with an inevitable acceptance that not everything will always go to plan, but it didn’t when I held everything anyway. Sustainable working processes take time to grow. We need to find economically viable ways for our workforce to decelerate and rest.

Dancers pushing through pain is indoctrinated in the sentiment of our art form and the systems for dancers to get work reflects this subjugation. Five day unpaid auditions and insufficient funds assigned to dancers’ pay create barriers to access and diversity by some of the most well-funded UK companies. Insufficient rehabilitation support and contract cancellation upon injury minimise job security and physical safety and, when combined with frequent workplace bullying, paints a stark image of the dangers of working as a dancer in the UK’s most competitive spaces. The culture of dancers being forced to push themselves to limits, when said push is not a reciprocal relationship of safe learning, devalues dancer’s voices and enables abuse. It’s not enough to order dancers to push themselves. Instead, we should be interrogating how the provision of adequate care can create the circumstances needed for us all to boldly stretch the art form forwards.

I will always fight for change with defiant insistence of better and more ethical practice. Many people will say my introspection on values and ethics is rooted in something utopian which cannot coexist with the current landscape, or will compromise the quality of work. To them, I say, why? The solutions to the sector’s challenges won’t be solved by people whose power rests in the status quo. It may not be solved by the people that will replace them. Instead, I have faith that care will be grown and dispersed by artists from the ground up in our communities, studios and stages. If we pour energy into healing the workplace we love so dearly, then we can carry each other and our art form. This groundswell of change-making energy is a bus many brilliant people choose to ride every day. It stops regularly for people to get on board.