By Giordana Patumi.

On Wednesday January 29th the Batsheva Dance Company, one of the most famous and acclaimed dance companies in the world, took the to stage of Teatro Valli in Reggio Emilia. It presented its Italian premiere of Venezuela, choreographed by its former director and now resident choreographer, Ohad Naharin.

In Venezuela, there are two sides to every move. The choreography is performed for 40 minutes and then repeated with different lighting (by Avi Yona Bueno) and music (designed and edited by Maxim Waratt, Mr. Naharin’s pseudonym). As Naharin puts it, a “scope of sensations” comes over the audience as the curtain rises on a pool of dancers slowly drifting upstage. A collective presence has the audience zeroed-in on this “What will they do next?” performance. The piece brings to the fore conflicts between dialogue, bodies and cultures, and through its soundtrack, refers to a specific socio-cultural and political context not necessarily linked to the South American country, as we should expect from its name.

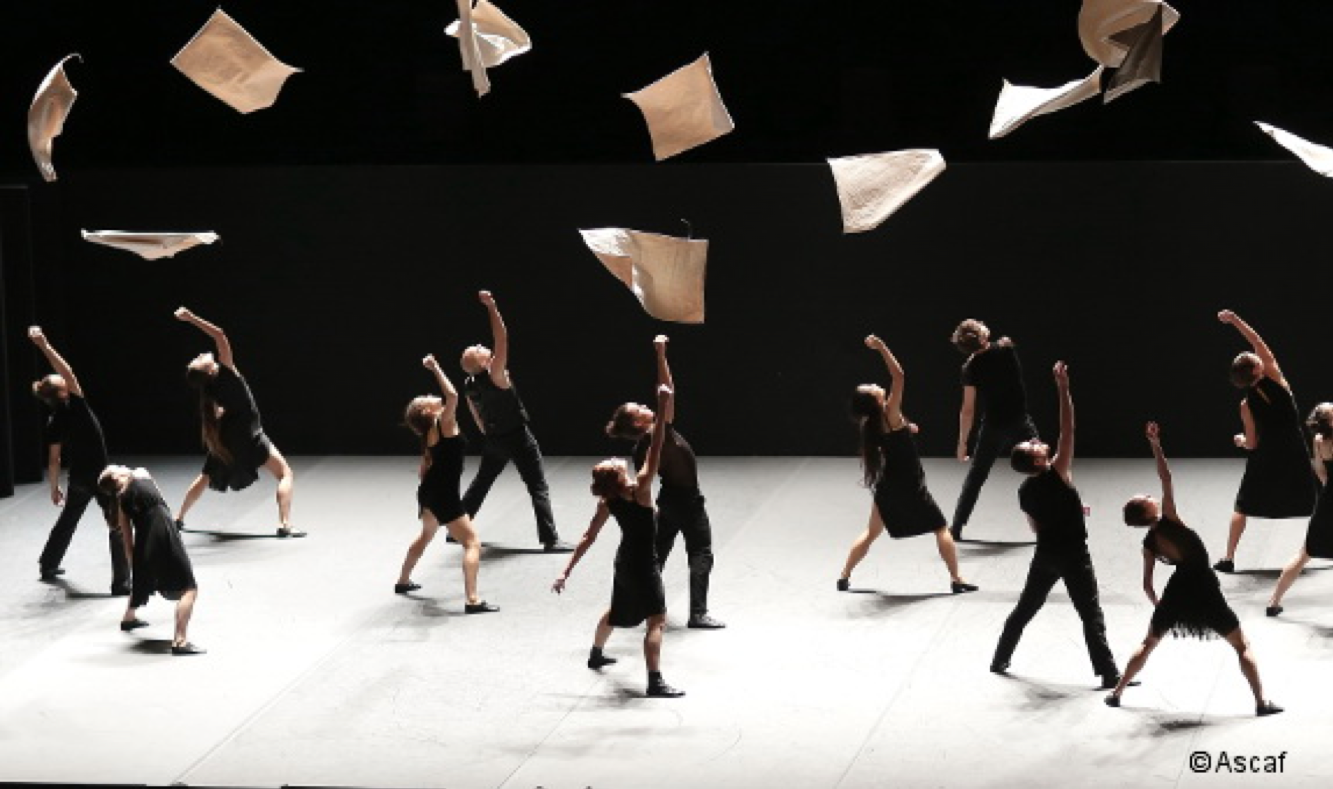

While the Gregorian chant: Alma Redemptoris Mater starts, the dancers with their backs to the audience inch ahead in tiny steps as their bodies lean quietly from side to side. As this mini-procession begins, one of the dancers, Maayan Sheinfeld, strikes a Latin ballroom pose as the group continues to move upstage. Five female dancers walk downstage as five male dancers crawl behind, as if they were becoming strange creatures. The first part of the piece ends with an explosion of solos, where the strength of each individual’s movers, influenced by the Gaga language, finds its highest point. The flexion in the spinal articulation flows like a wave, and the reverberation of the physical bodies reaches high. Naharin is not just a choreographer, he has crafted one of the strongest dance ensembles on the planet, where the dancers understand movement at a cellular level.

Quite suddenly, it’s lights up and we’re back to the beginning. The Wait by Olafur Arnalds starts to play, but the same choreography as Venezuela’s beginning reappears. It’s the same two Latin ballroom poses that broke out of the previous ensemble. So what exactly has changed?

Nothing and everything, as Naharin proves in this excellent and stringent piece. Showing the same dance back to back with different elements is not groundbreaking, but it is powerful in Venezuela. This stark, nuanced work is both of its own world and a reflection of the greater one. But in the second half, which feels like the darker, late-night version, the recording is played over the loudspeakers. The dancers rap here too more loudly, and again join in at the same time to deliver a rebellious message: “The weak or the strong, who got it goin’ on; You’re dead wrong”. The section of five women riding on the backs of five men suddenly transforms, cushioned by the music, Ae Ajnabi by Mahalakshmi & Udit Narayan. The women become queens riding their elephants on an Indian runway. Hot, heavy and even sexual, the subtle shifts in uplighting, music, dancers, and adds colour to the props.

But even with the differences between the two halves, the emotional atmosphere is never totally clear-cut.

All of Naharin’s dances depict bodies in time and space; they about released possibilities for form and framing choreographic conditions. Venezuela is not a randomly chosen title, and it is not ‘about’ the historical, socio-economic, political or current conditions of the nation. In our interview, Naharin said:

“Let’s say that somebody doesn’t even know that there is a country named Venezuela, and the two of you are two extremes. You both watch the show. Ideally you should have an experience that does not connect to the point of reference or the lack of knowledge of what the name is. You agree? Ideally. So, if you don’t know or you haven’t seen Venezuela, Venezuela is made out of two parts where the second part repeats the first part, almost the same choreography but with different elements of music and props. One of the main reasons that I’m researching this experience for the audience is about that troublesome ‘point of reference’. When you see the first part, you hear Gregorian music and you can feel the religious connotations, you see ballroom dancing. When you see the white flags, you think about surrendering or whatever. You see elements that can give you points of reference like ballet steps; you see a lot of things that can give you points of reference and they affect your experience.“

“In the second part I believe most of what you imagine is informed by the first. You see the second part and the point of reference that you have, in this moment, is the first part. I’m manipulating your reference point in order to create a fresh, new experience. We shouldn’t let it influence us too much. And this is part of the overall idea which I based Venezuela on.”

“Now I’ve said this, you may ask why I called it Venezuela? Actually, I have two stories. I’ll tell you the first one. When I wanted to give the work a name, I took a globe and I rolled it, closed my eyes and put my finger down. And when I opened my eyes, it was Venezuela. That’s a good story. But that’s not the reason: I made it up!”

“I made up this story because it’s the easiest way for me to let go of the responsibility of explaining something that doesn’t really need an explanation. We shouldn’t take names too seriously just like we shouldn’t take symbols too seriously. If I look at Facebook there must be half a million Venezuelas; not only the country, I’m sure there are girls named Venezuela, restaurants named Venezuela, in Bangladesh maybe. Venezuela is a used name already. But the real reason I used Venezuela, first of all, I really like the word. I find that word sounds beautiful phonetically. I feel there is something very feminine about it. I like that it’s made out of Ve-ne-zu-e-la, so many syllables. I like it for that.”

“In Hebrew, we have what we call ‘Vav hachibur’ which means Ve. If I say, ‘me and you’ I would say ‘ani Ve-ata’. The Ve- is the first vowel of Venezuela so I called it ‘Nezuela Venezuela’ for a while. Nezuela Venezuela, like a couple. But then I realized that it doesn’t work anywhere else, just with people who speak Hebrew. So I cut the beginning and I was just left with Venezuela.”

“I’m aware of the suffering of innocent people, but I don’t feel there should be a problem because I don’t disrespect it, I don’t judge it, I don’t criticize it… It is Venezuela.”

Images: Ascaf.