The inaugural London International Screen Dance Festival debuts this week, 19th-20th September, at the prestigious Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music & Dance. Curated by independent choreographer, Charles Linehan, the festival will feature 24 films from five continents, all presenting the experimental union of moving image, the screen, movement and choreography.

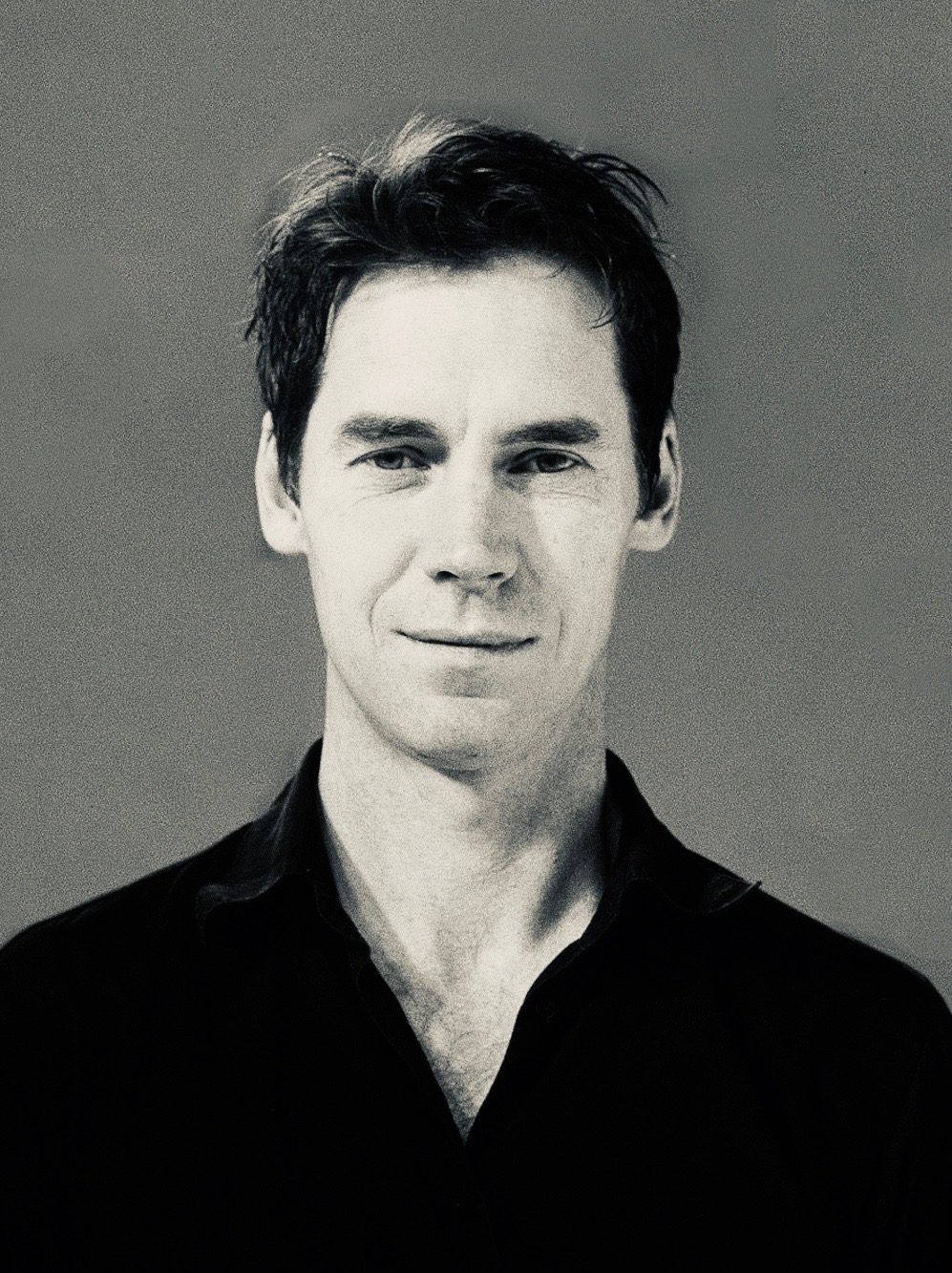

Before the festival opens on Thursday, Charles sits with the dance art journal to discuss why he decided to curate the event, the performances we will see and why dance translates so well onto the screen.

Q: Could you tell me about the London International Screen Dance Festival?

A: The London International Screen Dance Festival is a two day event dedicated to films about movement and dance. I have curated the festival with panel members Stephanie Schober (dance artist and Trinity Laban teacher), Zoi Dimitriou (dance artist and Research Active Lecturer in Dance at Trinity Laban) and Ian Peppiatt (Trinity Laban’s Audio Visual Advisor).

In this inaugural festival we’ll be showing 24 films from five continents including five world premieres from the UK, USA, France, and Australia.

Q: How has your career led you to take on the role as the festival’s curator?

A: Having had my own film shown at international festivals, I have become familiar with the mechanics of how filmmakers apply, what the process is, how the films are disseminated and what the festivals say about themselves. I have just returned from POOL: INTERNATIONALES TanzFilmFestival in Berlin where my own dance film The Shadow Drone Project received an award.

I thought it would be great to find a way to discover originality by inviting people to submit films from around the world. Trinity Laban, with all its fantastic facilities and infrastructure, was an ideal place to present such an event.

Q: What types of performances will we see?

A: A huge range — from scenes performed in a Cuban cinema to the Spurn lighthouse near Hull, from the Paris Metro to the Arizona desert. The films include a diverse range of performers. The festival also acts as a level playing field where quality is prioritised regardless of profile or status. For example, a student film is being presented in the same space as a film by an experienced artist.

On Friday 20th September at 18:00, before the screenings, I’ll be having an informal conversation with the French filmmaker Fu Le, whose film MASS is a 10 minute single take, which will screen on 19th September. To date, this film has been selected in 55 festivals in 29 countries. Entry to this conversation session is free for festival ticket holders.

Q: Why does dance work on screen? When doesn’t it work on screen?

A: Dance film-making in the 1980s and 1990s (with a few exceptions including David Hinton, Rosemary Butcher) had been, to a great degree, controlled by production companies with access to resources and funding.

But with more recent developments in digital technology reducing the cost and accessibility of kit and editing software, films can be made by anyone with a mind to. It’s the democratisation of film making and only good can come of it.

Generally, choreographers have a natural understanding of what they want to do, how it happens, the dynamic of it, the editing of it and how it is seen. All these things translate very easily to film. Perhaps some choreographers just need technical support to express their ideas and intentions on film. In contrast to this, a film director might lack the intimacy and understanding of the dance artform which can give his/her films a feeling of misalignment.

What’s also interesting in this situation is the hierarchical dynamic, one in which the (often male) film director has had a dominant role. This has to do with traditional roles and more than likely, access to funds. Fortunately, this negative culture has been largely disinherited and this is evidenced in the films in the festival.

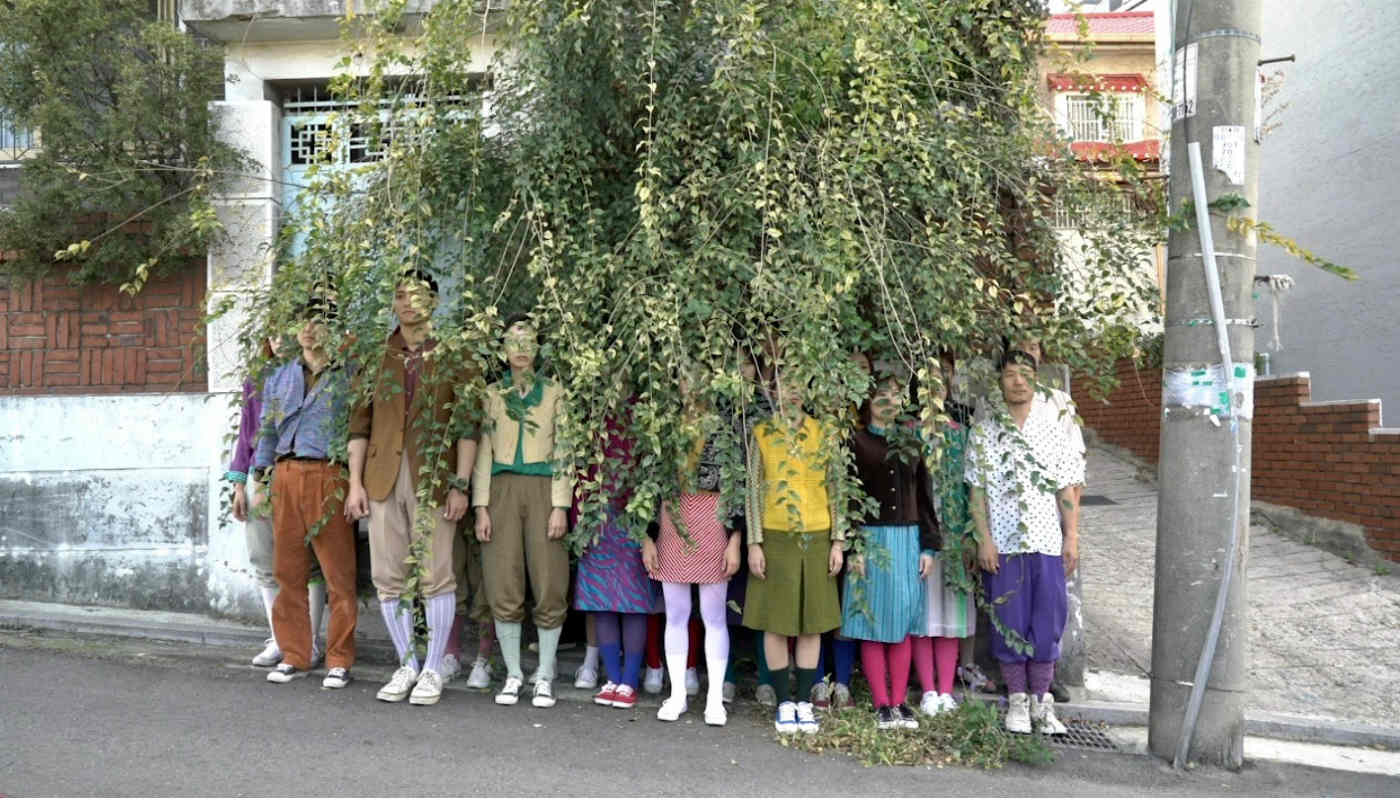

For dance films to work on screen, the level of choreographic work needs to be exceptional, as does the filming and the original idea. It all needs to be integrated. The people who do this best are most often the choreographers themselves. Joowon Song’s film A Town with a Blue Hill (programmed in the 2019 festival) is an example of this; a poetic portrayal of a historical neighbourhood sentenced to death in the name of urban redevelopment in South Korea.

I also have to mention some incredible films from the 70s by amazing New York choreographers (for example, Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen and Meredith Monk’s Quarry). Hopefully we will be able find a way of showing these films in 2021.

On another note there is nothing like live performance, and posthumous film versions of dance projects should not be used as an excuse to cut fees or curtail contracts for dancers just because it’s cheaper to press the play button.

Q: Choreographically, what is next for you?

A: There will be a Charles Linehan Company premiere in London next year – a double bill comprising a quartet and a male duet for Robert Clark and Samuel Kennedy. It is integrated with the film and it initially got me into all of this.

London International Screen Dance Festival will be presented at the Laban Theatre. For more information and to buy tickets, head to Laban’s website.