Taking place on 13th September, Concrete Rain Festival presented a smorgasbord of dance created by East Asian choreographers and dancers.

A celebration of the quiet force and eternal beauty of East Asian dance, Concrete Rain Festival (produced by Slash Arts and Neverland Space Theatre) presented eight works exploring topics including the underworld, brutalism, authenticity and censorship.

Our writers had the pleasure of attending the festival and share their reflections below:

Sayonara by Unboxing Theatre

Choreographers and dancers Ami Nagano, Aqiong Zhang, Ching Chen and Yuya Sato of Unboxing Theatre ask “How do we say goodbye?” in Sayonara, taking influence from East Asian funeral traditions. Through a series of vignettes, moving in unison and then in clustered separation, the work encompassed expressions of intimate emotion, grief and ritual.

The cast, dressed in flowing back clothes, each held sticks that morphed in shape as they danced together, at one moment, forming a human figure that seemed to glide downstage before disappearing into abstraction like an apparition or memory. Their collective movement embodied a gestural and fluid quality that was both touching and otherworldly.

Sayonara symbolised a contact with the unknown and out of reach, brought to life through a series of sensitive and challenging physical encounters.

DOUBLE EDGED: Laboratory of Human Friction by Ka Ki Christina Lai and Ying-Yen Yvonne Wang

DOUBLE EDGED: Laboratory of Human Friction created a confined space in which dancers and choreographic collaborators, Ka Ki Christina Lai and Ying-Yen Yvonne Wang came head to head in conflict. In a theatrical performance that fused expressive contemporary dance with choreographed fight scenes, Lai and Wang explore the possibilities for reconciliation and bonding beyond difference. The piece was introduced by an AI generated voice, dictating the experiment: Two polar identities enter a behavioural laboratory to discover whether their differences could be the catalyst for connection or destruction, set to an epic sci-fi inspired soundtrack.

The themes explored in DOUBLE EDGED were at once futuristic and eerily current. When personal identities and appearances are compared, criticised and thrust into debate over social media, it seems only necessary that these topics are emerging subliminally, reflected in the work produced by emerging artists in the current contemporary dance scene. This piece reminded me of the pressure we all face to conform socially whilst embracing individuality, navigating the constant changes in the status quo on a tightrope.

Words by Florence Nicholls.

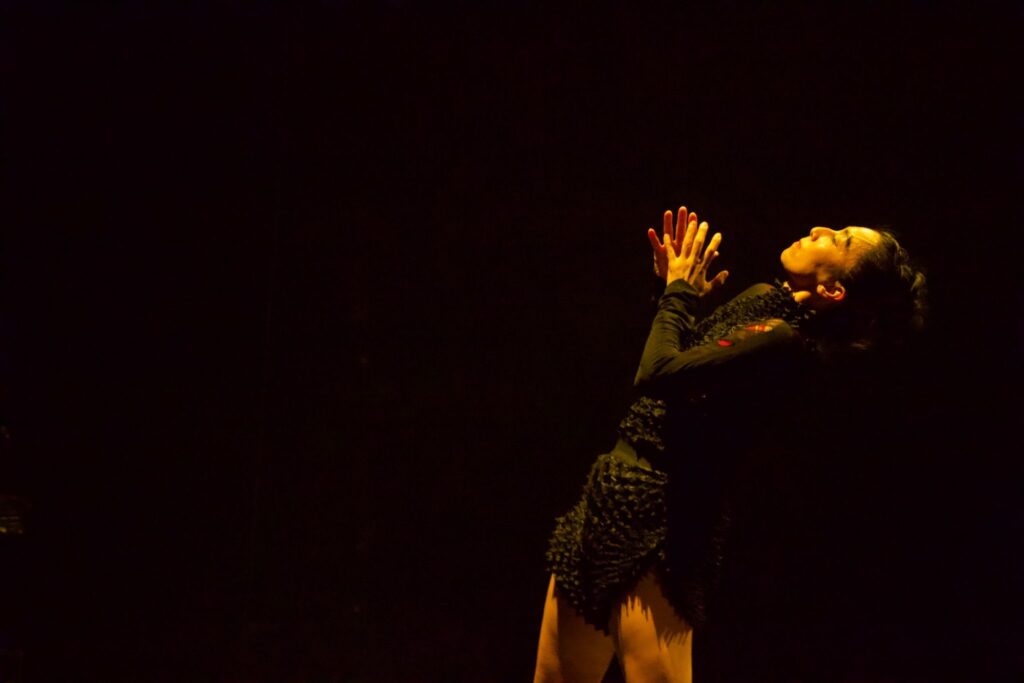

Invisible Chaos by Tomo Sone

With detailed clarity, choreographer and performer Tomo Sone opens her work with a highly stylised reverance – a bow to the audience – at once acknowledging the audience as observer and positioning themselves as subject of observation.

There’s a restlessness to Sone, a constant vibration under the skin. Tension builds through the contrast of virtuosic feats (high kicks, arabesques and impressive penchees) laid side by side with the tiniest detail of a movement or an obsessive twitching. The piece deals in extremes like this – quick/slow, large/small, start/stop.

Sone easily ricochets between total immersion in their own body and a performative sheen as they look out at the audience as if to say “Are you watching?” There’s an unsettling melancholy to that look, making one acutely aware of their position as observer. A recurring motif of extended, clasped arms stands out amongst the largely abstract choreography for its expressive quality.

The sort of chaos that exists under the surface like a background hum – the underlying tension, the unhappiness of constant observation and performance, moments of emotion rising to the surface – Sone’s work holds a magnifying glass and renders them visible.

When The Petals Fall by Yan Yin Yung

When The Petals Fall by Yan Yin Yung opens with the dancers clad in white robes, ghosts repeat and replay the tracks of their death. One trips and falls, one audibly struggles to breathe, another wails and cries. Almost like a wound that one pokes again and again, these ghosts revisit their lives and sadly struggle to move on.

Like lost souls (and it is, in fact, currently the month of the Chinese Hungry Ghost Festival at the time of writing), they sit around in states of inertia, hunched over and staring at nothing.

Moments from past lives where they once belonged appear – a childhood hand slapping game, a friendly duet, and a synchronised hand dance. Yet its constant repetition forces its mutation in the mind’s eye and one never returns to it the same.

Finally, the souls coalesce with a group dance to a thrumming beat as the stage turns pink. The final image sees the souls turn to look straight at the audience before a sudden blackout. Yan Yin Yung’s ghostly When The Petals Fall leaves the audience questioning: “What will the rest of their journey in the underworld look like?”

Words by Qiao Lin Tan.

Towards a New Architecture: Brutalism by Jiarong Yu and Neverland Space Theatre

Immovable blocks, straight lines and plain facades, or a soft flow imbued with counterbalance? What best embodies brutalist architecture? Jiarong Yu and Neverland Space Theatre deconstruct and then re-build the characteristics of this architectural style in Towards a New Architecture: Brutalism. The dancers move largely in sync, a strictly uniform entity echoing the heavy concrete structures – i.e. The Barbican – so popular in the UK during the 1950s and 60s.

Towards a New Architecture explores building something anew, but it also captures Brutalism’s raw essence. Group sections are co-choreographed by James Shing Mu CHENG, with a duet section co-choreographed by Zhe Zhang, making for subtle switches in movement style throughout. Inexpressive yet logical, practical yet pleasingly geometric, the eight dancers arc and loop through each other. One fist beats against another in steady correlation with the music. Linear line formations are favoured, and jagged angles and an insistence neatness punctuate clean gestures. Just as it feels safe to assume that Yu’s primary aim is to translate Brutalist aesthetics into dance, a more personable edge broaches the surface.

Drawing towards softness, a duet combines the harshness of brutalism with hints of emotion, the dancers acting as two oppositional forces with the tips of their toes pressing against each other as her feet push his, forcing him into a slow backwards walk. Hints of difficulty and disagreement seep through; she shakes her head rapidly against his hand, as if in despair. The duality here echoes the physical force of construction, alongside the vital human element in building anything new and inciting change.

By the time the dancers have regrouped at the end of the piece, forming a multilayered construction of their own, there is a sense of journey and resolution.

The Great Void by Dove Che

Dove Che’s The Great Void navigates an in-between space filled with sensuality and meditation. A duet between dancers Qi Song and Yos Clark sees the pair hang in perfect mirror images, arms held out like bird wings or torsos wound about each other. The simplicity of the piece – bare skin, a single white spotlight – transports us to a surreal world revolving around two bodies. With Song’s back to the audience, sat with her upper body inclined towards her knees and Clark leaning against her side, facing forwards, light and shadow entwine and confuse these bodies into an odd creature. My eyes finally adjust to make sense of tangled limbs, which pull apart and fold back constantly. Time is lost as the duo drop deeper into the void, a place of gentility and unknown possibility.

Each movement is breath-taking and carefully considered, and it is easy to imagine that the dancers are going through their own meditative process before they melt into the darkness. In the pauses, the feeling of coming to stillness is as natural as the movement that follows. Delving into Eastern thought on a Western stage presents a space for contemplation beyond the typical lives we lead in the UK. Collectively and unexpectedly then, The Great Void encourages the audience to slow down and pay attention to the smallest of details gradually unfolding on the stage in front of it.

Whilst the experience of a meditative atmosphere feels open to some extent, the dancers also generate an inward focus that extends towards almost every movement. There are moments when their internal concentration undeniably intensifies and makes the isolation vividly pronounced; Clark stands for an extensive period on one bent leg, the other reaching out behind him as his chest pulls forwards, or when both dancers roll and slide along the floor with their cores never losing physical connection. The result is an intrusion into something cryptic and private, inexplicable in broad daylight. Once the piece ends, it feels like waking from a deep slumber with a vague but peaceful recollection of a faraway dream. Haunting, quiet and deep, The Great Void offers a tranquil retreat into a hypnagogic state.

Words by Janejira Matthews.

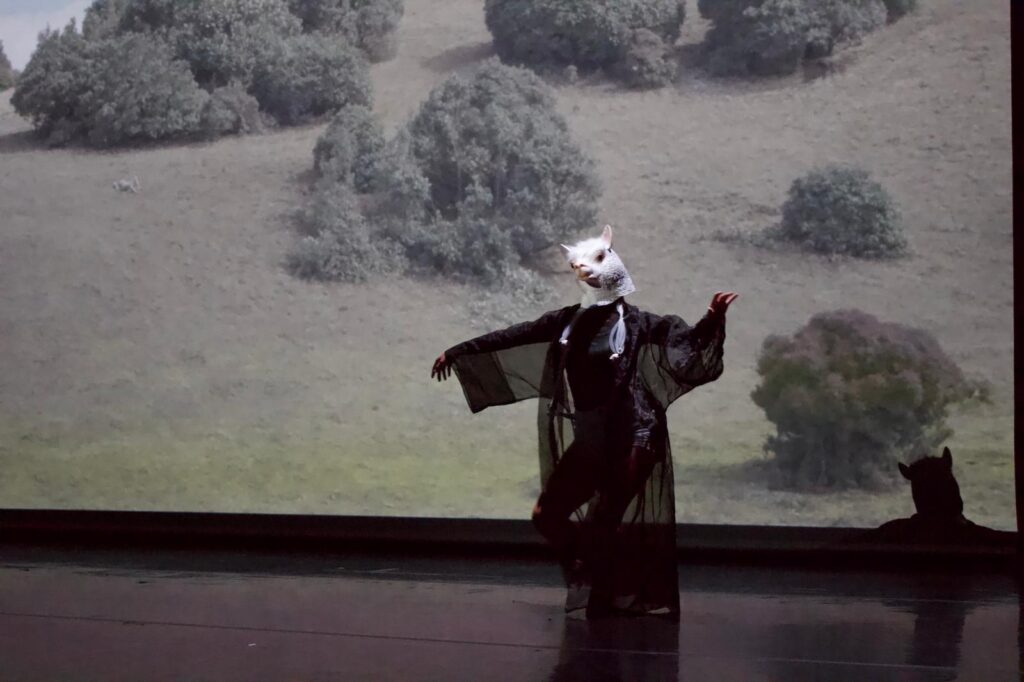

Black Sheep Reversal by Kiwi Chan

Kiwi Chan’s Black Sheep Reversal begins right up close to a woman’s face onscreen, the sound of the forest trees rustling in the wind. Our senses continue to be stirred when a gong chimes. A figure wearing a white sheep’s head enters, dressed in a black organza dress jacket that billows slightly as they walk. The figure moves suspensefully, laboriously, slowly, as if waiting for the end.

As the sheep moves in front of us, so does the woman in the forest projected onscreen. Although they both move similarly – meditative movements interspersed with phrases that are more frantic – we get the feeling that the person onstage isn’t quite moving to the same tune. Unexpectedly, the dancer onstage removes the sheep mask, revealing a woman’s face. At the same time, the screen goes blank and the woman disappears. As one reveals herself as the other disappears, are these two bodies connected?

Now, on a completely dark stage under a spotlight, the dancer swings two skeleton arms like a lasso. Seemingly twirling with death, the dancer straddles, arches and pumps her body; the tone of the work tipping between the macabre and the freaky.

Operatic music starts to play, as the dancer onstage spins sorrowfully, mournfully. The dancer backward-rolls eight times in a row, each time getting more difficult. The piece ends with a return to the screen, the woman now dressed in red jumping and scuffing her feet into terracotta sand, digging into her roots.

Throughout Black Sheep Reversal I was left wondering about the abstract relationship between the woman onstage and onscreen. With the help of the programme notes, I discovered that Black Sheep Reversal is based on ‘grass mud horse’, an internet phenomena used as symbolic defiance of censorship and control. In Mandarin, the term parodies the profanity ‘fuck your mother’. Knowing this, Black Sheep Reversal is all about a woman who doesn’t want to conform to the expectations set by her mother and her mothers before, choosing to wrestle with and break from tradition. If we bring Black Sheep Reversal into a broader context, it is a further comment on the perils of censorship, conformity and labelling of anything considered ‘unique’ as ‘abnormal’. Black Sheep Reversal is poignant, surprising, freaky and unearthly.

CHUM by Hahyun Kim

CHUM, choreographed by Hahyun Kim and danced by both Hahyun and Yerim Kim, takes the fan as a stimulus to show what happens when it is used as an extension of the body.

Slicing and angular contemporary movements to metronomic music are aplenty in CHUM. Arms cut into the performance space as legs stretch and sweep. Hahyun and Yerim dance in perfect synchronicity; each movement flowing and mutating into the next like lava in a lamp, only ceasing when the music stops.

CHUM takes its name from the Korean word for ‘dance’, and as an audience member (and as someone who dances), you get the feeling that the dancers have this ball of energy in their bodies that is generating the movement. One moment the ball moves to the tips of the fingers, next the torso and then the toes. And this ball just keeps on moving around the body spontaneously, venturing to places unexpected to awaken them. CHUM showcases how movement can be a site for the pursuit of authenticity in dance, highlighting the significance of moving in a way that feels good and is right for you.

Words by Katie Hagan.

Images by Rachel Gibson-Duff.