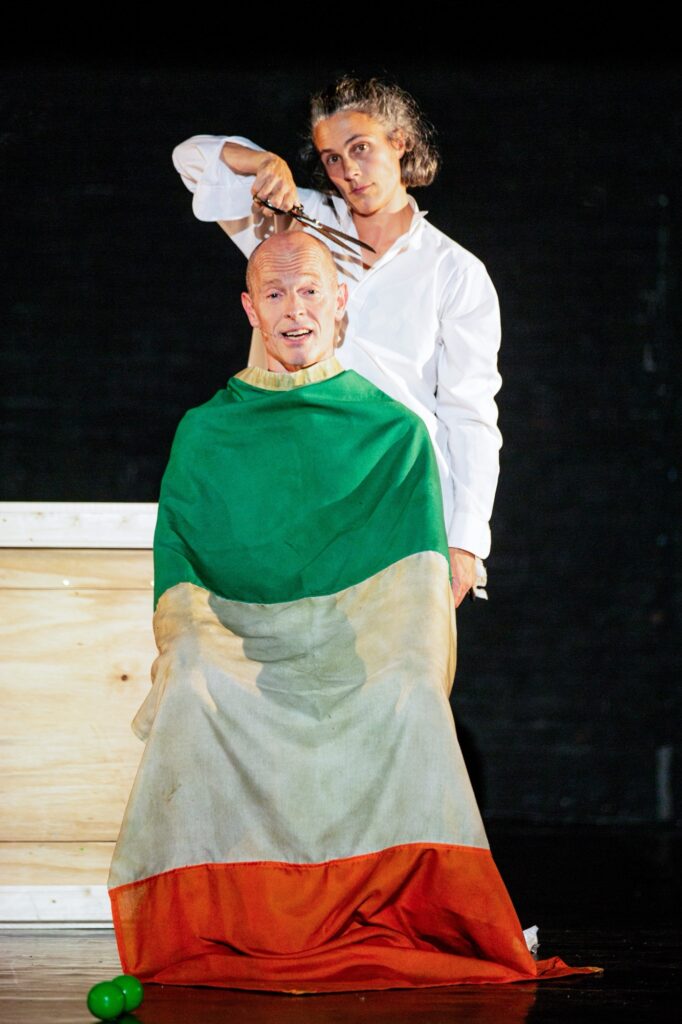

Michael Keegan-Dolan / Teac Damsa are known for creating works that draw on themes of identity, nationality, mortality and love to reflect on the human experience and our collective journeys.

This week from 17-20 September, Michael Keegan-Dolan / Teac Damsa bring How to be a Dancer in Seventy-two Thousand Easy Lessons to Sadler’s Wells.

We caught up with Michael to find out more.

Q: Tell us about your work How to be a Dancer in Seventy-two Thousand Easy Lessons.

A: It’s one hour and twenty-four minutes long. It makes people laugh and cry. It’s about duality and a journey, marked by defining situations and negotiations that ultimately lead to a place of temporary resolution and the associated peace and equilibrium.

Q: Why did it feel important to create a coming of age story?

A: It didn’t feel important. The overwhelming sensation while writing it, creating, and rehearsing it was a burgeoning feeling of how unimportant so many of the events that we think define us truly are. And how one can eventually become free of their influence through a process of disciplined reflection, experience, and sensation.

Q: How do you navigate Ireland’s complex history through dance, spoken word and physical comedy?

A: I didn’t consider any necessity to navigate the nation’s history in the creative act of making How to be a Dancer…. Instead, I turned inward and observed which stories, myths, and hard historical realities, spoken and unspoken, told and untold, had impacted on my being and all its layers: physical, mental, and spiritual. That was more than enough, without having to also unpack thousands of years of history.

Q: What does it mean to be Irish?

A: Academics, historians, and social commentators have written hundreds of books around this subject, some of which are 500 pages long.

All I can comment on here, in this short exchange, is that I first began to consider what it meant to be Irish when I moved to London in 1988 to study Classical Ballet. Margaret Thatcher was at large and the IRA was bombing England. Inside the ballet school walls I was subjected to the accepted body-mind-separating politics of mirrors, lines and the aesthetics of the Classical Ballet world, where my female colleagues were weighed like racehorses each Monday morning. Outside those walls, while working in various public houses to make some money for food and rent and so forth, I experienced a regular stream of xenophobic comments, mostly along the same theme, usually being called, ‘ a fuckin paddy’,by complete strangers for no reason. The theme of me being Irish and, for some reason, also drunk, stupid and hyper-emotional, was also explored in my presence by the same strangers. This obviously began a process of self-study, which intensified when I decided to move back to Ireland in 2003.

In later years, returning to London as a choreographer, the soft and sometimes not-so-soft xenophobia continued, but now in the form of reviews of my work, with casual references to my drunkenness, my hobnail boots, Father Ted and describing a song sung in Irish, as sounding like someone ‘speaking in tongues,’ etc. I could go on…

There has clearly been a long and complicated history between Ireland and England, the lowest point being the Famine of 1845-50, which many historians agree was unlike any other famine in the history of Western Europe. Between one and two million people starved to death and another two million emigrated during and after the famine. These people were all indigenous Irish people but at the same time were subjects of Queen Victoria.

They were allowed to starve as huge quantities of food left Ireland for England. Incoming aid was controlled closely by the government so as not to negatively influence the price of wheat and barley on international markets. In many cases, lifesaving soup was only made available if people were willing to change their religion from Catholicism to Protestantism. The Quakers were one of a few organisations that made heroic and sustained efforts to help the starving Irish.

I think the collective memory of the Famine in Ireland is one of the reasons why so many Irish people today are unwilling to stay silent about the man-made starvation of hundreds of thousands of innocents, non-combatants, women and children in Gaza.

For me to be Irish means having a strong connection with people. Friendliness and curiosity are primary. Welcoming the stranger is fundamental. A respect for nature and the power of the imagination.

A capacity to endure and survive incredible hardship. A toughness. A willingness to forgive and move onward.

Q: What’s next for you?

A: I am going to my niece Kate’s wedding in Tuscany. She is a highly regarded film director and writer and she is marrying her long-time partner, Ciara. I can’t wait.

Visit here to book your ticket.