Words by Georgia Howlett.

King O’Holi prefers to stay in the background, but this hasn’t stopped him from working with household names as a movement director and performance mentor. Whether King’s name is familiar or not, you have likely seen his choreography on screen, or in arenas as mighty as the 02 and The Royal Albert Hall. King is also the founder of two thriving hubs, Space to Create (STC) and STC Training Club, the former for artist mentorship, the latter for young dancers keen to drill down on their technique and develop their artistry in a safe, community led space.

In our conversation last month, King describes Space to Create, his agency for choreography, artist development, casting and performance direction, as a “house of creatives”. Though clearly a successful choreographer, King seems to find the most reward in mentorship. An in-depth, artist first approach prioritises connecting with the artists, mainly singers, as people first and foremost, to work out “who they are, how they feel and what they want to share”. Many of the artists King works with are not dancers, or at least don’t choreograph; STC therefore supports them with artistry as a whole, from how to authentically share their stories, to their stage presence.

King often finds himself “side of stage with a microphone and speaking to the artist while they’re performing, giving them a little bit of direction and energy”, thus the mentorship extends to a performer’s communication with a crowd. STC is therefore not merely a choreographic service, but a holistic exploration of artistry in all of its facets, and a commitment to an artist’s journey in self-expression.

Some big names have travelled through STC, Little Mix and Sugababes to name a few, but King is equally invested in the next generation. Every Saturday, hundreds of members flock to the STC Training Club; just last month, the club took on 221 members following their third audition season. At the root of STC and STC Training Club are spaces designed for artists to identify who they are and “continue moving into their most authentic self.” And yet this isn’t just about the studios; Training Club takes place at LMA University at Here East, though King hopes to soon have his own base. Instead, it is King’s approach to facilitation that creates an environment in which creativity flourishes and genuine connections can form.

The right space can go a long way in nourishing a young dancer. Although a foundation in dance is expected of those who audition, and the training is no doubt high quality, the Training Club is not solely for dancers who intend to pursue a professional career. It is refreshing to hear of a studio where a certain level of vigour is provided, an array of educators are brought in to teach, and yet a specific outcome is not expected. In King’s words, “it’s a space where we like to give people the tools and knowledge to then potentially go into the industry.” A sense of community matters above all, and one where young people can identify their creative path and desires, whether it is in dance or not. “There’s so many friendship groups that have been birthed at STC which is one of the biggest things that I can take away from this thing that we’ve created because I think collaboration and connection, especially in this day and age, are so important.”

STC Training Club endeavours to make training less of a space of competition and pressure, and instead one of discovery, bonding and, well, good vibes. Recently, the Royal Ballet School announced they would no longer provide full time training for dancers below the age of 12, a decision acknowledging that intensive vocational dance training at a young age can often do more harm than good. Though ballet and its specific training regimes are removed from the afro styles in which King found his love for movement, this news formed the context in which to ask him about starting his training at the not-so-ripe age (in dance terms) of 21. It was at this age that he joined The Hip Drop, a centre ran by Lin Samuelson in Sweden, and was exposed to the dozens of choreographers Samuelson brought in from LA.

King agrees that a late start allowed him to enter training in a more grounded way, and though some may say that the feeling of needing to catch up with other dancer’s fuels comparison, King does not regret the journey he has had. He instead channelled his energy into a clearly defined goal: to get on to the stage, not worrying about what others thought along the way. Besides, Kings love for dance actually began over a decade earlier, when watching and copying music videos as a 10 year old. “Dance has always just been a sense of freedom. I lost my mum at a young age and dance was something that allowed me to get through those times, which is why I always had such a big love for it.”

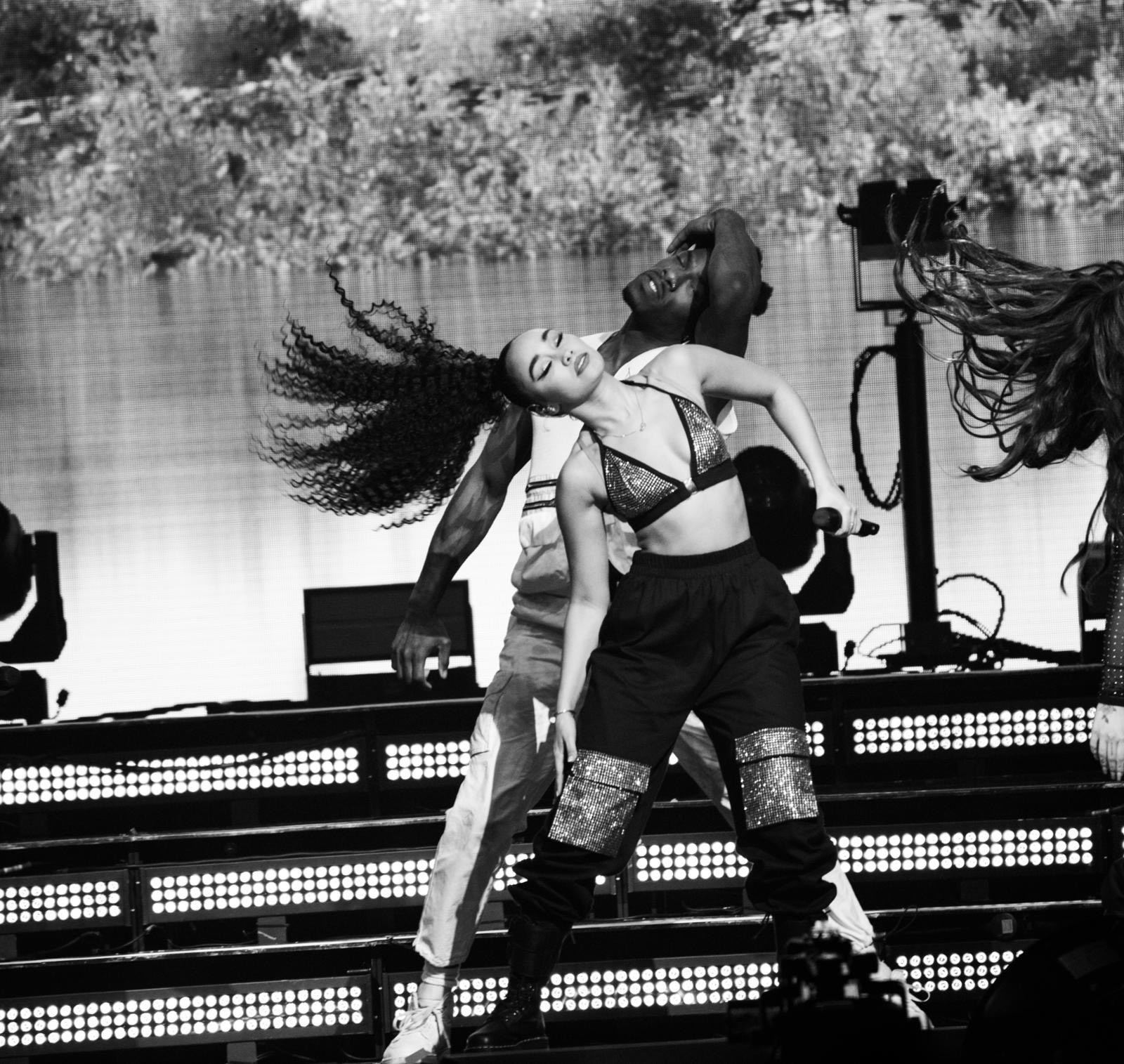

Staying behind the scenes has perhaps been essential to STC’s approach to mentorship, which puts the artist first. It is not surprising, then, that for King, sharing on social media feels forced. Instagram often feels like the modern day CV and is deemed a fruitful place to connect and collaborate today, as well as to attract opportunities. That said, King hasn’t needed to rely on social media to get his name out there. From his first dance job as a backing dancer for Jess Glynne, to choreographing for Clean Bandit and performance directing for J Hus, his impressive career is the result of organic word of mouth.

King is working on being more present online. His wider goals, however, concern his wellbeing. When asked what’s next for someone on such an upward trajectory King says, “I’m just trying internally to better myself every single day. I know, that may sound cliché, but I just think in order to achieve the things that I personally want to achieve, I have to be operating from a place of just like optimum health, and good well-being. So, the top of my wish list right now is just an abundance of health and good energy, so that my manifestations can become a reality.” Although burnout is oftentimes the reality of an artist moving through today’s dance sector, this is a reminder that self-care can be a starting point, and not only an afterthought, that maintenanceis a worthy goal and staying still is not regressive.

For King, a key moment of learning involved realising that working sustainably meant not sacrificing energy to a room where it wasn’t being reciprocated. “I learnt to how to step onto a project and match the energy of the team, still always delivering a service that I know is authentically me and special. It was just a way for me not to burnout.” Collaboration, too, can help sustain and inspire artists in todays challenged dance sector: “A lot of dancers or creatives just don’t realise that there’s no one-man island and there’s such a power in just team and a unit. I think you can go so much further and create so much more longevity collaborating as opposed to trying to do everything by yourself.”

In operating in the background, King is after all, being himself; doing what he loves in a way that feels honest. To King, a successful artist is one who can express authentically, an honesty that begins before the movement has been created, and hopefully lingers after a performance too. He asks, “What is the purpose of this dance? What are we trying to say, and ultimately, what is our intention? If we are performing to an audience that has no idea about dance or the technicality of dance the first thing that they need to do is feel it.” It is the storytelling that matters to King most, regardless of the specifics of the steps. After all, his choreography spans many styles and stages.

So, what are King’s manifestations? He wishes for Space to Create to have a home base, “a foundation where we can continue to inspire not just dancers in the community and creatives, but also all the artists that we that we work with and just the wider community in general.” King’s thinking clearly extends beyond training and performance, considering what dancers can benefit from beyond a safe studio, such as a kid’s area, to relax whether they take class or not.

As youth services fold and arts centres struggle for provision, King’s desires for the younger generation are both pertinent and hopeful. “I think about what makes a good mentor. Patience and passion come to mind, but in speaking to King, so does devotion. He is committed to the evolution of every artist he works with, whatever form that may take. Equally, with every successful name King is associated with, there is also a genuine desire to invest what he has learned from such experiences back into London’s diverse community of young, creative talent, from dancers to singers and every performer in between.

Find out more about King O’Holi here.