Words by Saskia Horton. This article is part of our REWRITE series with Chisenhale Dance Space’s Artist Community.

It’s so hard to understand systemically or literally what anti-ableism is in the dance world (and beyond) because so few people understand what ableism actually is. We understand racism and sexism – even if vaguely or historically – as discrimination against people of marginalised races or genders. But even as multi-billion pound benefits cuts threaten to destabilise the lives of disabled people across the nation, language and rhetoric of disabled people as lazy, benefit scroungers or undeserving of support and cheating the system are rampant.

This is because ableism is the bedrock of capitalism, and capitalism positions us as only being worthy insomuch as we can work and contribute. And although disabled people might not always contribute financially – even though actually a lot of us still have to work even on benefits! – the richness of our lived experiences, approaches to vulnerability and ability to empathise across barriers and understand differences, means we are great at community building, leveraging support and networks of solidarity. A skill that is going to be tantamount to the survival of everyone (pretty soon) in a late-stage-capitalism-climate-change apocalypse. To add to that we will all come into contact with disability at some point if we are lucky to live long enough, or due to accident or illness. So this isn’t an issue that just affects 25% of the world’s population, it affects us all.

Many facets of the dance and arts industry compound ableism in the way we train our bodies to such a degree – to be harder, better, faster, stronger. Often also adhering to white supremacist, ableist, fatphobic body standards. And while dancers see themselves as super-human auteurs of our own body-minds, the industry, due to oversaturation and competition, sees us as disposable bodies, breakable bodies. Not as bodies requiring care, softness or community, but machines to be mined for profit and, in the name of capitalist efficiency, in need of conformity and control.

Perfectionism, pervasive in most professional dance spheres, polices a lot of disabled people, whose glorious wonky bodies do not fit. So what happens when you simply can’t conform to a dance style’s rigorous technique due to a wobbly body, rising blood pressure, limb difference or an inability to stand upright? What diversity do we lose and whose stories are not told? Surely, there is no ‘right or wrong’ way to ‘be’ as dance is expression and creativity in motion. But ableism and conformity causes us to lose sight of that.

The truth of disability is that it points out our inherent vulnerabilities, our weaknesses, our mortality. Even our own death. And we live in a society that is terrified of death. ‘Fear of the unknown’ is the dark underbelly of a society obsessed with control and domination. And to someone who hasn’t previously been disabled or had disabled people in their life, disability is one of the biggest unknowns.

Lived experience

In 2019 I saw a short film about someone who was living with my condition before I was diagnosed. The inherent fear and disgust I felt was full-bodied. I couldn’t imagine living like that. Me turning away from her lived experience was instinctive. An existence where I didn’t capitulate my entire self-worth on my ability to ‘do’ dance or to create art was a reality I couldn’t imagine. I didn’t want to.

Because I conflated loss of ability with a loss of self.

So when I woke up one day and couldn’t move, all the illusions of my old life fell away. The things I thought I held most dear, along with my functioning body, slowly dissipated. I fell into this comfortable lull or reverie. I realised the darkness was bliss. I experienced something akin to death – maybe not real death but being very close to it. Or perhaps death in the metaphorical sense? An ego death?

The feeling that my old self no longer existed. And I didn’t need to be anyone or do anything or show up in any way. I could just… exist and that was enough. Disability actually reduced me to my purest form of self and self-understanding. I learned to love myself from the ground up. With no expectations, external pressures, alternate realities or unhealthy relationships. It simply all fell away.

‘Disablement’

The way we view disability is largely due to attitudes in society, perpetuated by stereotypes in the media that contribute to larger socio-cultural narratives around disability. These attitudes can be categorised into the ‘Models of Disability’. There are many, and there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way to view disability, although some are mostly preferred by disabled people over others.

The ‘Medical Model of Disability’ for example states that we are inherently disabled BY our illness and/or impairment, which is something that needs to be fixed, cured and labelled as such with a diagnosis. Whereas the ‘Social Model of Disability’ suggests that we are disabled by an ableist society – a society that doesn’t cater for us. And it is in fact the lack of education and social barriers that renders us disabled. In this way it is pointing out that there is no binary between disabled and non-disabled people. But rather the polarity exists between being disabled and being enabled. In that way disability becomes a verb – a thing that we do to each other.

In relation to the social model, one thing I am examining as I get deeper into my anti-ableist practice is understanding the way in which we are also actively disabled BY systems of oppression. It’s what we’d call ‘Disablement’. It speaks to how people who are multiply-marginalised bear the brunt of racism, classism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia experience on an emotional, physical even maybe somatic and sensory level. Whilst policies on the state level politicise them out of the dominant social narrative. It speaks to how experiencing a lifetime of racism IS disabling- mentally and physically. How growing up in poverty is disabling, contributing to your immune health or lack thereof. Microaggressions over time, lack of access to medication, treatment or healthy food, working 40 hr + weeks and two other side hustles on top of it, pushes us to the brink of exhaustion until we literally can’t get back up. Resulting in disability.

It’s why 78% of people with autoimmune conditions are women (we internalise our pain, rage and anger to accommodate until it manifests as illness), it’s why heart disease and heart attacks are much more likely in BIPOC communities (microaggression and hate-speech chip away at arteries, oxygenation and blood flow), and why the mortality rates in the pandemic were much higher among hispanic frontline workers.

Through all of these systems of top-down hierarchy and control there are direct results in bodily outcomes and personal autonomy. It creates a culture where rather than listening to what the body is telling us, we ignore it and soldier on to our detriment.

But what if we did listen? What if we took accountability, not just for ourselves and our own health, but each other? If we slowed down enough to question the systems brutalising and beating us into submission, I wonder what our tissues might say? What our cells might whisper? That if there’s something wrong on the micro that communicates something about society on the macro? As Indian philosopher – Krishnamurti said:

“It is no measure of wellbeing to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society”

Methods of survival

But as I said, disabled people certainly know how to survive. Disabled people are some of the most ingenious, committed, rigorous, creative, caring, interconnected people I know. We understand at the root of our very being that we cannot survive alone, nor would we ever dare to. The actuality of what becoming disabled does, I think, is that it brings you closer to your vulnerability – your needing to rely on others, and ultimately your humanity than being able bodied ever could.

Which is perhaps where the core of dance ACTUALLY came from. The ancient moving, grooving and shaking of our ancestors. Ritualistic and communal. Dancing used to be ALL ABOUT listening. Listening to the heartbeat, the alignment of our own body-rhythm with the seasons, building community through dance, telling stories and sometimes even transcending the body to connect with some higher power or spirituality all together.

When I worked as access coordinator for the company Yewande 103 on their show Many Lifetimes last summer, I worked one-on-one with the incredible Greta Mendez who in her many years as a professional dancer (the first Black female ballet dancer to join Scottish Ballet in 1979!) had much wisdom to share. Especially in the way of dance as storytelling, dance as medicine and dance as history. In one anecdote, she shared about the migration patterns of wolves and how the pack organises itself around the elderly, sick, mothers and children. Here is what she shared:

“In the wolf pack formation, the first three are the old or sick. They give the pace to the entire pack. If it was the other way round, they would be left behind, losing contact with the pack. In the case of an ambush, they would be sacrificed.

“Then come five strong ones, the front line. In the center are the women and children then the five strongest following after that.

“The pack moves according to the elder’s pace and helps each other, watches each other.”

This prompted me to come up with the phrase in the process: “We move at the pace of the slowest person”. Perhaps not always meaning literal speed of slowness and moving in that way. But we move at the pace of the person who needs the most processing time, who needs extra time to stretch, who cannot move as fast or download as quickly. And what would society look like if we moved in this way overall? Prioritising slowness, care, listening and watching over each other. Instead of speed, power and efficiency?

Shifting attitudes and conditions for survival

I think shifting attitudes towards disabled people have to come on a communal and interpersonal level. Because it is exactly the way in which capitalism has trickled down into community and our ideals, meaning that we have forgotten on a fundamental level how to hold. Rather than look at the person struggling with pity, loss, grief, are you able to move to act? Redistributing resources and support without question; offering to carry that person’s bag or giving them a seat; asking how you can financially support that friend who’s benefits have been taken away; or providing a space for someone to be really listened to, rather than telling them to go to therapy.

Paradigms of care need to be nurtured within ourselves as well. Self-empathy, self-compassion, forgiveness, re-parenting and nurturance. We can also seek advice from outside ourselves from trusted people and chosen family and our interpersonal support networks. Because as systems of care are disintegrating, we may be looking at a future with: Less/limited free healthcare, access to education, housing, third spaces and nature.

What conditions do we NEED to create in order to allow us all; disabled and non-disabled to survive? How might developing these attitudes contribute to a culture of anti-ableism? And how do we need to come together to ensure the crumbling of these systems don’t further disable us?

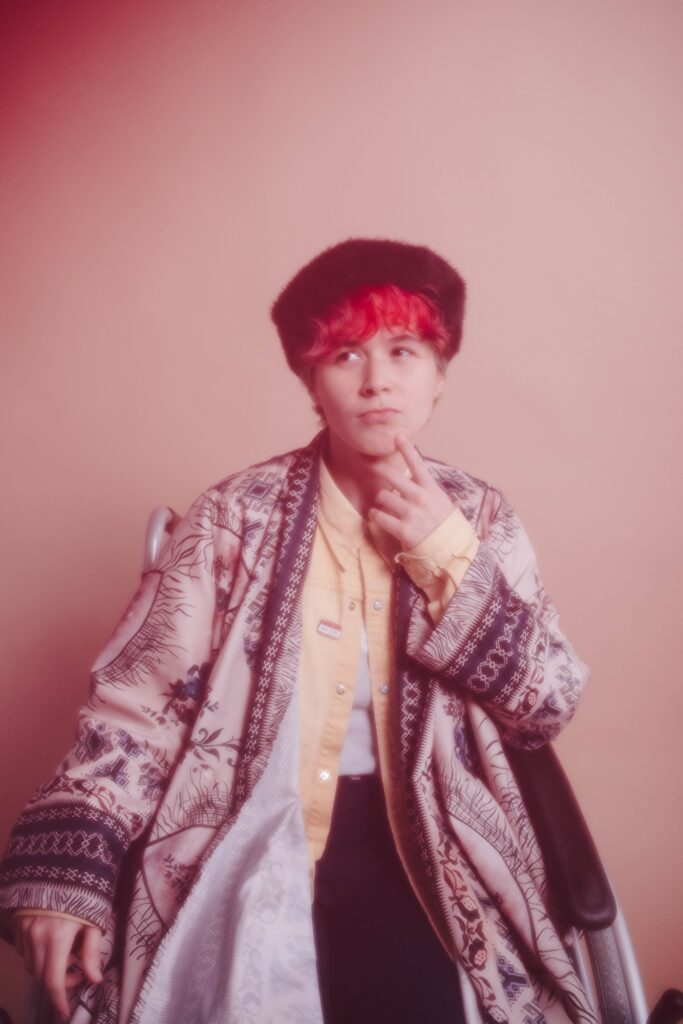

Header image description: Saskia, a white-malay nonbinary person with a blue mullet sits leaning forward in their wheelchair in front of a brick wall and sign in multi-coloured letters that reads ‘Welcome to OUR HOUSE’.