Words by Maxine Flasher-Duzgunes.

Dance Art Journal shared a conversation with choreographer Becky Namgauds ahead of the London premiere of her work THE HEAT at the Lilian Baylis Studio at Sadler’s Wells on Thursday 22 and Friday 23 May and at Quays Theatre at The Lowry on Tuesday 3 June.

Maxine: As a choreographer, what drew you to dance theatre as the defining genre of this particular work?

Becky: I’m always quite cautious around labeling work to be something specific, because then you feel a bit trapped in a box. But for me, I think dance theatre explains it best. And I think because I have a lot of influences from many different sorts of art practices, that it really shapes the work in that way. Beforehand, I was doing a lot of work that was really about the physicality of the body. And it still is in a way, but I was heavily focused on choreography and it being just about the dance. I don’t know how it happened, but I’ve always been really interested in bringing in multiple disciplines. I remember discovering performance art when I was 18. The first piece that I made was set in a half a ton of soil, and it was an outdoor work. I really enjoyed working with other elements and I guess this was the first time I worked with real set design as well.

For THE HEAT, I wanted to work with an ensemble. I love the work of different artists who manage to bring a high physicality to the stage, but also really intricate and naturalistic movement, and often have a relationship with objects on stage. And I really enjoy the challenge, the sort of fleshing out, the mixing and then unpacking of all of these layers. I think there’s just something really interesting for me, that is about seeing and – specifically for this work that we’re doing – feeling like a real place, and for it to be totally relatable for people. The set design that we have is a living room (and it’s so much nicer than my living room), so in some ways, we can all relate to it.

Maxine: In your creation of the work, how did you and your collaborators consider the scenic elements in amplifying the idea of a domestic space?

I had the Time and Space Commission at Sadler’s Wells, where they give you funding and two weeks of space to basically do what you want to develop your practice without having to have an outcome, which is very rare. I’d been thinking about this piece, and obviously wanted to work with set design, and I hadn’t done that before, where we work with furniture from the beginning of the process. It was really important for me, because the work that I was imagining was a lot about the relationship of the space and the performers, and bending the reality of the space. We just had a sofa, a door, and some stairs. And there was a production designer named Solene Riff that I worked with that week who brought in this plexiglass fish tank that we filled with water and played around with, so some of the physical ideas came from that. Those two weeks were actually really important for me to find a way to move the process forward, because it was great to have space where we didn’t have to show anything, and that meant that we could just take all of the risks that we wanted.

A few months later, we were at South East Dance, and we literally just stole all of the furniture from the dressing room and didn’t tell them, but they were so kind about it. In the sharing, they were just like, Oh, you’ve got all of our furniture. Okay, great, let’s go with it! They were very generous. We’re also trying to be very green and not waste materials where possible, and it’s really important to do that, but at the same time, we’re restricted by our own budgets and resources. When I found this great set designer named Yimei Zhao, we had a few initial ideas that we were really excited about, but then when we applied for our funding, I was like, Okay, this is not possible. You need to rethink. That’s been developed a fair few times, as we had to be a lot more flexible for traveling, because we really want to tour the work.

I’d spoken to Yimei about this domestic space, and that it feels feminine and soft and full of textures, and that there’s something off kilter about it that you recognize. The first idea that she came back to me with was this one room, but it had all of the rooms, like there was the fridge, there was a shower, there was the floor that was tiled like a bathroom, and there was the sofa and rugs, and everything was really stunning. And then as we developed more ideas for the work and more scenes, we brought it back down to just it being this living room space. Without saying too much, we really tried to not let the fact that we were working with a set also restrict us to only work in the set design as well.

I was really interested in exploring illusions, and that has informed what Yimei created: we have a five meter curtain that hangs in the space, and then we have carpet and a sofa and some other objects. There’s some stage magic or theater illusions, and I’m really interested in doing it in a way that’s not like, here’s a magic trick!, but to incorporate it so that it feels seamless within the choreography. Early on in my career, I was in a show called Angels in America at the National Theatre and we were doing puppetry and movement within it, but we had to do many other other roles too. There was this illusionist who would come work with us, and he was making people disappear on stage, so I got excited. And I was thinking for a long time, like wow, just imagine working with people who have got that control of their bodies, to be able to merge with this great control of lighting and use of props. It’s something that I’d love to be able to develop further with time and space.

Maxine: Can you speak about your desire to work with an all-female and intergenerational cast, and the importance it poses in the world today?

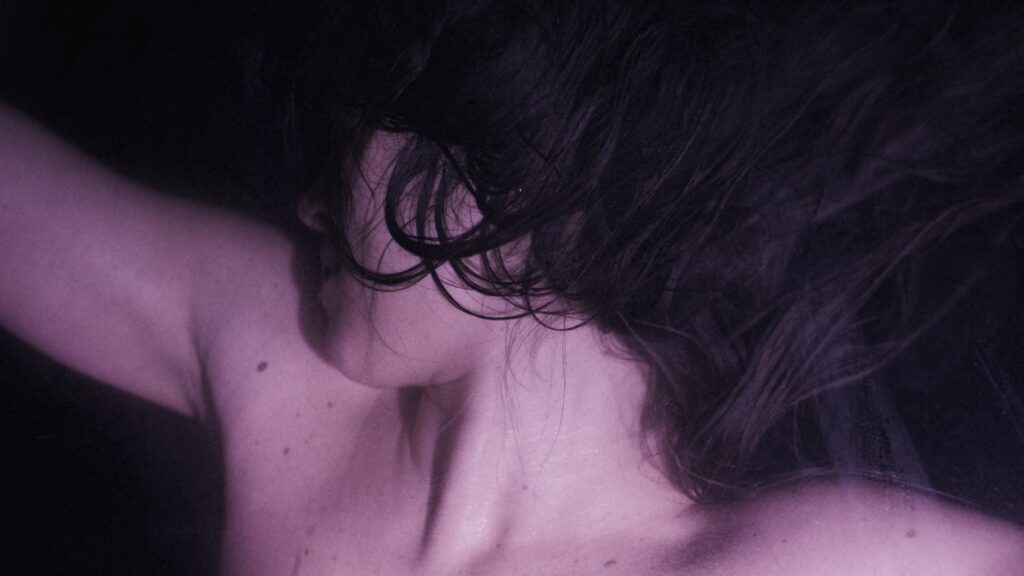

Becky: There’s a quote from Marguerite Duras, who said of her work or any woman artist, that they are translating darkness. And for me, this explains what we’re trying to do in this piece, because there’s so many things about womanhood or being socialised female, or like the relationship of people who identify as women and the domestic space that are not huge issues. These can be minuscule things, everyday things that we live with that aren’t necessarily talked about or represented, and I guess that they feed into some bigger questions that are related to the themes of the work.

I also like to work with women because there’s so many women in the industry. Whilst there’s room for improvement, like all the time in terms of representation on stage, I just think that first, seeing a group of women of different ages exploring similar subjects and not necessarily being separated is interesting. And also, to develop work with those people and hear their different perspectives, cultural backgrounds as well as their relationships with desire and food and sensuality and the space itself – I think all of that’s really valuable.

Whilst I wouldn’t want to pander or dilute work in any way for a specific audience, I also think that there’s a lot of work to be done in terms of making dance, theater and feminism accessible to people and to find different ways of discussing and representing people. Also, I just love women. I love working with them. It doesn’t mean it’s easy and straightforward. But there are so many women, overlooked. I work as a guest teacher in conservatoires here, and I think it’s still something that has to be reckoned with majorly, in terms of women being given the same chances because of unconscious bias. To try and keep on uplifting each other, it’s quite important to my work, and to the process as well, to find people who are comfortable with sharing parts of themselves and being vulnerable, and sometimes that’s just a bit easier to do when we’re talking about the shared experience.

Maxine: How have you worked with being “primal” in the development of your choreography?

Becky: When you hear the word in relation to movement, you can easily think of this low center of gravity movement. And I think that that’s part of it, and that’s valuable, but when I first got the idea for the work, I’d been taken to see these paintings of Paula Rego called Dog Woman. There was a series of them, and they were women literally depicted as dogs in domestic spaces. The way that she always depicts women is chunky, muscular, and stocky, and I loved that, because I saw myself in those pictures. And they’re dressed in these delicate, lacy garments, what you’d imagine a housewife to wear in that era. But they’re on their hands and knees, crawling or growling and snarling. And she talked about those paintings, saying that it wasn’t about depicting them to be downtrodden, but it was just about them leaning into the senses and feeling. And that’s kind of how we approach the work. It’s a lot about touch, and feeling the set, and then exploring, like we have a scene in there with eating, and there’s a scene that is more about horniness, and how to explore that when it’s not really in relation to anyone else. It’s about following sensation and thinking about life, or what you would do if you could drop away all of the myths of what you should be doing in life, and do the things that we as animals are supposed to be doing.

I guess the work is performative, but we’re always trying to explore something that doesn’t feel like it’s being performed for someone. So there is a tension in how you explore that real feeling, but at the same time know you’re being watched, but at the same time drop the idea that you’re being watched. To come back to the idea of primalness, it’s like trying to remove the internalized male gaze, which allows us to be ‘ugly’, or just not to have any external eye watching yourself. This is a thread that I’ve always been trying to explore. And I think that this is also why it’s so interesting to work with people of different ages and how we understand that for some people – it doesn’t matter who you are, that internal gaze is still with you somewhere, and we experience it in different ways, at different moments. Dancing itself is a primal thing. It’s a birthright. And it doesn’t belong to anyone.

To learn more about Becky’s work, visit her website at www.beckynamgauds.com and follow her on Instagram at @beckynamgauds.