Words by Francesca Matthys. This article is part of our REWRITE series with Chisenhale Dance Space’s Artist Community.

“I enjoy it when people feel okay to be held accountable” says dance artist Cherilyn Albert. We are speaking about anti-racism and we are talking between screens. Cherilyn is in the UK and I am in South Africa; a cross continental conversation in two countries that hold their own very distinct histories of racism in the past and present.

I had conversations with two other artists, Jose Funnell and Angela Andrew, on this topic. As a South African myself, I have a very distinct perception of racism due to my country’s complex past. This, amongst other things, can make it feel like we have been fighting against issues of racism and discrimination for all of time.

Yes, there is progress (I’m thinking artist-led spaces that create space for diverse voices to be heard and platforms specifically for BIPOC artists), but the residue of racism is often so much more detrimental, stifling and ultimately traumatic for communities.

In 2024 a new report using census data to map the arts culture and heritage workforce across England, Wales and Northern Ireland found that the industry was 90% white. That is the reality. A reality that is reflected in the lack of representation of non-white bodies on dance stages and leadership roles within dance.

This feels like an uphill battle and as a minority artist in London I am so conscious of often being the only or one of few BIPOC in the work environment, with limited effort made to understand this positionality. Optimism, however, reminds me of the many BIPOC artists cultivating safe spaces, in direct conversation with arts organisations, to change or at least make progress.

Inquiry

There are four aspects I would like to touch on in this piece as they naturally intertwine; art practice, organisations & leadership and legacy. Questions that I’d like to look at include: How do various embodied practices create space or become containers for anti-racism to emerge and be cultivated? What are current leadership structures within dance organisations and are they representative of true diversity, and marginalised individuals?What responsibility should organisations take in this work and what is the legacy of anti-racist work and its impact for generations to come?

‘Anti-racism’ can be summarised as a proactive approach that aims to dismantle systems that perpetuate racism. Over the years, particularly compounded by the Black Lives Matters movement, more and more attention has turned to anti-racism and the work that arts and dance organisations need to do to take down systems of oppression. And many organisations have done the work, to varying degrees.

There is often a large responsibility placed on BIPOC artists entering into organisations to be the ones responsible for solving all issues of racism…

Cherilyn Albert prefers institutions that go out of their way to say they’re anti-racist. “I think if an organisation is going out of their way to say what they are doing is anti-racist,” begins Cherilyn, “to me it shows a lot of intention and that they are willing to be under scrutiny.”

“‘Are they anti-racist?’ is not my first thought as an artist when I am working with an organisation”, continues Cherilyn, “and that’s probably because I put myself in spaces where I feel I align anyway. I don’t put myself in spaces where I won’t be safe. But when they say they’re actively being anti-racist, I immediately have questions in my head. Are they doing work that is continuous? It’s not that they can spend a season on it and then it’s done….”

Both racism and so-called anti-racism often find themselves camouflaged in deceptive ways, specifically racism that as Jose Funnell highlights is always “coded in ways that I can’t always name.” In my personal experience, it’s really easy to almost convince yourself that certain problematic behaviour towards you is not due to racism – regardless of the reality of racial inequalities present.

In the same breath, so-called anti-racism actions by organisations can also be present through diversity hires that don’t truly care for the lived experience of the person taking on a role.

I wonder about this age-long, conscious act of having to be aware of which spaces are safe for BIPOC artists and which are not, and the extra psychological and emotional capacity to discern this. As if trying to exist as an artist in our current economic landscape is not challenging enough!

There is often a large responsibility placed on BIPOC artists entering into organisations to be the ones responsible for solving all issues of racism, finding solutions and being the face of this narrative. Many artists are aware that organisations see anti-racism as a tick-box exercise rather than an active and current piece of work.

As an interviewer for this article, I myself felt very conflicted asking specifically black artists what could be done by organisations; holding the awareness that once again we were shifting the weight of this responsibility to the people living its effects. In the same breath, who else would accurately know the direness and what it feels like, while offering multiple and topical ways to approach a topic such as this?

Art practice

East End London-based Angela Andrew has been a dance artist for 30 years and has roots in Lindy Hop. Angela’s practice of awareness, questioning and responsiveness towards our own actions is an illuminating offering within this dialogue. Through her practice, Angela displays a practical and tangible tool for how we may be present to our own bias and perspectives. “How do we recover from our responses and our actions?”, says Angela. “It’s about character and values. Your values need to align with your actions.”

Angela recalls being confronted in St Petersburg by active discrimination in a predominantly white space. Her assertion of her right to exist as a black woman is a reflection of the active role she takes in her life and of which responses she chooses to assert at a particular time.

Within dance alone there is an abundance of practices that come from racialised people who over time have healed themselves and their communities. Embodied practices such as yoga and meditation alongside dance practices such as Lindy Hop and street dance have offered a strong presence in the writing of this piece. Yoga’s origins can be traced back to Northern India, though it has very much been colonised over time. Lindy Hop rose out of systemic racism and was used as a tool to encourage and strengthen marginalised African American communities in 1930s America. The 1970s in America also saw the surge of street dance as a form of expression too.

“Lindy Hop as an art form is inherently anti-racist”, shares Angela. “It came out of struggle and segregation. Lindy Hop cultivates space to move freely and express yourself in such a way that it combats these unhelpful stigmas and prejudices.”

Angela mentions her process of being curious about those around her as a way to find common ground where we can communicate – to speak and be heard. Her interest in the differences between us is what I believe will also encourage anti-racist environments. This curiosity cultivates not only space for individual narratives and histories to be heard but also to remove any perceived barriers between people. This curiosity is weaved into Angela’s practice as a Lindy Hop dancer; through her keen interest in travelling to the USA to engage more in the sociopolitical history of America that has informed the art form’s roots.

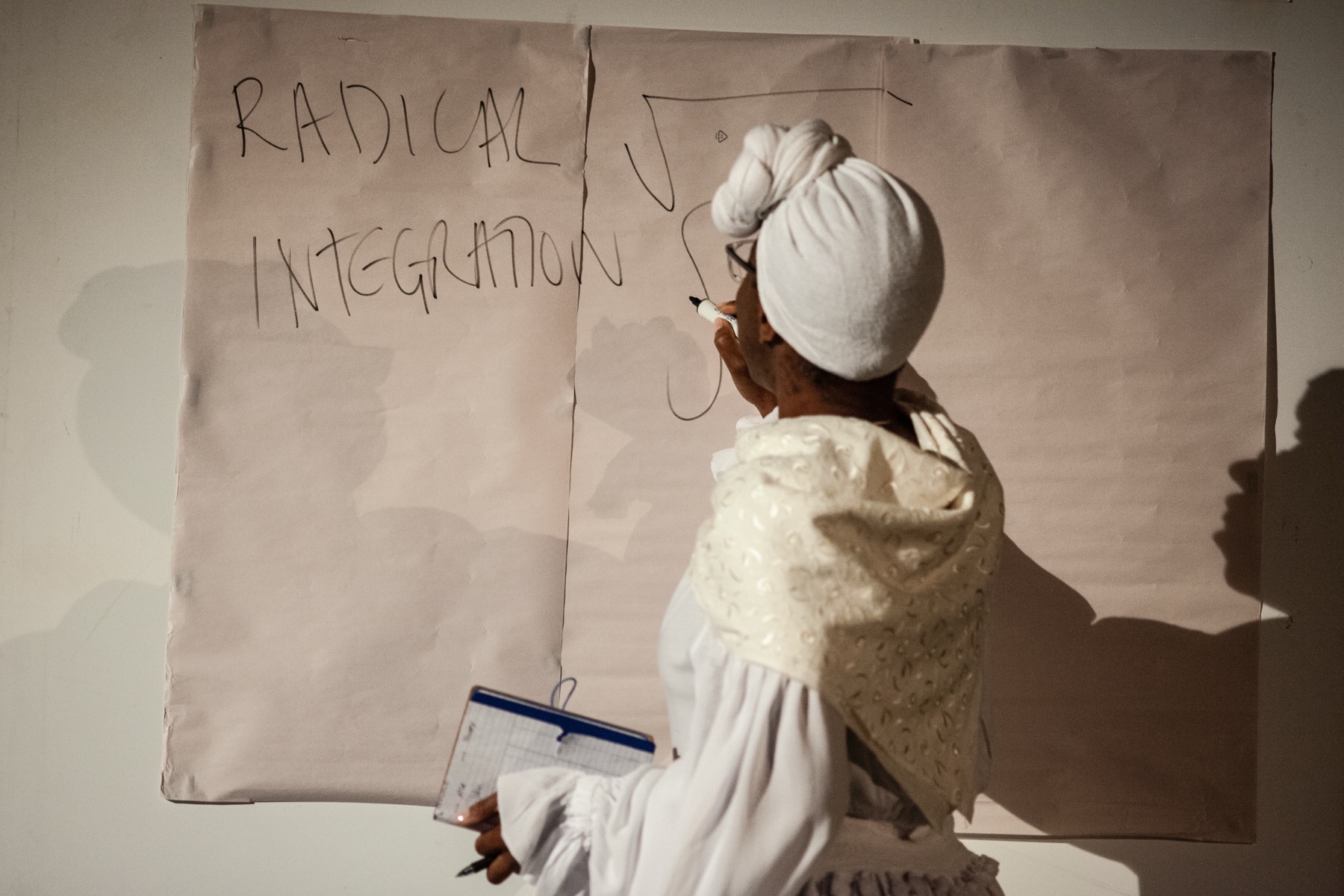

According to Jose, we should be honouring somatic practices as viewpoints of practices that are ongoing and cumulative as modes for anti-racism and decolonialism. Jose offers the value of drawing from our resources of embodied practices to cultivate supported, aware and transparent spaces to engage on topics of race, as they highlight:

“We need to be in a space where we are connected with our mind and body in the present moment, where we are able to practice mindfulness to step out of the space where we are activated by our fears and stresses, and acknowledge uncomfortable feelings as they arise. If we are having conversations about race, mindfulness prior to this may help us have conversations that are open, from the heart and respectful rather than coming from a place of fear or shame. These are real barriers to making progress as a community that wants to make progress.”

As a result of the rich pool of dance artists in the UK, organisations have a valuable resource available to them as examples of practices that may support and contain anti-racist interventions that are integrated into the culture and fabric of groups of people whom anti-racist work impacts most directly. Organisations must acknowledge that the wisdom of how to truly be anti-racist and hold space for this transformation is readily available within the communities it affects most.

Organisations | Leadership

But, are organisations really giving BIPOC artists space to fully lead? Or are they offering inconsequential opportunities that may be sporadic, lacking the infrastructure for empowerment, real systematic and sustainable change?

Taking the lead from artists requires organisations to have a sincere interest and awareness of the issues BIPOC artists face. It also means that organisations should undertake a conscious and active investigation of the complex and nuanced identity experiences and how different marginalities experience racism differently.

“Tiptoeing around naming who we are speaking about is not enough” says Cherilyn, emphasising that it is important for organisations to note and be clear about which part of the artist population they are addressing when it comes to discrimination and issues around racism.

Cherilyn continues to say: “To be an anti-racist organisation, you have to be prepared to hire more diverse people and not for the sake of diversity, for the sake that you are missing out on a lot of talent and a perspective, a way of working with different cultures that can benefit the community you are trying to serve”. Honoring that true commitment means taking real actions and knowing when to take a back seat and make space for others to lead.

Jose mentions their experience with Chisenhale Dance Space as an artist-led organisation. CDS’s model for collective leadership has the potential to sincerely highlight the voices of marginalized artists in direct ways.

Alongside this active facilitation of space for artists to lead, my conversations with Angela, Cherilyn and Jose often came back to how organisations have the responsibility to safeguard racialised artists. This may manifest as articulating incongruences and supporting artists in calling things out and finding solutions to present injustices, while holding an awareness that the answers will not be the same in every circumstance.

Whilst actively working to eradicate racism, Jose shared that people in various proximity to it may have different needs ranging from education, care, an ally, or just space to be heard and seen. Cherilyn shares her experiences of inherent care and nourishment, specifically in a community with black women, regardless of coming from different backgrounds and having different interests. It is my hope that arts organisations will be proactive in providing space, infrastructure and resources for racialised artists to be with their own communities within the supportive structure of an institution.

Legacy

I wonder about younger generations perceiving themselves as BIPOC in majority white arts spaces and how they may choose to navigate this.

Angela touched on a significant story of her childhood in the 1970s where her white progressive socialist teacher would affirm her to become aware of her own identity, to see herself. “She made me hyper-focused on my own identity and that’s why I love teaching because you have the ability to help people be themselves,” says Angela. Angela’s reflections echo memories shared by Cherilyn about the system of self care instilled by the black women around her when she was growing up.

Essentially, practices of anti-racism and an awareness of how we exist in relation to difference within our society is a concept that should be engaged with from an early age. Arts organisations should cultivate spaces for young people to be curious and conscious about race, and facilitate conversations about socio political topics. As we continue to do this work, my hope is that organisations will take both an active and conscious role that is flexible, honours change where it is needed and centres listening. Personally I want to see more work from organisations that also acknowledges, sees and celebrates the strength in diverse identities as there is certainly no scarcity of talent, capacity or desire.