Words by Maria Elena Ricci.

Last Saturday, I sat down for an online conversation with Nigerian-Irish choreographer Mufutau Yusuf. With a smiley look Mufutau told me he had just landed in Brussels, where he is based as a freelance choreographer, and where he was going to rest for a few days before travelling again, this time to London, for the staging of his newest work, Impasse, at Sadler’s Wells Lilian Baylis Studio on November 14th and 15th.

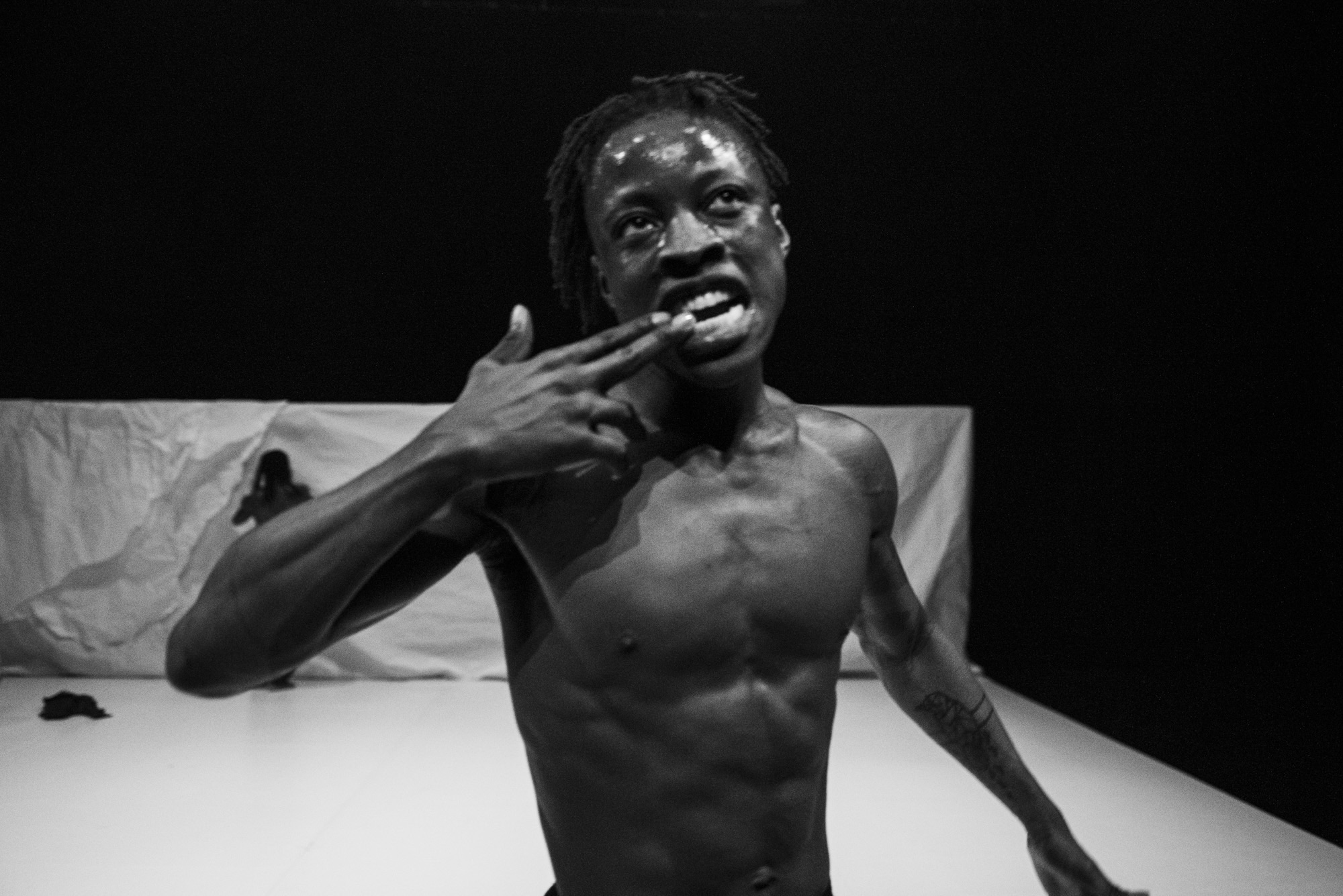

Recently performed in Lyon (France), Lagos, Mufutau’s hometown in Nigeria, and at Belfast International Arts Festival last week, Mufutau’s duet with dancer Lukah Katangila comes to one of the city’s most important venues with an exploration of what it means to be part of a diaspora in contemporary society, personal memories, ancestry and identity.

DAJ: Mufutau, I would like to start our conversation thinking about the role of memory in forging identity. As someone who has traveled and seen different realities as you have, how do you think your memories come into your identity as a choreographer?

Mufutau Yusuf: I think memory is really the common, underlying thread between Impasse and the two solo works I created before. Even without me directly choosing to deal with it, memory manifested itself as a theme throughout my artistic processes.

With Impasse, memory became a tool to shape my identity as somebody of the diaspora navigating a space like Ireland which I wasn’t born into, but I had to I grow up in. I asked myself: What tools do I have to navigate that space? I have my memory, my ancestral memory.

Also as a choreographer, when I get into the studio, I often have images and ideas in my head. Even if I’m not sure where the imagery comes from, I also know it is subconsciously connected to a memory of something that I’ve experienced.

I work a lot with embodied memory. I often try to go from a very experiential place, that is a sensation, an emotion or something that I feel in my being, pour it out physically, and then start to give it shape and form. But that initial sensation relies on a physical embodied memory, and that’s one relating to the choreography.

DAJ: Do you feel like accessing that embodied memory in your creative process has ever been somehow challenging? How do you do it?

Mufutau Yusuf: I don’t find it challenging to tap into that space, but it really requires a great deal of trust and opening. Through my college days and for a few years after, I was trying to locate myself in different kinds of spiritual practices, from Buddhism to Hinduism, to find a way to connect deeper to myself. Over the past year, I’ve just been going back to my own indigenous identity within my Yoruba culture.

One element that truly moves and interests me about my culture is the connection to the ancestral world. Some may see ancestry as abstraction, but it’s actually something very real. It’s about trusting yourself and opening yourself up to that connection. If you can do that, you can tap into a memory pool. For me, the challenging part is not accessing memory, but making that intangible image tangible through my dancing body and into something coherent.

I do believe everyone has the capacity to tap into their unique personal memories. It’s up to each person to find their own medium or conduit to get there.

DAJ: What kind of memories have brought you to want to create Impasse?

Mufutau Yusuf: With Òwe, my previous solo work, I was looking into my own archive and past. Now I really wanted to explore my present experience as a Black individual in a Western society; as somebody who’s part of the diaspora. I was trying to understand how I exist in this space. What agency do I have? What is my identity? What is blackness in that space?

Amongst everything, I had to look back into my own life, moving to Ireland. Mine was the first Black family in our little town, I was the first Black person in my dance school and in my normal school. In many situations, I was the minority and I learned lots of different ways of coping and navigating that.

My solo partner is from Congo but lives in Belgium, so I was also curious about his experience. Starting from personal experiences, we worked with various images and themes such as migration, identity politics, racial politics. Also, I love working through improvisation, as I find my memories pour out of me and allow me to engage with them in the present moment.

DAJ: Something that stuck me from the performance trailer is the following statement: “Our true aim and desire is to collectively create a space free of oppression, apartheid, colonialism, racism, homophobia and transphobia”. Is it truly possible to create a performance space that is free of oppression?

Mufutau Yusuf: I mean… it’s my dream, I suppose. With that sentence I think I wanted the audience to know that this body of mine is an extension of a lot of other bodies and a lot of other experiences.

As an artist, I feel a certain responsibility to communicate that. I think that, generally speaking, we have gone beyond the attempt of creating free spaces. We idealise them instead of making them happen. How can we then, as a society, stop idealising freedom and really just actualise it? It can be the smallest gesture, like planting seeds in people’s mind and in our social interactions.

Audiences don’t have to politicise or intellectualise what they see, but hopefully start a discourse. In Belfast last week, there was a post-show talk and while I was coming off stage, I heard two women talking about what they got out of the piece. It really warmed my heart and that conversation, hopefully, will translate into action, generating new ideas, conversations and input between more people.

DAJ: Can you can talk about the Yoruba costume used in the piece?

Mufutau Yusuf: That specific costume is inspired by a Yoruba masquerade costume called Egungun. You’ll see it in different colours and models in festivals around Nigeria. It symbolises the ancestors coming to the world of the living to deliver messages, warnings and to simply interact with people and guide them. I wanted an element of ancestral entity to exist in the performance space, also to represent my own ancestral lineage whilst respecting my culture.

That is one idea behind the costume, the other is the laundry bag, the coloured striped bag you’ll often see in West Africa, Latin America or India, which people use to travel and often times to migrate. Some people don’t have suitcases, so they might use this bag as it’s very resistant. For me, it represents migration.

I wanted to see how I could have that element mixed with the masquerade, so I imagined if I could have a god of migration, a representation of the ancestor as a migrating being. I was working with an incredible costume designer, Alison Brown, who was very open to the idea. We did a lot of research together and had many discussions before she actually started developing it.

DAJ: Mufutau, what happens to the body, your body, and Lukah’s body in the performance? What is the sentiment you leave on stage once you finish performing?

Mufutau Yusuf: To put it very simply, there’s a sense of transcendence. I feel like we transcend the body at some point. It evokes the ritualistic experiences in West African rituals, where you go through very intense physical experiences to transcend and go into that outer realm of existence.

To some degree, myself and Lukah do experience that because it is quite a physical piece. In the beginning, it’s a bit slow, but then there’s a section where we are really pushing our bodies’ endurance through repetition, like a cycle. We also run a lot!

We begin with a very disjointed figure, a break away from the stereotype, and then a journey begins. Along that way, we meet and find a sort of unity. We harmonise and reach a place together.

To find out more about Impasse and Mufutau visit here.