Words by Francesca Matthys

Malik Nashad Sharpe, aka Marikiscrycrycry, and I sat down a couple of weeks ago over Zoom to talk about their practice and new work Goner a horror dance tale to tour across the UK and internationally from 2024-2025.

I had seen a process sharing of the work in 2022 as part of Fest en Fest so this felt like a full circle moment.

You may have heard or seen this intriguing alias around and I personally was initially quite excited to finally ask them what the inspiration behind ‘Marikiscrycrycry’ as a performance name was.

“I started using this alias in 2014. It started out as me trying to find a container…to make work with a similar set of questions. When I was younger I felt very galvanised by the political situation around me. It was the emergence of this spectacle black death and the fallout of Obama (I grew up in the United States) so I wanted to create a space where I could ask questions about what it meant to be a marginalised human being and not feel afraid that I would be punished by the potentially political things that would come up in the work that I would make. It has evolved so much since then. I wanted to connect an emotional experience of marginalisation and the anger and desire for an alternative view on black life.”

Malik’s lineage finds its roots in Trinidad and St Vincent & Grenadines as well as a history of migration through many generations in their family. This alongside their complex American identity informs their work.

“For Goner, it was the first time I was going to really look at my Caribbean heritage in the form of the movement material and sounds. I was also like, is there a Caribbean tradition of horror? I found it interesting to pair Goner, island culture and singularity. I thought, let me work with what I think my cultural heritage is.”

I relate with this very much as it is a common experience of younger generations that come from migrant parents or disrupted cultural identities, to search for their own reimaginings of culture from what has been passed down, gathered over time but also what genuinely feels significant at a particular time.

Goner shows this in its references to Caribbean movement language and the freeing of hips. From its first few moments, Goner directly references contemporary Caribbean dance styles such as ‘Daggering’ and ‘Whining’, deconstructed and juxtaposed with contemporary pop culture such as music and cinematic aesthetics.

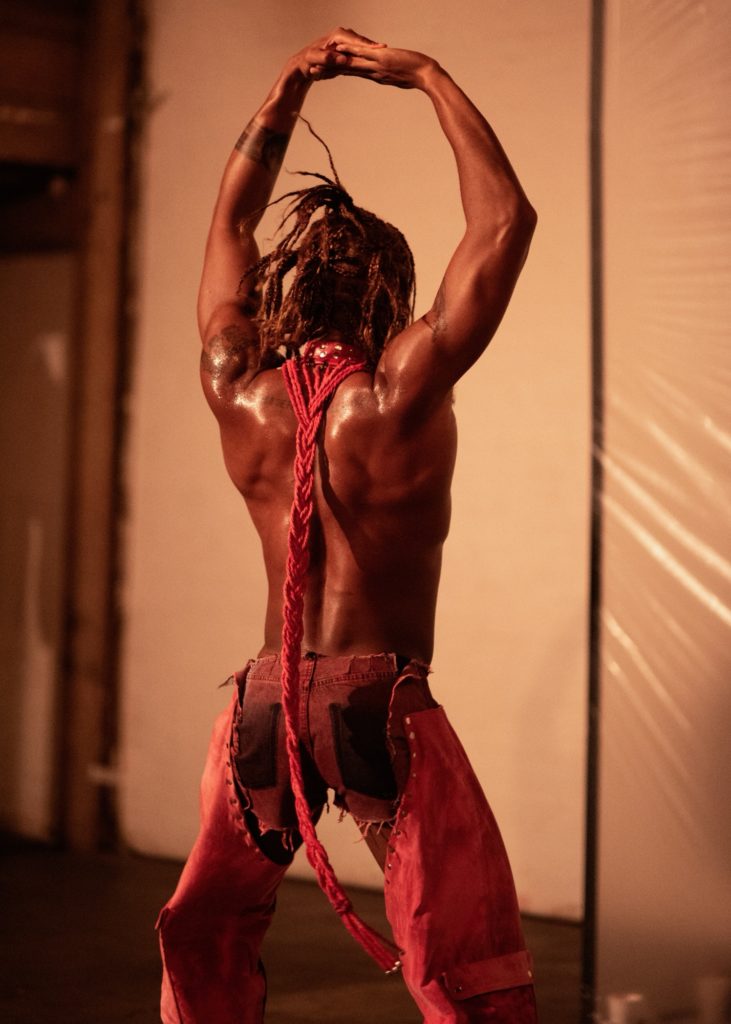

In Goner I was hypnotised by the organic and intentional hip movements that were sustained and almost durational. Sweat dripping from their body, their back was the only body part exposed to us for a while at the beginning of the work. This reminded me of cultural norms present in African cultures such as not looking at elders in the eye as a sign of respect.

Through Goner’s first moments, it felt both intimate to the self and very much a spectacle. There is liberation through the central part of our bodies where we store trauma and the harnessing of personal power. I was captivated by this and the contagious music that echoed through the ICA performance space.

I had mentioned to Malik from seeing Goner’s previous iteration in 2022 that I could watch this beginning section on loop, forever. And it was true. I think our attention span as audience members is potentially decreasing due to fast paced algorithms and the abundance of viewing options available to us on our screens. I appreciate the subtleties of this movement and the commitment to exhausting an idea.

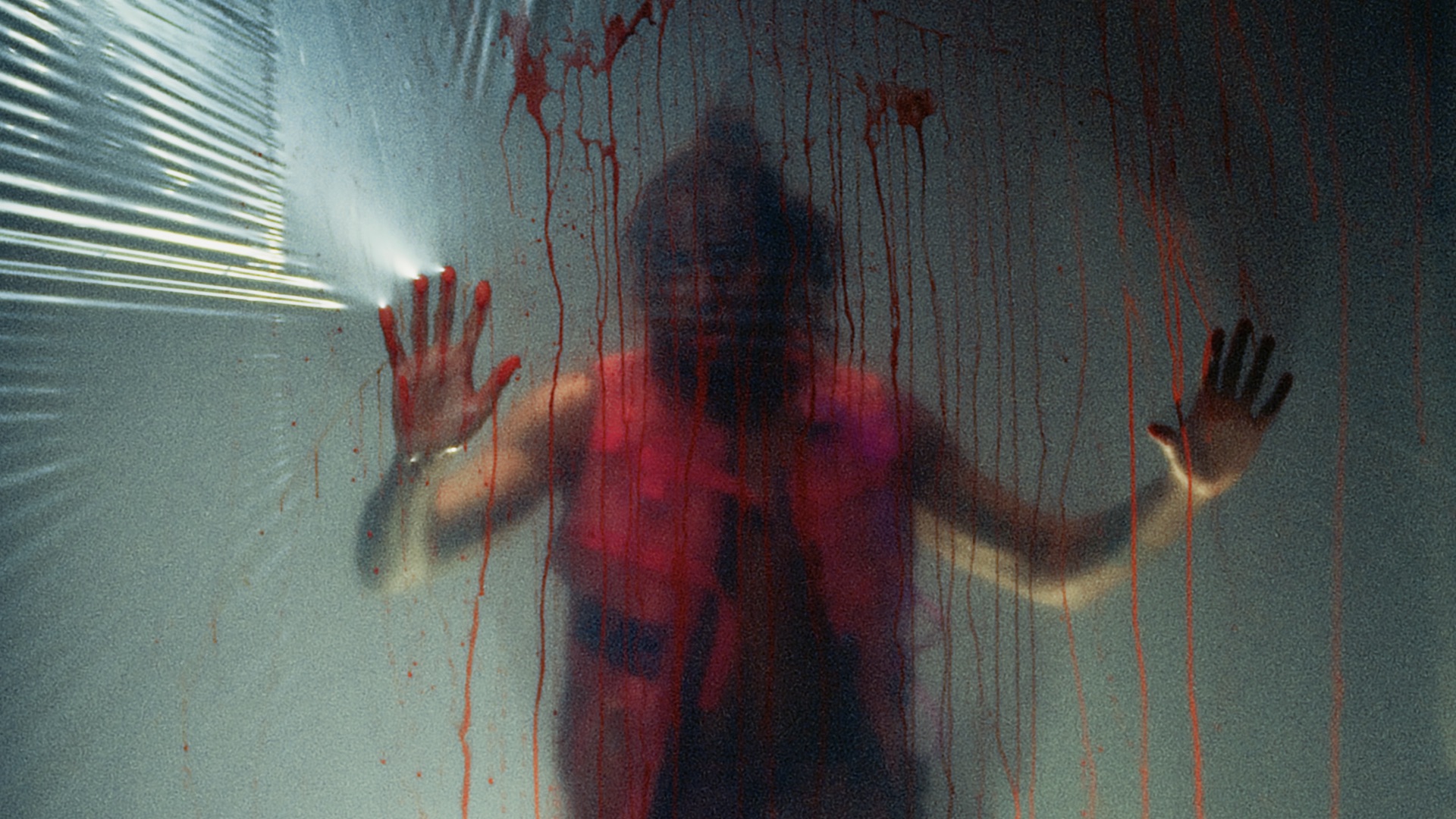

Glued to this movement, I had completely forgotten that the work existed within the genre of dance horror until an unexpected reveal that I will leave for future audiences to find out.

Goner is Marikiscrycrycry’s first solo in 10 years. During our interview, they share that the process of creating Goner was a reflection on what had risen in their practice after all this time. Horror was one of these discoveries and ties in with a common thread through their work: A direct and clear expression of existing in a marginalised body.

In this iteration of Goner, narrative became important as a tool to connect further with the genre of horror, as offered by musical director Tabitha Thorlu-Bangura. The use of text through monologue and song are strong anchors that enable us to journey through a tangible and relatable story. It may at times feel as if we are in a frightening purgatory where the protagonist must endure pain, anguish and humiliation but the storytelling connects us to their sense of humanness in the real world with its socio-political context.

Aesthetically there is a strong thread of horror dramaturgy through the many layers of red. Red suede/leather on Malik’s body and red rope around their neck. Both elements that can be viewed through lenses of kink as well as the oppression of past and present peoples. These blurred lines between sexuality and fear are present through this performance in ways that really affect us as audience members. We are privy to an empowerment of the self but also a vulnerability that is very revealing.

The theme of red is always present with us through the garments and props. Red is a colour that represents the gory side of horror that we know but also the very present reality of bloodshed of black queer bodies. The leather chaps, historically worn by cowboys, is perhaps coincidently or perhaps intentionally parallel to the release of Beyoncé’s ‘Cowboy Carter’ that may be a reflection on the lived experiences of black bodies being isolated from certain historical cultural spaces such as the country music genre.

My eyes were also drawn to the performer’s shoes, running trainers to be exact, which allude to a very athletic state but also the readiness to run away from something or someone at any point. This is echoed as the performer is subject to an external voice that can be easily perceived as that of the American police. There are many moments of violence through the work, dramaturgically expressed in ways that are very intelligent and poignant.

Solo work is often perceived as a very solitary process and sometimes this may be. However, Malik said that Goner was hugely collaborative , and we shared sentiments that I hold dearly such as allowing collaborative artists to sit in their expertise and trust that it is their project too. “Goner wouldn’t be what it is today without their hard work and dedication…It makes a far more rich experience when people can do their practices with you.” This democratic approach to making is an extension of this world that Marikiscrycrycry shares with us as witnesses.

As a dance artist who works in conversation with other disciplines in dance making, I appreciate the interdisciplinary nature of the work that is an earnest product of trusting all these collaborations and also the flexible and non-limiting approach that Malik holds. They chuckle as they share that this cross discipline process is foundational to their practice…

“When I first started I was programmed by no dance venues. It took a while to get through the dance door because people were like, is this dance? Interesting, why don’t you think this is dance? Because I speak? You don’t think dancers should speak? It’s changed now but when I first started…”

Yes, yes, and yes again! Why are we limiting dance and dance makers – why are we being confined when our creativity is essentially limitless?

This conversation with Malik and seeing their work was so inspiring, so moving in both the way that they view the world through their practice, and the exciting and unexpected work that they produce. Who would have thought that dance, horror, culture and crimson cowboy chaps could come together in such a nuanced offering?

This excites me very much. We love to see it!

For more information on the Goner tour visit here.