Words by Rodney Murray.

I’m not a guest-list person. Despite any personal or work related affairs, my name is not usually relegated to that document reserved for an elite few. In the same way that I’m not a guest-list person, I’m generally not a “dance in a museum” kind of person either. Simply, I hardly find myself in proximity to either of the two, and sustain the belief that both are superfluous and entirely too bourgeois. Such belief, however, was sustained only until Saturday the 22nd of January, wherein I found myself in intense proximity to both a guest list and museum dance. In short, I was on a guest list, to witness a dance in a museum.

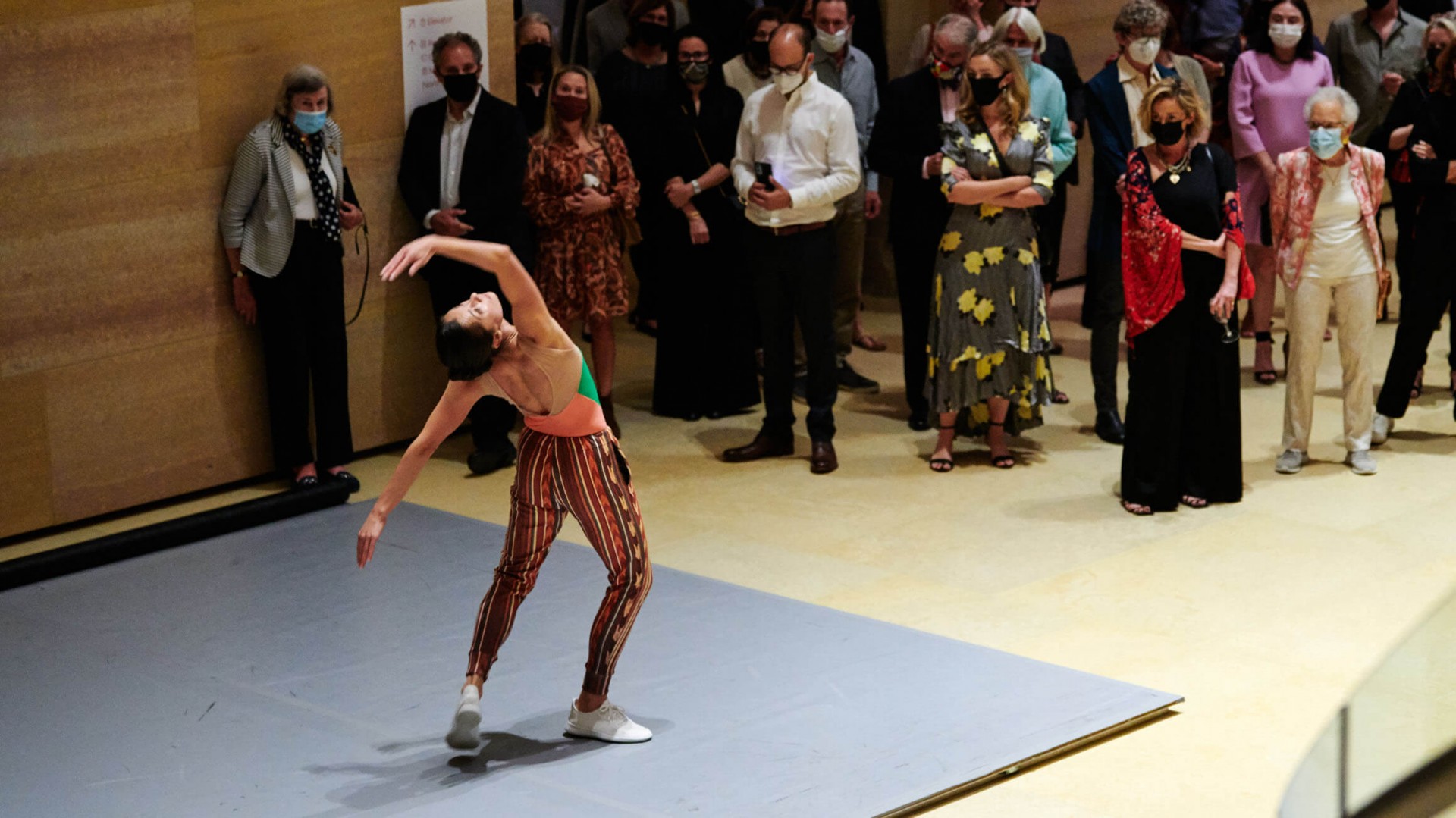

The museum in question is the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the guest list in question was one such for Finally Unfinished (Solo for Melissa for Jasper), a new, 20-minute work choreographed by Pam Tanowitz and performed by Melissa Toogood in concurrence with the Mind/Mirror exhibition. Dually curated at New York City’s Whitney Museum of American Art by Scott Rothkopf and the Philadelphia Museum of Art by Carlos Basualdo, the monumental retrospective exhibits Johns’s iconic works from as early as 1954, including his enigmatic Flag. Toogood, whom I spoke with earlier in the week, is the Rehearsal Director for Pam Tanowitz Dance and has a history as a dancer with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company; starting in 2007 she danced through the Legacy Tour which continued into 2011.

I was running behind on this particular morning, so I opted out of my typical bus route and called an expensive Uber instead. Pulling up to the famed Rocky Steps and Stute, I was of course unsurprised to see both flooded respectively with millennials participating in group workouts and families capturing posed pictures for Facebook memories. Entering the newly renovated museum space, I walked into Lenfest Hall, and peered down my nose past the large staircase, where I was almost giddy at the sight of two marley floors – one classically large, the other, maybe 10” x 10”.

Confirming with a crew member that the performance was set for this space, the crew member hinted that the best seats are in fact above, peering into the square-like well of the Williams Forum, and that Toogood would be travelling from above, down the staircase, and onto the marley. Taking her advice, I situated myself on a cushioned bench, just shy of a glassed-in guard, and observed the guests in seemingly endless streams, coming and going, most of them unaware of the fact that in only five, short minutes, they would discover themselves in the middle of an exquisite happening.

Like a sparkler whose necessary remnants burn your arm, her movement is caught in similar fragments and their images burn into my eye. A leg outstretched and a head released, arms in a warrior-like pose, I take whatever I can hold onto. Soon, she is moving down the stairs, and arriving upon the landing, pendulums between audience members who can’t decide if they are in the way. I can’t either.

After a few moments, a woman with an expeditious yet pedestrian gait rounded the couch and stood in front of me.

Albert Yee, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021.

Dressed in a neutral-colour, tribal-like patterned sweatsuit, she gestured to the crew member who I had spoken with minutes earlier, and with the surprise beginning of music composed by Caroline Shaw, Toogood commences on a kind of explosively calculated allegro series in tandem with sonic staccatos, where only seconds after, she turns to me with her passé held like bated breath, and unleashes a corporeal geometry with her arms and legs, all the while keeping her eyes fixed on mine.

Here, a dance for the dancer, a selfless gift, which, wrapped underneath the incisive and definitive gestures of her arms and legs, is a kind of timeless lineage and sanctimonious appreciation for the work that we share. I’m too thrilled, scared, and uncomfortable to maintain eye contact but I’m too excited to break away, so I do both. I recall what she said to me in our earlier conversation, that she “[likes] being that close to the audience”, and that “there’s a lot of dancers, that wall between them and the audience is protective, and for me, that’s the place where I don’t want to be.” There is no wall.

Instead the space between is a raw nerve that we both keep teasing. Before I catch her eyes again, she’s going, going, gone behind a pillar. I think to follow, maintain the dance between the two of us, but I stay, now standing, and decide to let her reveal herself to me.

I catch flickers of an arm or a leg as she moves through the audience (those who know and those who don’t) and ultimately closer to the staircase.

Like a sparkler whose necessary remnants burn your arm, her movement is caught in similar fragments and their images burn into my eye. A leg outstretched and a head released, arms in a warrior-like pose, I take whatever I can hold onto. Soon, she is moving down the stairs, and arriving upon the landing, pendulums between audience members who can’t decide if they are in the way. I can’t either.

Arriving at the marley, Toogood takes off her shirt, revealing her melon-toned leotard designed by Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung. She lays down, scrunches the shirt into a pillow, and gazes upward. Looking down, I can’t help but revel in the cinema of it all. The dimensionality of the world, the dimensionality of the space. Toogood watching us watching her. Moving to the last plot of marley she removes the last of the sweatsuit, and ornaments herself with a sheet of pink tulle. Suddenly, the athleticism of her movement, the youthful sprightliness in her allegro, she is consuming the space in the way only a Cunningham dancer could. Watching Toogood cut images out of thin air and create monumental architectures, I can’t help but refer to the Greeks, their sculpture, their art, their eye for modernity. I wonder if it is all cyclical, or if changes in our relationship to artistic production are incidentally incremental while the root of it all is withstanding. I wonder if it’s all too self-serving, performance, and more specifically, museum performance, but in a moment, I no longer care for the answer.

Reclined on her right arm, with a leg pointed directly toward the sky, Toogood finishes and remains before getting up, walking away, and returning masked to take a bow. Clapping, like the good guest I am, I begin searching tirelessly, like the dancer I am, for a metaphor to make it all make sense, to make the dance coalesce. I pass through thoughts too cheap, attempt to determine what Toogood’s relationship is to the viewer, and ultimately settle on nothing of value. Perhaps, however, that is the exact magic of Tanowtiz’s work and Toogood’s movement. It cannot be captured, it refuses consumption, it evades a container. Finally Unfinished (Solo for Melissa for Jasper) occurs in the museum, adjacent and in relation to Johns’s work, not to open up the space between the perpetually visual and the embodied, but to instead narrow the space enough so that the conceit is clear. Finally Unfinished teases the incompleteness of the visual, for John’s canvases, despite how we may theorize, do not move. Tanowitz creates a work where repetition, rather than reifying meanings, resists consumption, resists becoming an artifact, resists only being seen. The work intrigues the seriality of John’s numbers, flags, and readymades, for in their tangibility, they are always ready to be revisited.

I permabulated through the museum for another hour before leaving. Mostly getting lost or running into a few familiar faces, I boasted about Toogood’s performance and Tanowitz’s choreography. I took in some of what Mind/Mirror had to offer, basking in the magnitude and layering of Johns’s work, but I mostly let it wash over me. Like everything from that morning: the Uber, the guest list, the dance, the faces, they were just the layers of another day.

Header image: Tim Tiebout.