Words by Stella Rousham.

‘The inspiration is my life, I guess. A combination of wanting to fight for dancers, wanting to fight for artists and wanting people to understand how racism works.’

Since graduating with a BA Hons from London Contemporary Dance School, Valerie Ebuwa has performed with renowned companies such as Vincent Dance Theatre and Clod Ensemble, modelled, mentored, written for I am Hip-Hop Magazine and taught yoga.

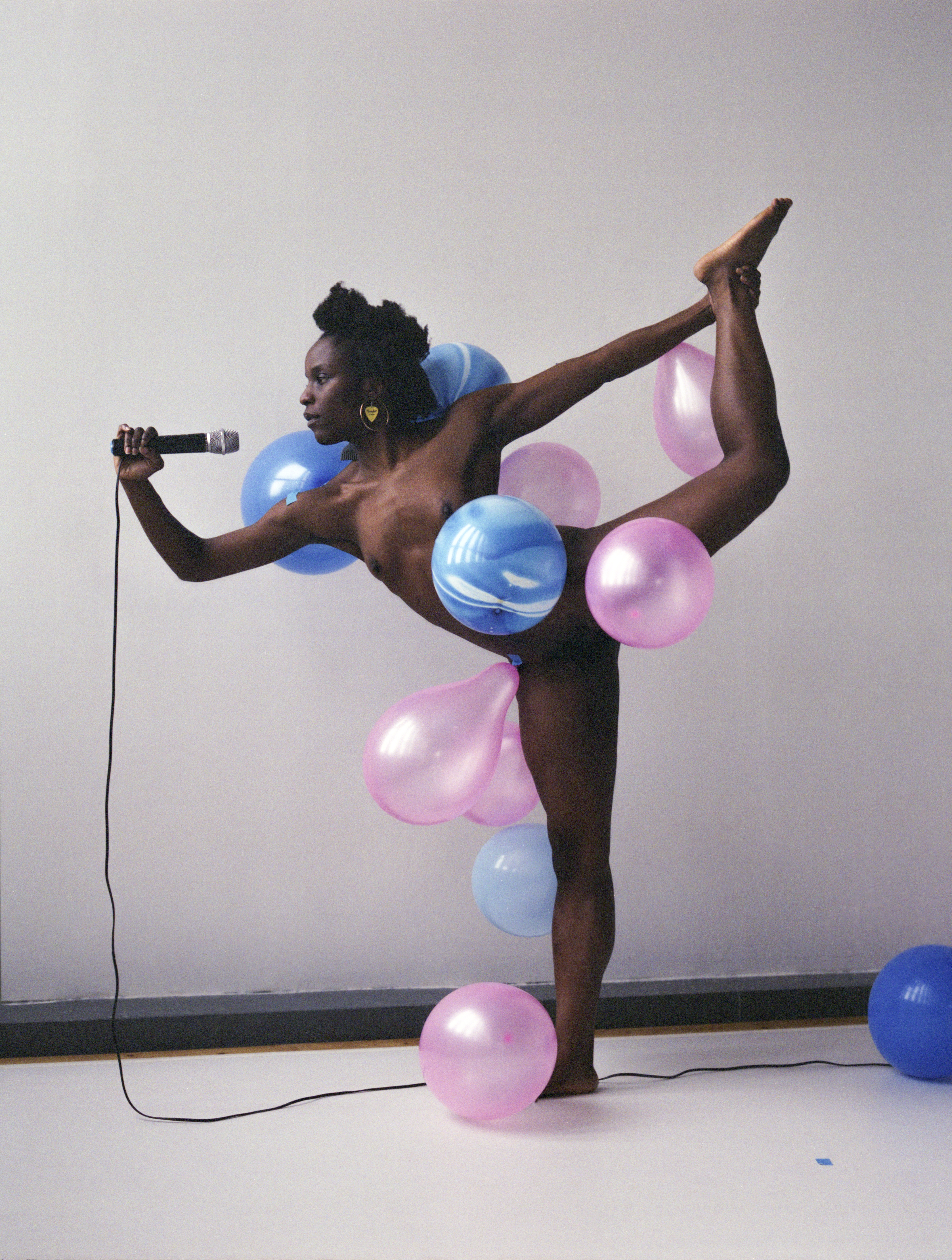

Valerie’s latest work Body Data takes the medium of screen-dance to provide a fresh perspective on the naked, black, female form. Whilst COVID-19 may have prevented Valerie from performing and delivering a talk on Body Data at the V&A as initially planned, she is nevertheless determined to honour and value her art, continuing to publicise and release material on various social media platforms.

S: Thank you for taking the time to speak with us, Valerie! What’s the inspiration behind Body Data?

V: There are so many inspirations! I feel like every time I do an interview it changes how I see and view it. I guess the initial motivation was the fact my dance career had really taken off. But although I was becoming more and more successful, it still wasn’t consistent enough for me to be able to make a real profit. I started to do life modelling, yet it wasn’t paying well and was pretty inconsistent. It made me really realise that the value we place on bodies is really low. And I wanted to figure out why.

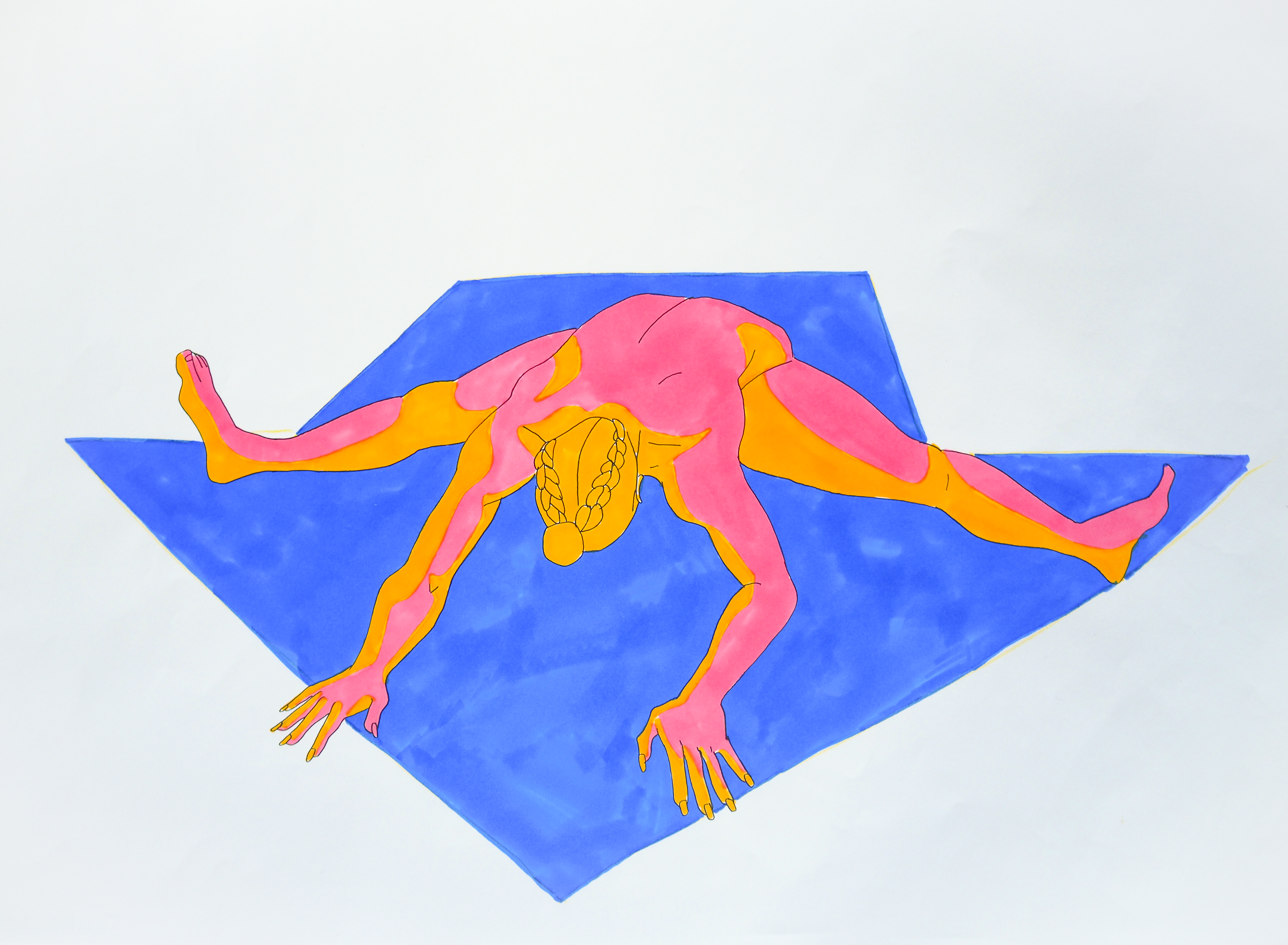

Most people couldn’t draw me or paint me properly, and I can’t work out if it was a lack of skill, or if it was really because they had never drawn a woman that looks like me! Was it because they hadn’t had practice, or because they only see whiteness? Only see themselves? But when people could capture me, I felt like ‘This person sees me!’ So, I guess the inspiration came from wanting to give back to those people; what they gave me during that beautiful exchange.

I guess essentially, the inspiration is my life. A combination of wanting to fight for dancers, wanting to fight for artists and wanting people to understand how racism works.

S: People are so scared of talking about racism.

V: So scared, so scared of saying what it is! We have words for a reason, it’s mind boggling. It makes me laugh — that’s why I find racism so funny. Whiteness has never not been justified, so when I tell you that something is racist and you say no it’s not, why do you have to justify your existence by erasing mine? I have never had an existence that has been justified. Never. Two experiences can co-exist. I can listen to you about your experience of the world, why is it that you have to erase mine? We can be powerful together.

It’s about love and compassion. If we all looked at each other with compassion and love, then you can really see the person. We can have a collaboration that is so fruitful for both of us. Why does it have to be this: ‘I have to shove you down’ or ‘I have to force my power’.

S: A big reason why I myself and many others are deterred from going into dance is because of the precarity of the industry. It makes me so sad because I know that’s what I want to be doing.

V: See this is the thing, and this is why I love it. Life is precarious, you know. Don’t be dissuaded from your dancing because of the precarity of life. Who would’ve thought this would happen now?

You should never ever be too comfortable in anything really, because you never know what’s going to happen. I’d rather live and do what makes my heart bounce and see what happens.

S: You wrote an article on the racial stereotypes in dance reviews: ‘Sometimes you need to review the Reviewer’. Would you like to explain your experience behind this?

V: I got sick and tired of reviewers who were blatantly racist. Blatantly racist, absolutely racist. They wrote “Valerie did this ‘lovely routine”. They’d never write that about Hofesh or Sidi Labi – they’d say the “choreographic phrase”. Don’t you dare say that it’s not racist to use a different language for my body. That keeps bodies that look like mine in a specific category or a specific box that is always in submission. It’s always lower, it’s always of a lesser value.

This is why hip-hop dance doesn’t get any money. We have one hip-hop festival in the UK, and that is Breakin Convention’. I get three days to enjoy hip-hop dance. Three days???

S: What do you think the role and future of dance writing and reviewing is?

V: Because I review dance, I think that it’s interesting to recognise the perspective that a performer or a choreographer has over reviewing dance. You understand the process of what it is to make a piece. You understand it on a physical and mental level.

For me, if I know something then I have to honour it. I have to tell the story in a way that is most honourable. If I don’t like a show then I don’t write the review. I’m very mindful of offering my advice because it’s about taste. That’s what’s so difficult with reviewing, it’s about taste.

I think it’s also about how you’re introduced to it. I was aware I could write about dance because when I was at Laban Youth Dance Company, I got to sit in a session with Judith Mackrell.

S: Do you think that change needs to happen in dance training? When I think of The Place, Laban, Northern, they are based on ballet and contemporary. From the start you’re told this is ‘technique’ and these are the ‘official’ dance styles. Then ‘other’ dance studies like hip-hop will always be framed as ‘secondary’ or ‘alternative’.

V: Yeah, a hundred percent. What we know as technique, is super colonial. I’m not saying these colonial techniques need to be removed from the syllabus because I think they do have some value and importance.

But there needs to be a change in the delivery of these techniques and the balance of ‘other’. If we all group these techniques as ‘techniques’ and just did them on an equal basis, then it would help to dissolve these ideals.

Then again, it’s also a question of who is teaching it. If I had a black ballet teacher I would be a ballerina, I’m telling you this now. I felt like I couldn’t be a ballerina because so many people told me I couldn’t. People come up to me and when I tell them I’m a dancer they ask if I do hip-hop. Nope, can’t be anything else. Maybe if I was white you would say ballerina first?

I think the impact of seeing someone different — even if it is within a colonial technique — will start to undo the many reasons as to why this current system is failing. People need to have a black woman leading a class. It just has to happen.

And it’s tiring for me, it’s tiring. But I also understand my responsibility. I know I have the knowledge, heart, passion and compassion to do it.

S: How have you been dancing and moving in quarantine? How have you adapted to this life?

V: I had my first proper dance class today, as in a rehearsal. I dance for a company called Clod Ensemble and it would’ve been the premiere of a show we were going to do called Black Saint and Sinner Lady. At this stage it feels like I’ve been thrown into a computer family, with people that I’ve never danced with, people I haven’t physically touched.

Now that the V&A is postponed, it’s allowed me to see the project [Body Data] in a slightly different way. Can I actually finish it in isolation? Will it have just a digital presence which I can gift to other people? Do I include more bodies, do I replicate myself on screen, do I get more funding? What have I not touched on? Colourism. Should I do more talks? Should I do it as a lecture? I think this COVID situation has brought a lot of excitement and possibility.

Keen to watch, listen and find out more? Watch the full ‘Body Data’ film on Vimeo at https://vimeo.com/319312029

Check out Valerie’s work further on:

Instagram: @valerie_ebuwa

Facebook: Valerie Ebuwa

Website: https://www.valerieebuwa.com/about

Header image: Henry Gorse.