Words by Ines Carvalho.

On International Women’s Day, we pay tribute to the greatest choreographers who translated feminism into movement. As modern dance started to emerge, the stage has become a space for new ideas and concerns, holding up a mirror to society and its contexts. Dance has been questioning and breaking down barriers and perceptions of the female body; once traditionally seen as the fragile, immaculate ballerina. Dancing side by side with the feminist movements, the history of contemporary dance correlates with gender equality and what it means to be a woman beyond stigmas.

Since Elizabeth Cady Stanton uttered her 1848 speech about the need for women to take control of their own lives and roles in society, a collective voice started to be heard. It was the first wave of feminism which advocated not only suffrage rights, but also female reproductive rights and economical independence.

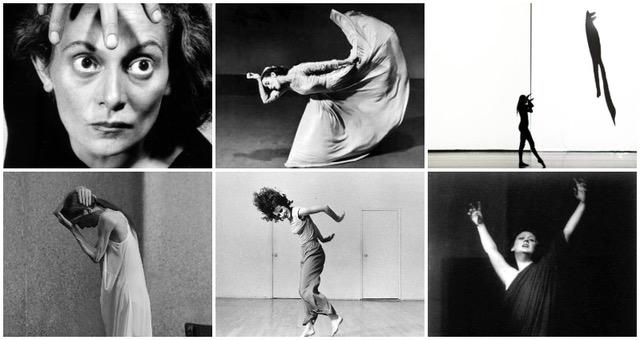

By this time, the European ballet was starting to become popular in America. Considered by many as the mother of modern dance, Isadora Duncan deconstructed the image of the classical ballet dancer by creating ‘free movement’. Inspired by Greek mythology, she arranged her own way to loosen the cultural scenes of her time. Even though she was strongly criticised, her costumes and concepts highlighted a female figure who wanted to break free from the old standards.

Another obligatory name of the first wave of feminism in dance was Martha Graham. Despite never identifying as feminist, her work usually brings women to the centre of the narrative. She agreed the conventional aesthetics of ballet presented an unreal image of the female body. Graham’s repertory is filled with female characters who are experiencing an inner connection to their own nature. They were embracing the energy of contractions; a revolutionary movement which connects the inner self with the physicality of being a woman.

Working in the same period as Martha, Katherine Dunham was an essential champion of black feminism and the African diaspora in times of fierce segregation. Through her dance work and social activism, Katherine conquered racial and gender injustices and brought solidarity to a discrimination-plagued America.

The Germany expressionist choreographer Mary Wigman further emancipated the female body from the binary gender model. She crossed the limits of male/female identity by bringing up into performance a liberated female body who stands out from limited gender representation.

While avant-garde dance artists were developing new styles of movement, the first decades of the 20th Century were also marked by ups and downs. In the 60s, there was concern the ‘sexual revolution’ was not so liberative after all. While a second wave of feminism started to appear, the Judson Memorial Church in New York was opening its doors to a collective of artists who rejected modern dance principles. The Judson Dance Theatre was based on experimentalism and improvisation, which brought together Lucinda Childs, Trisha Brown and Yvonne Rainer. They debated how to display the female body without being a mere visual object for the audience. These three women reimagined performance beyond the bodies — the lack of expression, unisex outfits and the cerebral tasks on stage erased the sensual image of the ‘woman’.

This conceptual vision gained intensity during the next decades. In Europe, Pina Bausch became a bold figure of contemporary dance. The feminism in her work is raw and real; the woman is part of a duality between social models and Pina’s fierce nature. She kept creating in the period of the third wave of feminism from the late 80s. But its stronger icon was the Canadian Marie Chouinard whose work was sometimes not considered as dance, but as ‘body art’ or ‘performance art’.

Ahead of her time, Marie was disinterested in the distinctions between the female body and the masculine. For her, gender was non-binary. Marie was and continues to be obsessed with the body; its tissue, its systems and its mysteries. She is, characteristically, anti the stereotypical assumptions (and imageries) which are projected onto ‘gendered’ bodies.

Facing a fourth wave of feminism — and strongly influenced by the #MeToo movement — dance is now looking at feminism through the lenses of gender fluidity, discrimination and abuse. In such a globalised era dance is more plural than ever. Dance is part of this story, and these inspiring choreographers have changed the world of dance by debating what it is to be and identify as a woman.