Words by Giordana Patumi.

Last night at the BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Dimitris Papaioannou’s The Great Tamer made its New York debut. The piece, produced by the Onassis Cultural Centre of Athens, premiered in May 2017, and since then has been performed all over the world.

With its ten performers (Pavlina Andriopoulou, Costas Chrysafidis, Ektoras Liatsos, Ioannis Michos, Evangelia Randou, Kalliopi Simou, Drossos Skotis, Christos Strinopoulos, Yorgos Tsiantoulas, and Alex Vangelis), seven men and three women, The Great Tamer depicts the relationship between the afterlife/ Hades and the mortal world, offering a kind of cosmogony on the very essence of the concept of time and its “vanity”.

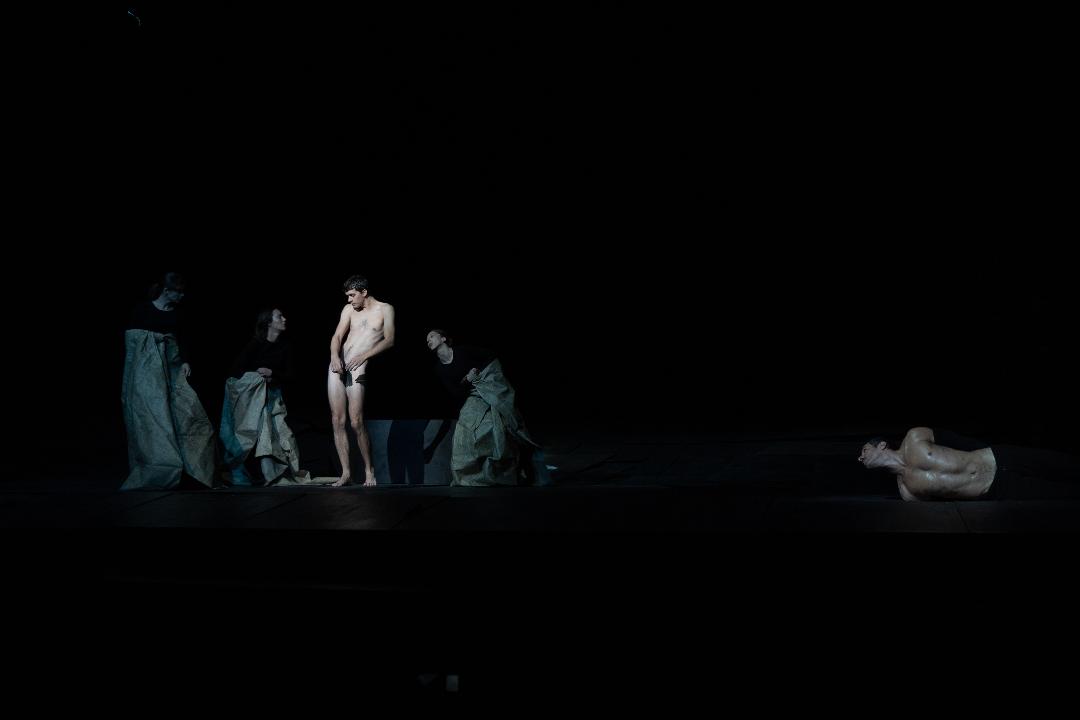

From the beginning The Great Tamer seems to be a careful study of the body, where pieces of human limbs move easily, regardless of whether they are connected or not to each other. Bodies are also mixed to form strange beings with three torsos and three heads, which walk in an awkward and carefree way.

The show takes place on an empty, bare stage, composed of large axes, detached from each other. During the show they will be raised, overlapped, torn like large panels or walls, leaving the space for the unknown of the underground. It is from there that the performers will enter and exit, from time to time, in a great, perfect and surprising scenic game. Every picture is perfectly and illusionary, appearing and then vanishing. Everything is presented in a slow and calm way, very minimalist.

The initial image of the black shoes left on the stage, hardly detachable from the floor, is emblematic. As soon as the man who wears them manages to detach them, they reveal roots fixed to the soles. The entire show is constructed around revelations of continuous discoveries and occultations that have their roots underground, in search of the hidden layers of human existence.

The first performer on stage undresses and “dies” naked five times on the ground, covered by a white sheet laid out by a companion but designed to fly away. It is a reiteration, an expedient dear to Pina Bausch, and resumed towards the end, but without further links with the choreographer of the Wuppertal. The impeccable and more than expressive performers often return to that ‘Body Mechanic System’, a method invented, and already copied, by Papaioannou himself, to distort the bodies in illusory physical “butcheries”, and to make them interact in that battlefield that is the stage.

The extraordinary ‘Strauss’ Blue Danube’ waltz, adapted by Stephanos Droussiotis, is the background music for the entire duration, cleverly stretched, slowed down and modulated. But it never takes the audience away from what they are experiencing. From here, the gliding arrival of two astronauts slowly extract from a abrupt lunar hole a young ‘Christ’ dressed if not just from a veil on the pubis.

In another scene, a dancer carries a globe on his shoulders. A young Narcissus basks in the light of his mirror of water. A dancer moves by crawling her frailly thin and naked body across the stage, whilst a dancer tries to dig his belly with his fist. Two naked bodies roll to form a mixture of perfect form and movement. A skeleton rests on an inclined plane and gradually slips away, bone by bone, crumbles.

Nothing is terrible or macabre or absurd. It is beautiful to see, to listen to, to admire. It’s a wild hybrid between sacred and profane. Fertility and sterility, hence, light and darkness, are the other themes that emerge in this fresco without words, silent and obscure in the process of proceeding through paintings, which celebrates that classical civilization whose legacy is, for the Greek artist, inescapable.

Anyone looking for pure dance in Papaioannou’s performance would be disappointed; here we are in front of an iconic image-theatre, with a strong intellectual and imaginative impact. The only few moments in which dance seems to be the protagonist includes the entrance of several globes, small and large, which performers, equipped with stilts and sticks, try to fly through ropes.

There is no dance in the most common sense of the term or even Bausch’s theatre-dance memory, but rather a large, enormous living installation in continuous evolution and movement, in an incessant relationship between the ground and the subsoil: cleverly facilitated by the scenery made of lightweight slate-coloured wooden panels, set up in waves.

Images: Matt Gordon.