Words by Bengi-Sue Sirin.

Birmingham Royal Ballet’s mission statement tells us they intend to “create a legacy of new traditions, new talent and new ballets.” This is mostly achieved by the programming of their Autumn Mixed Bill. The entirely new ballet ‘A Brief Nostalgia’ opens the show, choreographed by 25-year-old Jack Lister on the BRB dancers. Following that, is literary choreographer Cathy Marston’s ‘The Suit’, showcasing the relatively new talent of the UK’s increasingly sought-after eight dancer company, Ballet Black, in a bill-sharing feat that constitutes the start of a new tradition. Finally, a piece by legendary American choreographer Twyla Tharp is revived, the no-nonsense titled ‘Nine Sinatra Songs’ – one which diverges from BRB’s otherwise modern bill.

‘A Brief Nostalgia’ — Jack Lister

In contrast with newness, rising Australian choreographic star Jack Lister chose instead to theme his commissioned BRB piece on its opposite abstract: nostalgia. The 2018 film Nostalgia exposed him to the Portuguese concept of saudade, interpreted by Michael Amoruso as “the presence of absence.” We are told in the programme to expect expressions of longing for the past, for things that may or may not have happened, elusive evocations of phantom-limb style memories.

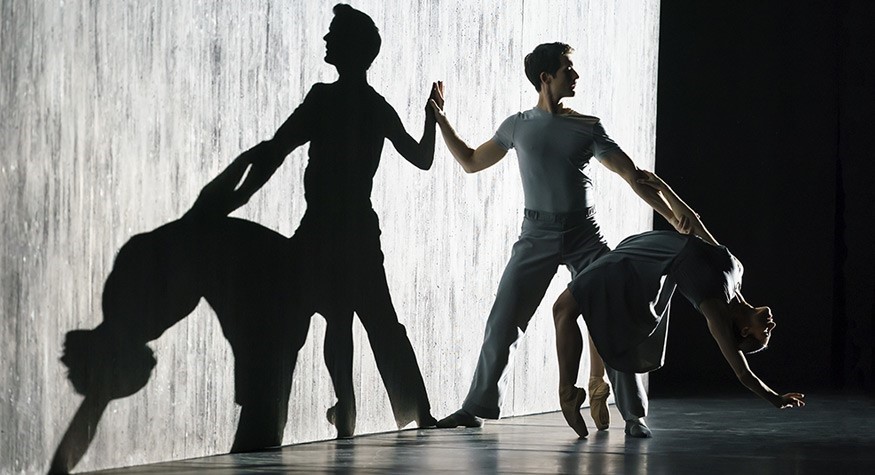

One clear staging of this concept occurs via the use of shadow. Remarkable cooperation between the backstage lighting operators at Sadler’s Wells enlarges the shadow silhouettes so much that they dwarf and almost engulf the dancers making them. I interpret the shadow-selves as a sort of physical manifestation of ‘memory,’ sprouting out of the ‘truth’ of the dancers’ bodies. ‘A Brief Nostalgia’ hinges so much on these dancer/shadow relations, that I write “How did he choreograph in a studio with normal lighting?!”

A slow-motion run, leading into a group lift raising the dancer into the air like the mid-run figure on an athletics trophy, reminds me of the stilted momentum of old stop-motion cinema. The overall greyness of the piece adds to the feel of the past. However, these ‘nostalgias’ cohabit with profoundly dystopian and futuristic aspects. Men lift women in coiled molecular contours, in front of a monolith-like set, which could be perceived as an allusion to either ancient structures like Stonehenge, or the iconic 2001: A Space Odyssey starting point, your choice. A male duet, made up of mirroring, mimicry, and the sense that they are two halves of one unwilling whole, brings to mind Dostoevsky’s The Double, a tale which subjects its protagonist (which one?) to a literal character engulfment like the dancer/shadow relations I mentioned earlier.

And the piece ends on an even more chronologically obtuse note: dust falling from the ceiling, as it would in a very old, decrepit building. Meanwhile two characters, seemingly bound to remain on stage forever, wistfully look out, trapped in an existential, timeless limbo, much like Samuel Beckett’s Didi and Gogo. I certainly encounter the same ‘What did I just watch?’ feeling as induced by Waiting for Godot.

‘The Suit’ — Cathy Marston

We go from ‘A Brief Nostalgia’ to another presence of absence in Cathy Marston’s ‘The Suit.’ An adulteress, whose happy-go-lucky husband Philemon discovers her in the act with another man, is made to carry the empty suit of her escaped lover by way of punishment. Think The Scarlett Letter meets Kafka. It is a cruel, psychologically abusive move by Philemon. In Can Themba’s original story, he tells his wife: “But the point is, Tilly, that you will meticulously look after him. If he vanishes or anything else happens to him…” a shaft of evil shot from his eye… “Matilda, I’ll kill you.”

Sinister, right? Marston certainly projects Themba’s authorial acidity onto the stage. Philemon begins as the image of sweetness and light — seriously, he is, check out this description from the story: “He grinned and yawned simultaneously, offering his wordless Te Deum to whatever gods for the goodness of life.” José Alves endows this happy chappy with a faun-like, ceaselessly smiling skip in his step, relishing the routines of the morning which are comically supported by the other Ballet Black dancers, who offer him his towel, form a human wall of privacy while he urinates…

The delicacy of it all constructs a stark juxtaposition with the post-discovery section of ‘The Suit.’ Tilly’s torment manifests in the corkscrew whirls and anguished kicks of Cira Robinson’s solipsistic solo. As in ‘A Brief Nostalgia,’ we witness descent into a sort of existential purgatory, unable to rid herself of The Suit’.

There is one relief from Tilly’s pain. A social dance scene on the streets grants the Ballet Black ensemble the chance to demonstrate their bodies’ capacities to express joy; an upbeat, low-hipped, turned-out, heel bull change movement particularly stands out. It moves me all the more when I learn that Marston’s choreography here is inspired by the steps of Mthuthzeli November’s parents, who are from the same country (South Africa) and era as Can Themba. Delight radiates! Then, like the crash of the discovery scene, it instantly vanishes. The light-hearted yellow lighting turns moody blue, as Philemon spins his wife slower and slower, like an unhappy wind-up ballerina doll, trapped.

I will say no more on the story, it is worth seeing with fresh eyes. ‘The Suit’ is tremendous: a clear and clever short ballet in the realms of black comedy, made for and danced by a confident and unique company. It deserves all the awards it won, and has carved its place in the woodwork of dance history.

‘Nine Sinatra Songs’ — Twyla Tharp

Onto the Twyla Tharp piece. ‘Nine Sinatra Songs’ is a waltzy, schmaltzy ode to the 1950s. Choreographed in 1982, it has toured theatres and companies with an endurance of popularity comparable to Frank Sinatra himself. The format is un-embellished: in the refracted shimmer-squares of a large disco ball, seven couples from BRB dance to one song each, and come together for a finale rendition of My Way. This structural simplicity allows for total emphasis on the movement. Every pair has their own nuance of style. The first song, Softly as I Leave You, is personified by the delicate softness of those dancing to it, figures in soft, dusty pink. It works really well as a contemporary piece on a ballet body. Their years of ballet training adds a weightless grace to the ballroom movements. I settle in, knowing I will enjoy the next half an hour.

At the crooning swell of Strangers in the Night fills the vertical heights of Sadler’s, a svelte pair in sultry dark blue tango across the horizon of the stage. They travel the dancefloor in confident diagonal directions, in suggestive diagonal angles to one another at the hip and shoulder. It is the intense passion of A Brief Encounter; the suspended bliss of the Shall We Dance? scene in The King and I. It is my granddad first dancing with my grandmother. Tharp has identified and caught the twinkling and romantic essence of the 1950s, and preserved it in a bell jar of dance for all to see.

Sentimentality turns into light comedy during the Somethin’ Stupid piece. Tharp understands Sinatra’s impassioned, long-sentenced appeals to be a show of male bravado, which I had never grasped until now. She choreographs her interpretation of the lyrics so clearly! The male character, who reminds me of a smitten teenager, shows off to his love interest with kicks so precisely on the beat that he must have been practising in his bedroom for weeks. The force of his love leads her with puppylike intensity, and he proudly shows us the woman that he ‘goes and spoils it all’ for. It is my favourite, a gem.

Towards the end, the red hot That’s Life duo showcases the whip speed legwork that BRB dancers are capable of. As the couple spicily spin to the end of the end, My Way replays for the last dance. We see all the pairs return, whirling in between each other, keeping to their nuanced style, each dancing in their way. The spectacle of pure dance is an apt ending image for ‘Nine Sinatra Songs,’ as we will remember just this: the couples, the colours, the songs and the passions. I think of American Graffiti — both are valuable crystallisations of an era, treasures to be shared between those who lived through it, and those who are young and curious.

Images: BRB press gallery.