Words by Bengi-Sue Sirin.

Taking my seat for Gregory Maqoma’s ‘Cion’, I am not sure what to expect. I have read through the programme that was emailed to all ticketholders (thank you Barbican — environment and budget-friendly!) and taken on board the two choreographic starting points: Maurice Ravel’s musical composition Bolero; and South African author Zakes Mda’s fictional character Toloki. Having googled Toloki, I know he’s a professional mourner. So I know the piece explores death. But I can only speculate on the format ‘Cion’ will be presented in; a linear narrative, like a story, or an accumulation of parts, like Ravel’s score? Dance often surprises me during a piece, but it is unusual for me to feel so in the dark before it begins.

We are kept in the literal dark for longer than we are used to. The only sensory stimulant is sound. Someone cries, in the unrestrained way unique to loss. As crying becomes sobbing, a dim and dispassionate central spotlight slowly illuminates the mourner, who is kneeling amongst graves marked by simple — but powerful — wooden crosses. We are watching a human being whose dignity has been razed by grief.

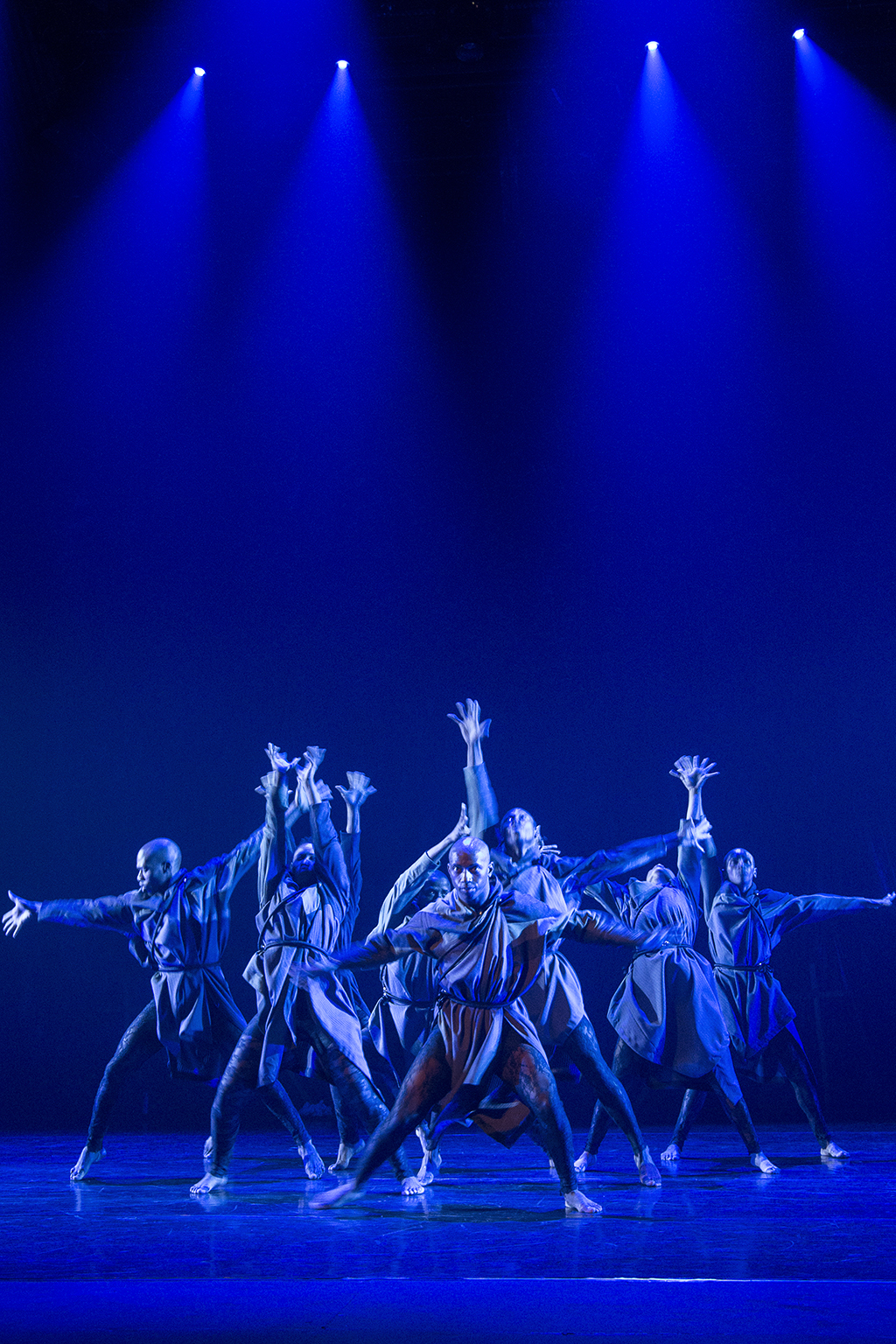

Fast forward to a groupwork section. Dancers are clumped together within an invisible parameter, tethered to the leadership of Gregory Maqoma’s Toloki. They move as one frenzied flurry, following Maqoma’s every reach with hyper-sensitive darts of movement. They gobble, cackle, and babble in phantasmic impulses. Such senselessness portrays these eight as ‘possessed by spirits,’ in keeping with the character description in the programme.

A little later comes a fragment of storyline, danced to Nhlanhla Mahlangu’s acapella quartet repeating ‘VOH MM-MMM.’ The protagonist is a woman, narrating the anguish, despair and frustration of bereavement by abandoning her body to swirls, sways, kicks, jerks, shudders and collapse. She removes her gloves (the same that the eight spirits wear) and hurls them at Toloki and his pack, defying any connection with them. Something about their presence maddens her; perhaps she feels they are to blame for the death, or that they impinge on the grieving process? Whether she likes it or not, the consistent ‘VOH MM-MMM’ rhythm contains the woman and these spirits together in one chapter. The difference is that rather than plot, we are served emotion. Maqoma makes desolation visceral, tangible.

Building like Bolero, the final section of ‘Cion’ throws more strands of death into the mix. We hear it in the dancers’ tap shoes, as even-rhythmed footwork evokes the hammering of nails into a coffin. We see it in the set and costumes, with a mountainous backdrop creeping right to the top of the high-ceilinged Barbican stage, rendering us at the bottom, in hellish depths; and bounty hunter black lace dresses and robes, with steampunk hats tilted like Liza Minelli in Cabaret. We feel it in the whirls of the yellow, tiger-striped lighting which encircles the dancers in a clump once again, no longer discordant, but harmonious. The choreography indicates that these spirits are at rest.

So, what of it? One thing is certain: reading ‘Cion’ in an ‘order’ confuses the point. Don’t seek a storyline just because it is inspired by a novel. This shift in how we think as an audience is something that Maqoma proposes in his TEDx talk. He insists that the stories that matter aren’t ‘Cinderella, Peter Pan or Snow White’ but real, human stories. Humanity, in all its unpredictability, its uncontainable dimensions of emotion, is not truthfully portrayed if compartmentalised in a Disney-like trajectory.

‘Cion’ is Maqoma’s polemic against reducing life to linearity, like a story timeline, with its beginning, middle and end. Think more of the act of building a jigsaw puzzle, where it comes together in random patches at a time. The piece’s success is in its entirety; the completeness of the jigsaw puzzle, once the final piece has been pushed in and you’re still comprehending the marvel of the picture while those around you are stood in ovation.

Images: Barbican Press.