Words by Katie Hagan.

The Bolshoi is back in town, beginning its three-week-takeover of the Royal Opera House with its epic thunderstorm of a ballet, Spartacus. Performed in London for the first time in nine years, Yuri Grigorovich’s original 1967 Soviet-inspired choreography has throughout the years seeped into the hearts of its spectators, as we follow the rise and fall of Spartacus’ eponymous, unwavering hero leading a mammoth slave revolt against the barbaric Roman Republic.

Generally known as ballet at its most absolute and bombastic best, on this occasion there were slight fissures in the performance that even Khachaturian’s soul-stirring, tectonic-plate-moving score could not remedy.

The first act was incredibly slow to start; the pirouette landings weren’t quite there — Alexander Volchkov’s Crassus in particular — and it generally felt as if the dancers just couldn’t keep pace with the music. At some points, the mood was so lethargic that even the drunken languor iconic in the Roman orgy scene seemed less of an audacious ‘damn-they’re-really-doing-it-on-stage’ and more of a continuation of the previous malaise. Oh dear. Â

Adding to this, it was unfortunate that Spartacus’ shackles broke just at the beginning. Although testament to Mikhail Lobukhin’s commitment and belief in his character, it did serve as an unfortunate metaphor for a performance which was stumbling even before it had begun.

The music carried the first half. The second and third acts however, came by some way of a miracle. And thank god when you’re sitting in a hot theatre. Not letting his broken shackles faze him, Lobukhin fused formidable strength, elegance and vulnerability, to present an admirably optimistic Spartacus jete-ing and barrel-turning his way to a freedom he will never taste.

His lover Phrygia, danced by the stunning Anna Nikulina, is bird-like at first and steadfast in her grief for the martyred Spartacus at the end. As a bird she breaks free from regimented ballet arms and her chaine turns are like the purest, freshest droplets of water. Her monologues are a welcome break from the thumping Soviet-propagandist choreography typified in Spartacus’ group pieces. Â

Aegina, the Courtesan, is the antithesis to Phrygia. She is the brains behind Crassus’s power pursuit and Spartacus’s undoing. Duplicitous and exhibitionist, you’re drawn to her like a moth to a flame and left spell-bound by her entwining arms and enviable back-bends.

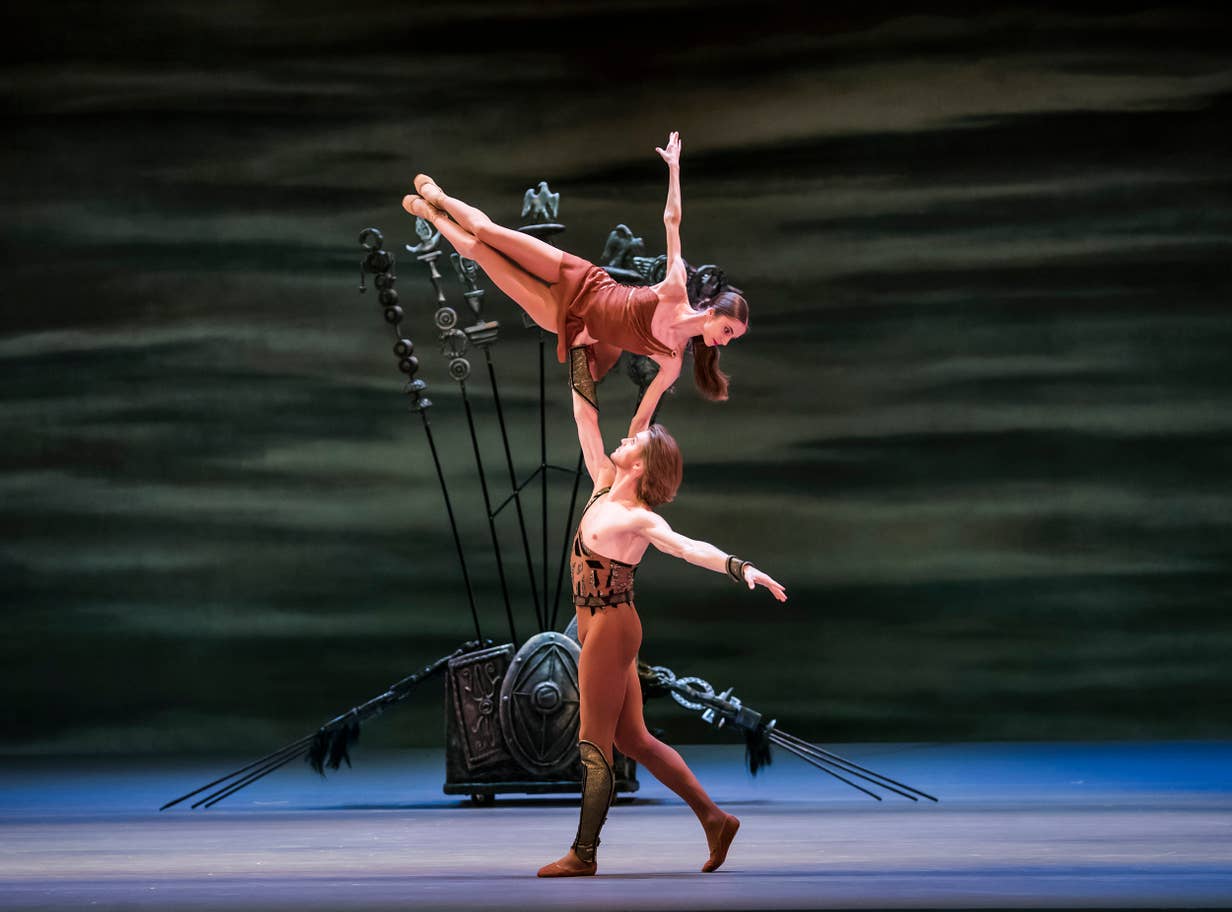

It must be said the ‘Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia’ is nigh on perfect. We get the mesmerising technique combined with the little jewel-like movement variations that Lobukhin and Nikulina can’t help but produce as the characters declare their love for one another. The lift in this pas de deux is arguably one of the most iconic in ballet; Nikulina slowly moving her leg until it sits bent in retiré, the violins finessing this moment. Watching Lobukhin lift her over his head, holding her with one arm as she emulates a diving swan is too much for the senses. I challenge anyone to identify anything more beautiful than that moment.

Although the choreography is slowly evolving into a tired armchair, Khachaturian’s majestic music and Phrygia and Spartacus’ adagio are the two reasons why we will continue to fall in love with this ballet for many years to come.

For more information on the Bolshoi Ballet’s productions at the ROH, see here: https://www.roh.org.uk/tickets-and-events

Image: Tristam Kenton.